Ever heard of The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse? It’s a story about a mouse from a town visiting his relative from the country. The country mouse is depicted as simple and humble, while the town mouse is used to a more luxurious, but often dangerous life. The story is clearly partial toward the country mouse, concluding the story with the aphorism “Poverty with security is better than plenty in the midst of fear and uncertainty,” but many would disagree with this story’s moral conclusion.

Take E.B. White, for example. He is best known for writing the popular 1952 novel “Charlotte’s Web,” but he also wrote a very influential article in the New Yorker called “Here is New York,” where he attempts to honor what he believes is the greatest city in the world. He praises New York for being a center of arts, finance, entertainment and religion. He also celebrates the peculiar way in which New York “blends the gift of privacy with excitement of participation” by “absorb[ing] almost anything that comes along.” In other words, you can participate in a variety of very interesting events happening all the time without being forced to participate in any of them.

While this may be an interesting topic for many, one may be wondering how such a seemingly unimportant debate could be relevant to any of the current problems our society faces. Despite seeming like a somewhat superficial topic, examining the way in which rural and urban communities influence the personalities and preferences of those who live in them allows us to gain a greater understanding of how these geographical sensibilities influence things such as political belief. This information is relevant particularly for the Democrats, since many within the party are torn on what voters want from the next president (radicalism or moderation). An understanding of the role of geography in American politics can help us better understand the beliefs and desires of different parts of the country.

Survey Shows Stark Divide Between Rural and Urban Areas

The Washington Post, in conjunction with the Kaiser Family Foundation, released a survey in 2017 that found a large cultural divide in the socio-political beliefs of rural and urban communities. About 70 percent of rural residents in the survey believed that they have different values than urban residents. Roughly 60 percent of rural residents believe that Christian values are under siege, while only a little over half of suburban residents and less than half of urban residents believe this to be true. 56 percent of rural Americans believe the federal government neglects rural areas in favor of cities. 42 percent of rural Americans also believe that immigrants are a burden on the country. Only 31 percent of suburban citizens and 16 percent of urban residents agree.

A lazy way of interpreting these phenomena, as many have done, is to dismiss these aspects of society as “a basket of deplorables,” as Hillary Clinton once remarked. Barack Obama said something similar, saying, “They get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.” The issue with these sorts of analyses is that they simply accept that rural citizens tend to be more prone to right-wing extremism as if they came from nowhere and are completely irrational. They fail to ask the broader question of why this demographic of people hold these belief systems and how they can be understood and addressed.

Many have rightly pointed out that the ascendancy of Donald Trump to the center of political discourse has exacerbated these extremist tendencies. The Washington Post notes that rural and small town voters supported President Trump by a 26 point margin while Mitt Romney was only able to win rural support by a 16 point margin in 2012.

Part of this growing divide between rural and urban areas can be attributed to economics. Rural areas have recovered far slower than urban ones since the Great Recession. Urban and suburban areas, for example, have had a net gain of 3 million jobs since pre-recession levels while rural areas have had a net loss of 128,000 jobs. About 60 percent of rural citizens believe there is less opportunity in their hometown and that greater opportunities could be found elsewhere. It is tempting to think that economic anxiety is the primary reason for the recent waves of far-right candidates like Donald Trump in light of this, but is important to note that rural residents who were more concerned about jobs within local their communities were actually more likely to vote for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election by 14 points. This is initially surprising when compared with all the statistics presented above, especially those that mention how rural residents tend to feel neglected by the federal government. One possible explanation of this is that the perception in a rural citizen’s mind of unequal treatment by the federal government has played a larger role in inflaming far-right tendencies than actual economic suffering. Regardless, it is clear that while economics play a key role in political beliefs they are not the primary cause of this divide.

Rural Areas Are Typically Conservative Throughout History and Around the World

This divide between city and country is not a strictly modern or American phenomenon. The tendency for more rural areas to be more conservative has been reflected in a number of other countries including Canada, Poland, Switzerland and Hungary. Rural areas in the U.S. have also typically been fairly conservative throughout American history, as a journal article from the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science notes. The article gives examples of how rural communities played a large role in supporting movements such as McCarthyism and the campaign of George Wallace, who was infamous for his support of segregation. One can also view the American Civil War in terms of rural and urban conflict, since it was a conflict between the industrialized North and rural South over conserving the institution of slavery.

Even in 19th century Russia, rural areas were more conservative. The peasants in Russia, according to historian Richard Pipes, were largely unaffected by many of the initiatives of the government and were still entrenched in old Muscovite traditions, which is important since leaders such as Peter the Great and Catherine the Great had sought to forcefully Westernize society and remove most of the old Muscovite traditions from mainstream culture.

All of this shows that while a great deal of external factors can affect one’s belief system (such as religion, family, culture or class), where one lives can have a significant effect on how one views the world. When you live in a rural community, you can be, to some degree, isolated from society. This means that your conversations and interactions are generally limited to a select group of people who probably also live in your community. The most important things in your life are often within your community and you have no need to leave except for special circumstances. Problems within the community will often be fixed by the community barring special circumstances where there are fewer places nearby with enough resources that could provide aid. Since everything within a small community is geared towards the maintenance of the community, you are more likely to adopt a conservative mindset because conservation and maintenance have dominated your community’s discourse.

In more urban areas, however, the circumstances are different. There is a wealth of resources in cities. They, unlike rural communities, are constantly changing and growing. If you live in a very urban area, you are in an area of constant economic and cultural output. The larger populations of cities along with the various economic opportunities means that there is a great deal of diversity within a city. It also means that there is only a limited degree of community because you can never know everyone within a city. There are often various small communities within the large community of the city. For this reason, cities are more pluralistic by nature, since it involves several different communities competing and working with each other.

These definitions are by no means perfect and do not fit all scenarios. The qualities of urbanity and rurality exist on opposite sides of a spectrum, and thus where one area falls on this spectrum determines the extent to which these definitions can be applied. The importance of having these definitions is to better understand the mindsets of people from different regional backgrounds.

These definitions should also be viewed with the dawn of the internet in mind. The internet and the wide availability of technology even in rural areas to some degree has decreased the amount of isolation from society rural residents face. Granted, there has been a good deal of research on how rural residents consistently lack the same amount of technological availability more suburban and urban residents have and are, therefore, still somewhat isolated. Even with technology geographical isolation can still play a crucial role in one’s mindset.

Geography’s Centrality in the American Political System

A myriad of other factors such as religion, social class, family background, age, gender, the proliferation of fake news and more can also affect an individual’s political beliefs, but the influence geography has on politics is particularly important in the American political system.

The federal government represents states, not individuals. The original way elections were conducted in most states was that people would directly elect members of the House of Representatives, senators were voted for by state legislatures and the president was decided by electors appointed by the state legislature, not the popular will. Individual citizens only had direct say in the House of Representatives in these first systems.

Reforms have made it so that senators are elected directly and that the electors from each state all vote for the candidate who wins the popular vote within the state, though Maine and Nebraska are exceptions. These reforms have decreased the amount states are represented and increased the amount individuals are represented. States are still very much represented in the federal government.

According to Emily Badger of the New York Times, states containing about 17 percent of the national population could theoretically form a majority in the Senate. This is because states that have smaller populations are advantaged in the Senate since every state is given two representatives. Thus, states that are more rural are given an advantage in the federal government.

The election of the president is a little more representative of individuals than the senate since the number of electors is equal to the number of seats the state occupies in both houses of Congress, but states are represented through the winner-take-all system in every state (except for Maine and Nebraska) awards their electors to the candidate who wins the majority in the state. This system benefits the states over individuals within them because it makes the majority opinions of individual states the deciding factor rather than the direct majority opinion of individual citizens. This can change the results of a presidential election when the majority of citizens nationwide support one candidate, but the other candidate is able to obtain a few slim majorities in a few states that allows for his or her victory.

What this all illustrates is how the U.S. electoral system is designed in a way that represents both individual citizens and regional interests. The representation of states in elections to federal offices is meant to be a safeguard against the majority exercising its power over a regional minority and ignoring a regional minority’s needs. What this means is that rural states are given an advantage since they are a regional minority due to their population size.

There is a limit to which geography can explain our current political situation. I spoke with Professor Daniel Gordon of the department of history at the University of Massachusetts about the nature of political polarization in our society. One thing he notes is that since roughly 80 percent of the population lives in urban communities, there’s no way geography can explain all of America’s political polarization.

This is best seen by the state of Vermont, which is the second most rural state in the union. Unlike most rural states, however, Vermont is typically a state controlled by Democrats. Clearly, other factors are at work.

One factor Gordon mentions for political polarization is a global trend in Western progressive thought that, he argues, has become unacceptable to anyone who prioritizes religion, nation, and/or tradition. He also argued that the root cause of polarization was that divisive ideologies built on hatred and anger have gained popularity as a way of creating meaning from our political situation. Political parties, according to Gordon, use and encourage this polarization for their political gain.

