On June 2, 2020, if you went on Instagram expecting a barrage of saturated pictures, you would instead see your feed flooded with a single color: black.

The social media movement #BlackoutTuesday began as a protest following the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and countless others. A tweet from @pausetheshow announced June 2 as a “day to take a beat for an honest, reflective and productive conversation about what actions we need to collectively take to support the black community.” Two Black music executives at Atlantic Records, Brianna Agyemang and Jamila Thomas, started the initiative together. Their campaign, although well-intentioned, quickly devolved into another meaningless trend — #BlackoutTuesday diminished an authentic response to thousands of meaningless black squares.

The posts developed controversy when they started clogging hashtags that had important, relevant information about the Black Lives Matter movement. Many of the posts were captioned with some variation of #BlackLivesMatter and nothing else. I was unaware of the trend at first and it astounded me as I scrolled through post after post of black screens with little to no descriptions. When I searched the hashtag, which before was flooded with information about the ongoing movement, I found nothing but an abyss of black squares. The trend, trying to draw media attention to Black Lives Matter, expunged the hashtag of useful and purposeful information.

In this way, June 2 began another movement: one of white people trying to mark themselves as anti-racist. Daring to not post the holy grail of Black allyship — the black square — was met with judgement and outrage. I didn’t post it for the reasons outlined above and was messaged by my friends who were angered that I wasn’t “doing my part.” The criticism surrounding what we do and don’t post on social media shaded the once-innocent black square in a darker tone: it had become a symbol of white fear and guilt.

The Black Lives Matter movement awoke an unidentified fear in white progressives across the nation, examined and named by author Robin DiAngelo as “white fragility.” DiAngelo, a racial equity trainer and academic, titled her novel after this collective anxiety. She debunks the idea that racism is an act and establishes it as a system we are all complicit in. White progressives are terrified of being accused of racism because they define a racist as a person who is outwardly prejudiced against people of color. By partaking in activism online, they feel morally superior and evolved from such behavior and want to make that clear to everyone around them. As DiAngelo says in her book, “White progressives can be the most difficult for people of color because, to the degree that we think we have arrived, we will put our energy into making sure that others see us having arrived.” By rejecting that we are all implicitly racist, there is no room for change or reform. They hold the system of racism in place with their own smug thumb.

I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge that performative social media activism has been the stepping-stone for some real, groundbreaking activism. Media’s fixation on racism has been enough to make corporations start to sweat. Following the #MeToo movement, businesses that did not fire sexual predators or make policy changes began to crumble. The same infrastructure shift was expected from the Black Lives Matter movement. Although media activism on the individual level was largely performative, it serves as a watchdog for racist behavior and disrupts the visible patterns of white solidarity.

While social media trends peaked, so did the COVID-19 pandemic within the United States. Americans confined to their homes took to social media. Instagram had a dramatic uptick in posts and stories. People were beginning to experience COVID-19 fatigue after months of isolation drained them of motivation to do their part to contain the virus. In March, Americans were energized to do whatever it took to end the pandemic quickly. Months dragged on with no end in sight and people were largely desensitized to COVID-19 news by June. There was a collective desire to have something new to focus their energy and thoughts on. The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement online provided an easy outlet.

The resurgence of the BLM movement signaled a shift in media attention from the individual to social issues at large. Instagram had a reputation for the superficial; a platform for people to flaunt the best parts of their lives. Did the change from selfies to BLM awareness posts make it more genuine? I think not. Social media is a place for people to market themselves as attractive or desirable to others. The marketing angle is now geared to promote the social issues they want others to know they believe in. Activism posts are less about raising awareness of the issue and more for calling the user’s stance into attention. In essence, the BLM posts that went viral last summer were often reduced to a dog whistle, a way of letting one’s followers know that they are anti-racist and have progressive values.

