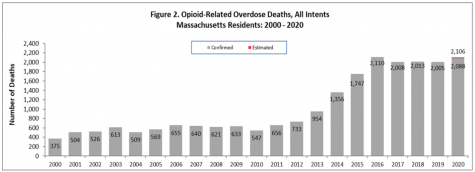

While the country grappled with the coronavirus pandemic, an existing public health crisis worsened across the Commonwealth.

A larger number of Massachusetts residents died from opioid-related overdoses in the first nine months of 2021, compared to the same period in 2020, according to preliminary data from state health officials. Opioid-related overdose deaths in the state also increased by 5 percent from 2019 to 2020.

Across Massachusetts, the numbers vary drastically by county. Middlesex, which is also the most populous county in the state, has the highest number of opioid-related overdose deaths. In Western Massachusetts specifically, Hampden county bears the burden of the most deaths. Springfield and Holyoke, two areas of concern in the county, saw the number of opioid-related overdose deaths double from 2016 to 2020.

No single factor can be blamed for the increase in opioid-related overdoses. Rather, experts in the Western Massachusetts recovery community say it was a combination of various conditions, including newfound isolation, tainted drug supply and inability to access care.

Michele Farry, regional development manager of the Drug Addiction and Recovery Team and Health Information Exchange, said her team noticed the impacts of COVID-19 restrictions almost immediately.

“As transportation and our larger infrastructure systems began to be impacted, so did treatment systems. So did behavioral health agencies, so did recovery coaching organizations and harm reduction organizations,” she explained. Lockdown and isolation only made things worse.

“One of the things that we know in working with people with substance use is isolation is a very, very high trigger for relapse recurrence,” Farry said.

The combination of isolation and stress caused by the uncertainty of the pandemic drove people to relapse, said Detective Joseph Emiterio of the Holyoke Police Department. In his work with community residents at the Department’s Narcotics Intervention Bureau, he found that the pandemic only “made drugs more readily available.”

“There’s a few different factors involved that are attributed to the amount of overdoses. One is drug supply. How are those specific drugs mixed, is it a more potent batch, things of that nature,” he explained.

Detective Dorothy Beben found that job insecurity and uncertainty may have played a role in drug use during the pandemic. “When businesses closed down, people didn’t have that time to stay busy. From what I’ve heard, that’s caused people to relapse during that time,” she said.

People with established “safe space” social networks for drug use found themselves using in unfamiliar settings and “accessing their substances from unknown distribution channels,” Farry said. Unfortunately, this meant increased risk for fentanyl exposure.

“Even people that I know [who are] very, very close to me were going out on the streets trying to find a drug dealer,” Mark Jachym, a recovery coach in Springfield, said. They would go out in search of the drugs they usually used, such as percocet, oxycontin and vicodin.

“A very high amount of those street drugs that people thought were actual percocet, et cetera, were not. They were fentanyl, they were cut with all kinds of things. People thought they were taking something they were not,” Jachym said.

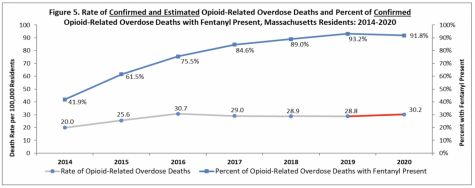

Fentanyl, an incredibly potent synthetic opioid, was present in 92 percent of opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts in 2020. According to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, which cited the Drug Enforcement Administration’s 2015 investigative reporting, “much” of the fentanyl in the state is illegally made rather than pharmaceutically.

“Our drug supply is contaminated, we do not know what anything is anymore,” Farry said. “It’s very, very unfortunate, but fentanyl is in everything.”

“The pandemic [made] life more stressful for people who lost their jobs, for people who had kind of lower food security, for people who are unable to support their families,” Peter Ciurczak, senior research associate at Boston Indicators, said.“Those are the kinds of factors that push people into using. Its fentanyl that can ultimately cause their death.”

While individuals struggling with opioid addictions found themselves in increasingly worsening situations, those in the recovery and harm reduction community encountered barriers in trying to help them. Farry recalled the initial waiting game that occurred within systems of care in early 2020.

“There were no in person meetings that were happening. There were limitations on detox and treatment beds available, and everyone was learning as they went,” she recalled.

Even emergency rooms became inaccessible for a period of time.

“I’ve had people come to me and tell me that they weren’t even accepted because it wasn’t COVID and they needed to monitor how many people were in the hospital or in the emergency room,” Jachym said.

Treatment facilities, which were already limited in their availability, became even harder to land, and Jachym found himself struggling to secure beds for people looking to detox. Treatment centers turned away people looking for help, citing concerns over the spread of COVID-19.

“I wanted to try a place in Berkshire County that had an available bed,” Jachym said. “Once they found out that the individual was from Hampden County or the Springfield area, they said, ‘nope, can’t take them, don’t want them because they’re not from around here. And we don’t want to be taking people from outside of our area, because we don’t know where they’ve been.’”

Wanting to detox is an enormous step for someone to take, Emiterio said. When someone reaches out to the Narcotics Intervention Bureau for help, time is of the essence.

“If there is a bed available, we might not be able to get someone there for hours at a time,” he said. “In that gap, we lose the individual at times, they don’t want to wait around, or they change their mind pretty quickly.”

To make matters more difficult, transportation to treatment centers – an issue even before the pandemic – became harder to secure.

“A huge majority of people we deal with are homeless. They’re not from town, or they may have burned all their bridges with family members,” Beben explained. Getting them a ride to treatment facilities can take even longer, further drawing out the time it takes to get them in a detox bed.

Homeless individuals were further isolated from treatment due to the lack of in-person recovery options available. From therapists to outpatient intensive care, receiving help for substance abuse went virtual.

“In Hampshire County, there’s a lot of issues around Wi-Fi and cell phone access. So even if you could have a telehealth appointment, you needed to have a cell phone with a plan and be able to get online,” Farry said.

Even at treatment centers that were accepting patients in-person, the quality of care at the height of the pandemic was not successful for everyone.

“You would stay in your room, whether you had a roommate or not, and the groups that they would do would be via Zoom on your phone,” Jachym said. “So even though you were in-patient, you still weren’t meeting someone face to face. And that didn’t work very well for a lot of folks either.”

On the other end of these Zoom calls, recovery coaches were grappling with providing care virtually.

“Many of the people that were part of our outreach program – recovery coaches – were not technology savvy and had a very strongly held belief from former recovery models that in person meetings are the most effective way to meet and assess a person,” Farry said.

After getting over the learning curve of providing telehealth, the coaches grew to embrace technology “as a multiple pathway of connected connectivity to people in general,” she recalled, a technique that will allow for various kinds of recovery assistance moving forward.

“Some of us prefer to be in a larger social setting to receive our support, and some of us prefer to do that one on one,” Farry said. “Having that opportunity now as another tool in our toolkit is one of those things that we took from COVID and will continue to use as another avenue to meet people where they’re at.”

Sara Abdelouahed can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @AbdelouahedSara.