There’s anticipation encircling the room. It’s not loud, but not quiet either. People seem to be focused on bustling around the corners of the room to find a worthy view. A subtle buzz of wonder warms the space in between conversations. Maybe for what they know will be experienced or maybe from the amped energy of the album they probably listened to on the way here. Though not on the stage yet, Ryan Beatty has already infused the venue.

The ambience of the southwestern desert, captured in Beatty’s third studio album “Calico,” filters through the room, manifesting an airy composure. As “Seeds and Stems (Again)” by Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen plays overhead, the lights fade into darkness. A single white light appears, and from the beam of light, the sound of melodic piano keys.

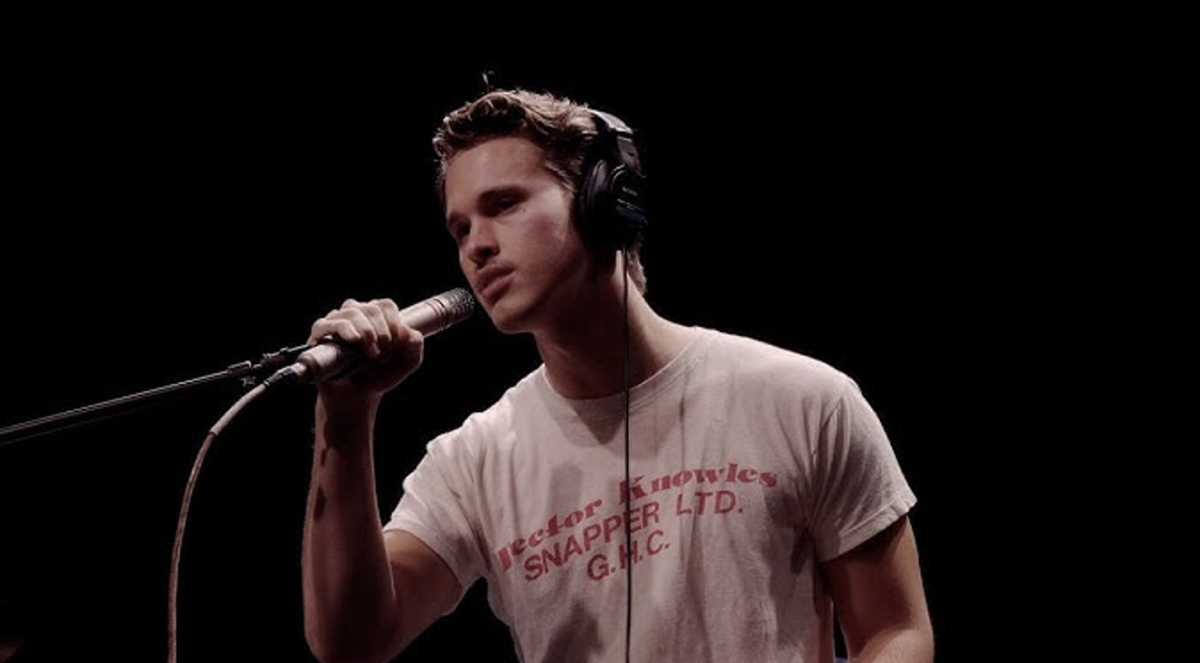

To start the show, Beatty’s pianist begins to play an extended piano opening to “Ribbons.” Five more members of Beatty’s band enter the stage, taking their respective places. The wistful piano tapers into the metered keys of “Ribbons.” Amid the instrumental transition, Ryan Beatty strides onto the stage. With a discreet appearance, his position at the center of the stage doesn’t seek attention.

The band continues playing at a softer tempo in the background; Beatty addresses the crowd after the first song. He thanks the audience for coming to “celebrate a record that means so much to me; I can feel the spirit in this room.” He’s right about the audience. The people around are held up in the melodies of the arrangements specifically constructed for a live show. The empathic nature of Beatty’s vocals reverberate through the audience, which is more than receptive to the artist in front of them – the people posed in a devoted reverence.

“Calico” was a turn in Beatty’s discography. Always a lyricist aiming for emotive vocals, “Calico” was a body of work that brought Beatty inward. He challenged himself to craft an introspection that spilled into a cinematic story of self, love, hometown and the indiscernible search for meanings that can be found after the failure to find them. These aspects came together into a visceral amalgamation of emotions, vignettes and rhythms in Beatty’s image.

