According to the Meriam-Webster Dictionary, a “parasite” can be defined as follows: “a person who exploits the hospitality of the rich and earns welcome by flattery,” “an organism living in, with, or on another organism,” or “something that resembles a biological parasite in dependence on something else for existence or support without making a useful or adequate return”. Clearly the word “parasite” does not possess flattering descriptions. However, the protagonists in the film “Parasite” appropriately fit all three of these definitions except, when assigning the word “parasite” to a family of four struggling to survive economically in South Korea, this dreaded word loses its negative connotations. Instead, it invokes feelings of sympathy, bitterness and futility.

“Parasite” primarily follows Kim Ki-woo, a young man living with his parents and sister in a rundown apartment on the basement floor. The whole family struggles for work, so when Kim is given the opportunity to become an English tutor for a rich businessman’s daughter, he accepts it eagerly. Kim’s interactions with the rich family appear pure enough at the start, but through treacherous acts of manipulation, he manages to have the entire house-staff fired and replaced by members of his own family. Kim’s poor family aren’t exactly loveable rogues; their antics are understandable because the audience can visualize their unenviable living conditions, including one fitting piece of imagery where their house is gassed by toxins sprayed by government employees meant to exterminate the insects in the city. The rich family serves as the clueless hosts to our parasitic protagonists, but the script effectively does nothing to make them absurdly evil despite being the antagonists.

Yes, the prideful father of the household claims that lower-class workers have a particularly miasmic scent. But at the same time, he lovingly fathers his children and is adamant that anyone who is employed for him gets paid efficiently. The mother may be mind-numbingly naïve to the agitation she causes to all those around her, but whether she deserves to be tricked and schemed by the film’s protagonists is consistently murky. Essentially, the film establishes a grey area between right-and-wrong that is constantly present in the foreground of all the characters’ actions. Thus, watching the families clash both wittingly and unwittingly is as thought-provoking as it is tense.

The question posed by the film of the meaning of a “parasite” is what drives the film forward. The poor family would serve as the obvious solution, but the film does not answer this question with much certainty. Economic class differentiations aside, the poor family and the rich family in “Parasite” are almost perfect mirrors of themselves. They both have a married mother and father, an elder daughter and a younger son. Granted, one family is younger and wealthier, but in essence they are both alike. Thus, the question raised: why can one family afford a three-story house equipped with the latest technology and employed with several helping hands, while another is forced to fold pizza boxes to make rent? The poor family in “Parasite” may be sucking the money out of the rich, but hasn’t the rich family been doing the same thing on a larger scale?

Considering the emphasis the film places on how deprived most of the community surrounding the protagonist, one could argue that the upper-class families of South Korea, represented by the one rich family, are parasites taking the wealth from Korea for themselves and given nothing in return. This metaphor may not just apply to South Korea, but to the whole world. Perhaps my personal interpretation of the film’s themes are incorrect. However, anyone familiar with the mind behind “Parasite” would expect it to have a brutally honest social commentary woven subtly into a superb story regardless of its message.

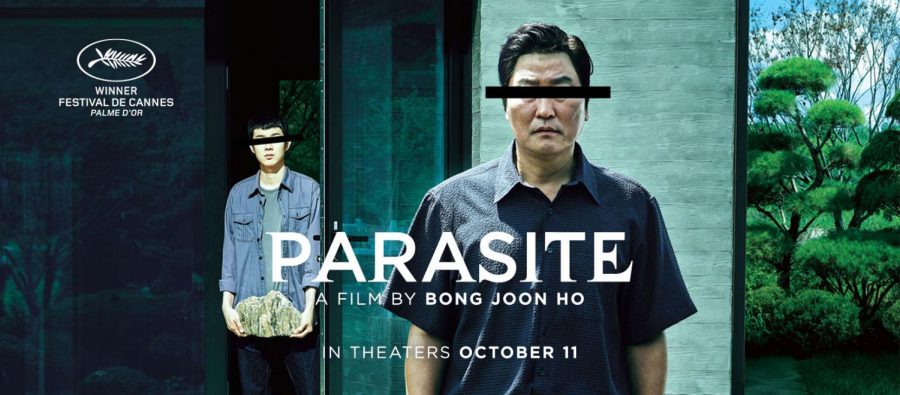

For anyone following the independent film scene, you have probably heard of Joon Ho Bong. Joon Ho Bong, the director and cowriter of “Parasite”, has a superb résumé of films, including: Memories of Murder, The Host, Mother, Snowpiercer and Okja. If you are a fan of South Korean cinema, you have likely seen the first three movies, as they have managed to break into the American film market. If you are a passionate film watcher who sticks to English-speaking films, or are just a casual indulger of Netflix, you have likely seen or scrolled by Snowpiercer and Okja. Along with other South Korean auteur Chan-wook Park, Bong has managed to make himself a need-to-know name in the heads of film fans. Considering their film credentials, the popularity of both filmmakers is rightly earned. Suffice to say, “Parasite” had a high bar to live up to. I can safely say it is one of Bong’s best films and, perhaps, it will be my favorite film of 2019.

Social commentary aside, “Parasite” is excellent as as it is tense, yet an oddly comical, home-invasion story with sympathetic protagonists. Although Bong does not seem to have a high opinion of the wealthy elite in South Korea, he is careful to portray the rich family as humans, meaning they are just as flawed and relatable as any real-life person. Despite the apparent dour message, “Parasite” could mark a positive turn for Korean cinema. “Parasite” is the first Korean film to win the Palm d’Or at the Cannes film festival, meaning it will certainly pick up further attention in the film world. My fingers are crossed for an Oscar nomination, but regardless of how many accolades this film receives, its message, as well as it serving as proof of the esteem of Korean cinema, deserves to be spread globally. Fans of all types of movies should put “Parasite” on their watchlist, and maybe come up with their own interpretation of Bong’s newest gem.

Matt Martella can be reached at [email protected]