For white people, activism has become “trendy,” which calls the motive into question. Are they doing it because they feel strongly about the issue or to follow social media trends? If posting about BLM makes them trendy, then by doing so they can market themselves as desirable and fulfill the unspoken goal of social media. This paradox explains why the change in media content doesn’t mark a change in the ultimate objective. The end goal for many is still to gain followers or be seen as popular and attractive, and posting about BLM is simply a means of getting there.

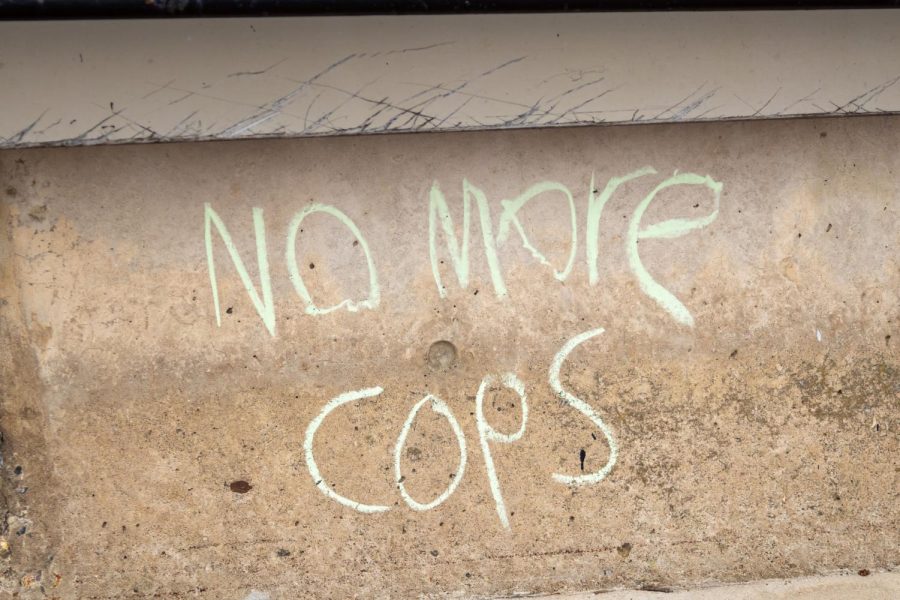

In a desperate plea to be a good white person doing their part, social media is teeming with a constant stream of posts and stories from progressives. Chain stories like “tag 10 people who won’t break the Black Lives Matter chain” are evidence of white fragility thinly veiled as Black allyship. The trends that were littering social media in the wake of George Floyd’s death accomplished little more than giving white people self-pride for being woke. Black squares and chain mail are not enough.

Now that it is Black History month, we are once again faced with an opportunity to use our platforms responsibly. We can do so by promoting and donating to causes that will support black communities. First, there are a host of GoFundMe pages for the families of police brutality victims. Here are some victim’s families to aid: Walter Wallace Jr., Kevin Peterson Jr., Jacob Blake, Elijah McClain, Rayshard Brooks, James Scurlock, Tony Mcdade, David McAtee, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Daniel Prude. Another worthy cause is The Bail Project or National Bail Out, which are nonprofit organizations that pay the bail to free protesters arrested during BLM rallies or marches. You can also search for more localized bail funds to aid a city near you. Megafunds are another great way to donate; each fund given to Act Blue is split between multiple racial justice organizations and you have the ability to adjust exactly where your donation is going. There are hundreds of organizations out there, so go promote, volunteer and donate to one that speaks to you.

We can also use social media as a platform to educate and inform of the hardships Black communities face on the daily. We, as a white collective, must use our position of privilege to be a voice for the voiceless. Activism must come from a place of compassion, not performance. Going along with trends like the black square furthers our complicity in white solidarity. By doing so, we are blowing the anti-racist dog whistle and removing ourselves from the need to keep working on our own racist patterns. We must use social media to amplify Black voices rather than drown them out in a sea of white allyship.

Olivia dePunte can be reached at [email protected].