The visceral relationship with deep-seeded emotions are the guiding forces of the night. Belting “Bruises Off the Peach,” Beatty’s vocal pitch searches for something between the patchworked thoughts assorted through in his lyrics. Like Judee Sill in her song “Jesus Was a Cross Maker,” which played before Beatty’s set, Beatty’s lyrics are unconcerned if his thoughts zigzag between lyrical moments, because his vocals are entranced with reaching a catharsis that is no longer out of grasp.

As the band transitions into “Cinnamon Bread,” their instruments louden, and Beatty’s vocals clarify. The band’s volume rises to meet the vocals’ need to be heard. Not clashing, the band and Beatty are harmonizing. This partnership is a focal point of the night’s show. Often the band of a solo artist can seem to be accompanying acts regulated to the background of the singer’s shine. But tonight the band is a co-author to Beatty’s performance.

Stripped-down instrumentation was essential to the making of “Calico.” On the album, the production of instruments inform the storytelling with gradient movements that encode the lyrical vignettes. Live, the instruments are heightened to retrace the emotional core of “Calico” to a new meaning. When Beatty isn’t singing, the instruments are. They are as much a chorus as Beatty’s melodic voice is.

For “Andromeda,” the band’s playing becomes a production performance. At the chorus of the song, the instruments slow to a stop and Beatty’s singing becomes the center point. But, for the second iteration of the chorus, the band builds up, escalating the impassioned lyrics. The drum is heavier with each beat leading the climb to the outro. There, Beatty takes a turn and augments his voice with a vocal effect, clasping the climax of emotional tension into feathered feelings.

Throughout the show he’d been sitting down, now standing to deliver “Bright Red.” In standing, it’s highlighted how Beatty hasn’t been simply singing the songs of his album, he’s been performing them. Though sitting for most of the show, his emphatic nodding, a physical response to the music, shows a thorough engagement.

A jazzy, groovy arrangement to “Haircut” matches the rainy, cold night in Boston. The song feels reconstructed to illustrate a new musical environment meant to bring listeners closer to Beatty’s world. He covers “Cupid,” the next song in the setlist arc revisiting his older music. Beatty riffs some runs over the piano. “Powerslide” is given a new tone, turning it into a downcast reminiscence of a long-gone summer. The taps of the drum recreate the wind-down of a summer day.

The band’s instrumentation brings to life the emotional environment of the singer on “Backseat,” with the drums sounding like falling rain and the guitar evoking pages turning. On “Casino,” an acoustic sound weaves into the amplified production. The instruments layer over each other with each verse of the song, like they would in a production deck, allowing each instrument to have its moment.

Beatty returns to “Calico” with the illusory “Hunter.” The song is a fantastical dream recounted.

Sonic landscapes continue to be cultivated with hazy intertwines of the piano. At the end of the song, a single light illuminates the piano. The piano has been a centerpiece of the night, anchoring the core of the song’s performance. In this piano piece, the production vision for a “Calico” live show blooms. Seamlessly, the pianist goes from their individual arrangement into the beginnings of “Multiple Endings.” The song’s second verse brings together the rest of the band with the pianist, the piano no longer the sole narrator, and the song’s imagery magnified with the synthesis of more instruments.

“White Teeth,” a song of catharsis made up of reflective moments, is performed without remorse. Beatty captures the feeling of acceptance of things that cannot be changed. After this song comes a speech. And then Beatty leaves us with the band, a beautiful conclusion to the night. And it would have been, as the band finishes playing, and his towering shadow is gone. But soon his figure reappears and the band plays on.

Dolly Parton’s “Do I Ever Cross Your Mind” is re-imagined in Beatty’s mournful voice. He sings into the void where a person once was. Less of Parton’s wondering, and more of the dreadful hoping. Ryan Beatty begins his official goodbyes to the night with “Little Faith.” This time he exits, not returning to the stage. In his absence, the band elevates. What has been left is everything that Beatty sought to create with “Calico.” He’s an artist that builds upon his work, improving his lyricism to resonate deeper with emotions that seem to evade verbalization.

Nothing is left unsaid with Beatty’s performance. In conjunction with his band, “Calico” is fully expressed, even beyond its original recording. The musical arrangements of the night were carefully crafted to emphasize the visceral scenes first brought to a recording studio. Live, Beatty guides the audience through moments and recollections as they happened, unafraid to hold back. He wants to feel the lyrics and allows them to flow through the intricate instrumentation of his band, handing what they create to the audience to hold however they can. The show ends where it started. A single white light beaming from a darkness now devoid of heaviness.

Suzanne Bagia can be reached at [email protected].