Pat Griffin recalls the struggles she faced as an LGBTQ+ athlete, struggles that fueled a fire inside of her and became a lifelong devotion to advocacy.

“We were all scared, and we all hid from each other,” Griffin said.

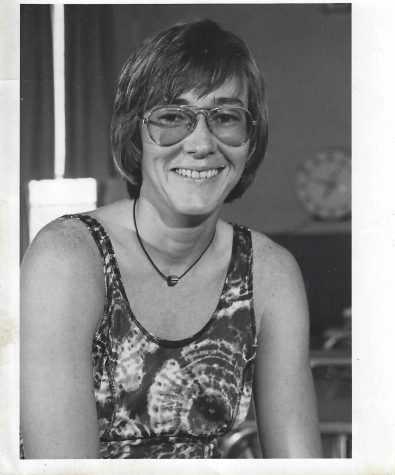

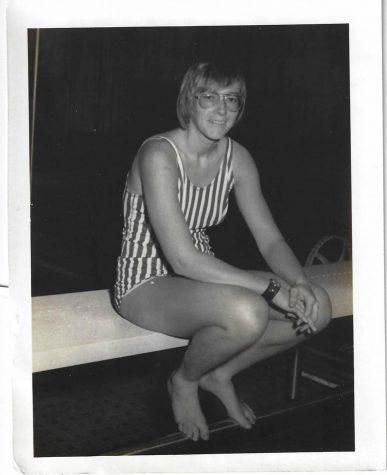

Griffin arrived in Northampton in 1971, when she was hired as the Massachusetts swim and dive coach. Within the facilities of the UMass Amherst campus, Griffin began to find comfort in her new surroundings, even though, at the time, just a select few knew details about her sexuality. As the area began to provide warmth and acceptance, the list of friends and family who knew about Griffin’s sexuality expanded and the environment brought out a newfound trust in living the true Pat Griffin lifestyle.

“I would go dancing or go to LGBTQ+ events, and I would see other athletes there,” Griffin said. “They started coming to me to talk, and I was horrified to realize that for their generation of athletes it was not all that much different from mine … that’s what made me want to be a pioneer. That is what made me want to do something to be a part of changing that for future generations of athletes.”

In talking with those athletes, Griffin quickly found herself at the forefront of a much larger movement. Shortly after, she began establishing connections with lesbians in the conflict center at UMass that were willing to help LGBTQ+ athletes deal with the struggles they faced.

After five years coaching, Griffin transitioned into a professor role at UMass. She began attending more workshops for women in sports and noticed a trend in them: no workshop or convention was talking seriously about the issues in LGBTQ+ athletics. She slowly began to change that.

As soon as she became a speaker in workshops and on panels, Griffin integrated some of her own issues with women’s sports into the conversation. She remembered how alone she felt as a closeted athlete and wanted to give women the guidance and resources she never had.

Griffin charged forward on her mission to change the sports world, but as she pushed herself into advocacy, she was simultaneously pushing herself further and further out of the closet. She knew that coming out would soon be necessary, not only for herself, but for every other athlete hiding their true identity.

In 1987, Griffin prepared to speak on a panel about homophobia in college sports with a few colleagues — including her doctoral student Sherry Woods, who was also lesbian. Similar to Griffin, Woods was very comfortable in her own skin, but hadn’t come out publicly yet. The two decided that they would each speak publicly about their sexuality for the first time during their presentations.

Deciding to come out was just step one of the process. The much more difficult part was the meticulous planning of exactly when and how to do it. Although, one thought that made the process a little easier for Griffin was knowing that there wouldn’t be many people at her session. Or at least, that’s what she thought.

Even having the last time slot of the last day — a recipe for low attendance with people trying to head home early — the room was filled to its capacity. Griffin and her colleagues were bringing up uncomfortable issues that hadn’t been discussed at the convention before, and it was clear people wanted to listen.

“There were a lot of lesbians who were afraid to come, because they thought coming into the room would out them,” Griffin said. “And there were others just cheering for us because they were so glad that someone was breaking the silence.”

When Griffin and Woods looked out at the crowd, all they saw were comforting faces. There were lots of women just like them in the audience, the people they wanted to do this for in the first place. Those comforting faces quickly turned into welcome applause when years of hiding came to an end and hours of planning turned into perfect execution of some of the most important sentences Griffin and Sherry would ever speak.

A lot of emotions surrounded that presentation: relief, excitement, elation. But Griffin’s fondest memory of the event was the brief interaction she had with Walter Kroll, a fellow professor at UMass at the time.

“He didn’t say anything to me, but he stuffed a little piece of paper in my jacket pocket and walked away,” Griffin said. “When everybody finally left, I opened the paper and he just wrote, ‘I have never been prouder to be a member of the UMass family’.”

Kroll has since passed away, but Griffin never let go of that piece of paper. It remains in her office at home, a heartfelt reminder of a beloved colleague and supporter of Griffin’s.

Coming out was the last internal barrier Griffin faced, and by breaking it down she blew open the door to make an even greater impact as a voice for the growing movement that she created.

Three years after the convention Griffin went to Vancouver to compete in her first Gay Games. She won a bronze medal in triathlon that year and went on to win gold in hammer throw eight years later, but those achievements were nothing compared to the feeling Griffin got from competing without fear.

“I remember walking into that stadium, it just gave me chills, because I realized that it was the first time that I ever competed as an athlete fully owning who I was,” Griffin said. “Lesbian athlete, it was the first time I had ever done that. And it was a great experience.”

As a closeted college athlete, the mental toll it took to hide her identity from the world for so long was incalculable. She felt voiceless, but eventually she became the voice. Competing in the Gay Games showed Griffin that she could be herself on the field and be proud of it.

Having so many different experiences as a lesbian athlete and advocate including the Gay Games, Griffin wanted to tell her story on a bigger platform.

She took her personal experiences, combined them with testimony from other LGBTQ+ people in athletics, and wrote a book about them.

“It was a work of total passion for me,” Griffin said of her book, “Strong Women, Deep Closets: Lesbians and Homophobia in Sport.” “There wasn’t a book like that before I wrote it, and I wanted to be the one to write it and I wanted it to be able to amplify the voices of athletes and coaches.”

In 2017, Griffin received the Honor Award from Women Leaders in College Sports for the tremendous impact she made on LGBTQ+ athletics. That award in itself showed just how far Griffin’s advocacy had come.

“I can remember doing a workshop in 1990 in Washington D.C. for that organization, and my being on the program was so controversial that there were actually women athletic directors who wouldn’t come to the conference,” Griffin said of her first experience with the organization that eventually became the Women Leaders in College Sports. “And to come full circle and to get that national award from them, it was just great.”

Colin McCarthy can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @colinmccarth_DC.

Mary Elstein Wood • Jul 3, 2021 at 11:27 am

Pat you are an inspiration, and a great role model. I recall our days together, with fondness at Northwood High School.

You have definitely made an impact on so many lives. I am extremely proud of you.

Maureen Novak • Jul 3, 2021 at 10:47 am

A favorite Classmate of all at Northwood High School Class of 1963. Congratulations Pat Griffin.

Linda Scott • Jun 30, 2021 at 10:51 pm

Pat Griffin is a full fledged she-ro and has been an amazing supporter of LGBTQ+ students and athletes. Umass was lucky to have had here there.

Dave Griffin • Jun 30, 2021 at 12:03 pm

Love my sister and the changes and leadership she has created over the years. When she first came out to me years ago, it was like, come on Pat, you think I didn’t know? Looking forward to seeing her later this year!