These thoughts on political polarization help place the geographical factors that influence elections into context. The fact that political parties are exploiting a tendency in the electorate to support more polarizing and hateful ideas helps explain to some degree why the rural-urban divide has worsened in recent years.

People in rural areas live in environments that make it more likely for them to support more conservative ideas. The idea that progressive philosophy has progressed too far left for those who value nation, tradition, and religion to accept is also important because the values of nation, tradition, and religion are all conservative values in our increasingly cosmopolitan and secular society. This means that people from rural areas are far more likely to be persuaded by and support these extreme and polarizing views that have gained popularity because the fundamental values that motivate them (tradition, religion or nation) are already encouraged in rural areas.

The Rural-Urban Divide and the 2020 Election

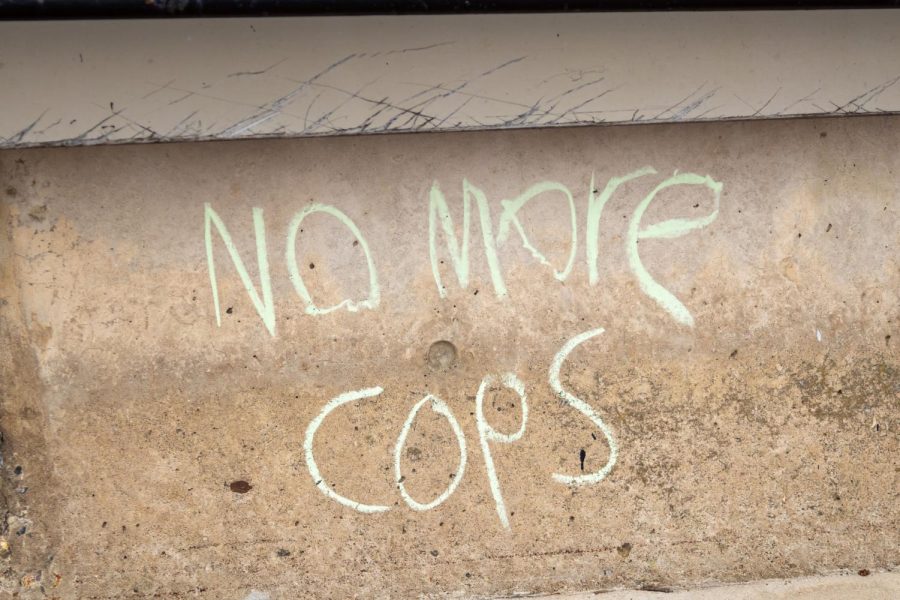

President Trump and his political allies seem to have a keen understanding of this. Rhetoric from President Trump, as the Washington Post notes, shows a clear intention to highlight the political division between rural and urban communities in order to strengthen his support from rural residents. The response from mainstream Democrats has been to become even more progressive. Candidates like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have staged campaigns promising massive reforms that could change several areas of society in significant ways.

While radical overhauls may have positive effects if implemented, trying to sway undecided voters with proposals that subvert conservative values will only ensure that those reforms never take place. Considering the 2016 election, Democrats should have no reason to believe enough citizens are ready and willing to support extremely progressive reforms. What Democrats should attempt is to make more conservative appeals in order to sway voters who may not necessarily support Democratic values but dislike the far-right values that are espoused by republicans. A far-left Democratic platform will likely risk alienating voters in this category. Democrats should stop worrying about trying to energize their base against Donald Trump, the opposite of a far-left candidate.

We cannot fail to realize how central the debate of “Town Mouse and Country Mouse” is to our contemporary political discourse. The divide between rural and urban areas is, if anything, growing, and the growth of this division will result in greater political division as well. We must learn to reconcile these exacerbated differences by understanding these differences and finding areas of agreement. The strategy of both political parties has been much less of an honest attempt to understand the other side, but rather a war that consists of competitors trying to recruit new members to subdue the other side, much like mice fighting for cheese upon a mouse trap.

Benjamin Schnurr is a Collegian contributor and can be reached at [email protected].

Ed Cutting, EdD • Jan 29, 2020 at 11:37 am

The important thing to remember is that the Populist Movement of the late 1800s (not to be confused with the Progressive Movement) is that it evolved out of the Granger Movement — which evolved out of the local Granges, a fraternal organization for farmers.

.

The “Free Silver” (pro-inflation) movement and the rest were all inherently rural movements — the farmers wanted inflation to reduce the amount they owed the urban (Eastern) bankers. So the model of the rural areas being reactionary has not (and is not) always true.