September’s cover story in The Atlantic, titled, “The Coddling of the American Mind,” made every logical misstep in the process of redefining a trigger warning as something that it isn’t.

The article’s introductory caption shockingly stated, “In the name of emotional well-being, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don’t like.” That is an unverified, unacceptable lie.

There is no national movement among college students to censor discussion of mature topics. I would encourage those to draw on their own experiences at college, or ask a student who is in college, if they have ever seen a discussion censored by a trigger warning. That is not what a trigger warning is, and that isn’t their function.

The piece correlates trigger warnings and macroaggression framework with anecdotes of students overreacting to things that aren’t trigger warnings or macroaggressions. The article’s example of Harvard Law students petitioning professors not to teach about rape law has nothing to do with trigger warnings.

That is an example of censorship, but if the course had employed a trigger warning, then the professor could have circumvented the negative reaction from students in the first place. These unrelated anecdotes appear numerous times in the piece, and they destroy the writer’s authority.

In order to avoid future misconceptions about an alleged link between trigger warnings and censorship, here is a guide on what trigger warnings are, and how they actually help discussions.

Trigger warnings are specific messages directed at students who have experienced traumatic events related to the material to be discussed. Employed properly, they do no more than warn students who might be susceptible to panic attacks or other emotional trauma of what is to come.

I contend that these warnings serve an important purpose and facilitate a better discussion. A trigger warning can help teach students that the topic at hand is important and emotionally traumatic to people. Alternatively, if a lack of a warning led to emotional trauma for a student or a group of students, the discussion would be totally derailed.

Trigger warnings help create an environment for discussion where no one has any excuses to be overly emotional, but also one where apathetic students will be less likely to downplay the seriousness of the content. Lastly, they might just give a victim a chance to recluse oneself from a harmful emotional episode.

What these warnings don’t do is eliminate discussion of volatile subject matter. On the contrary, they allow those important discussions to take place.

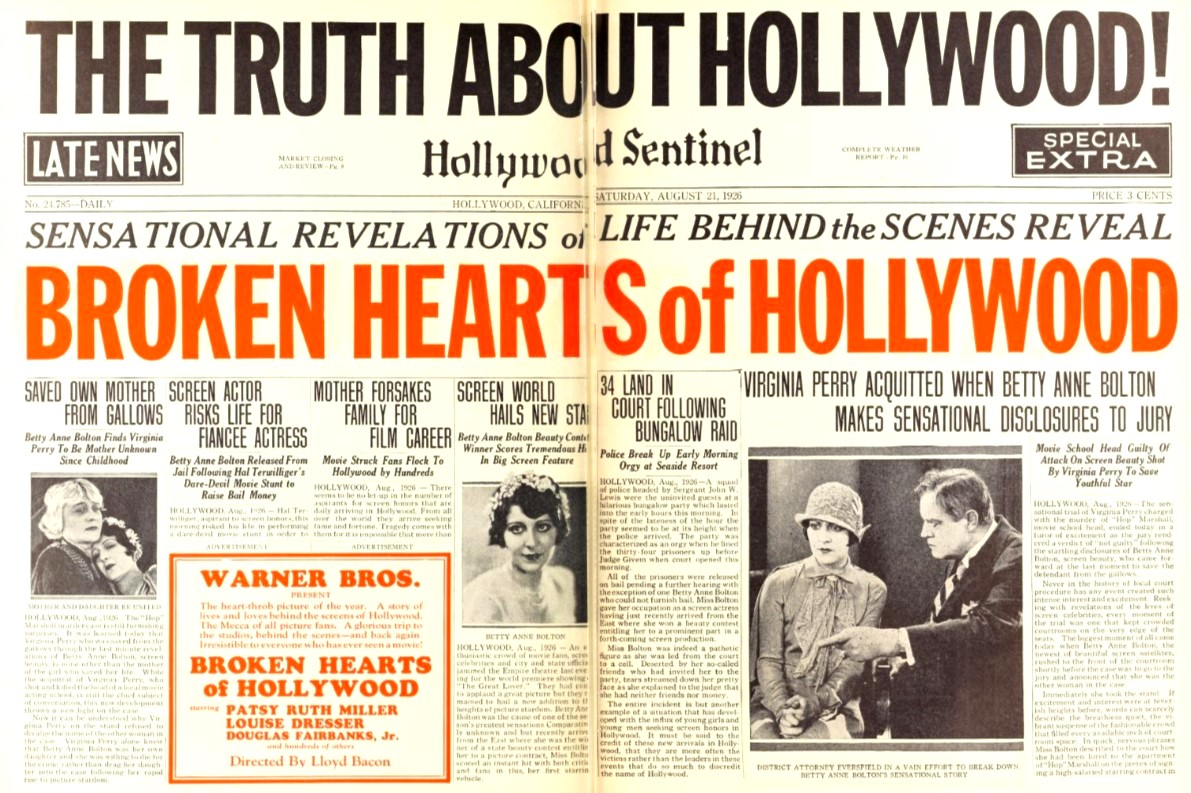

Trigger warnings carry a negative association at the college level, but we accept them everywhere else in our lives. Our movies and video games have MPAA or ESRB ratings. News stories have graphic content warnings.

When schools show adult movies to teenagers or read adult literature, they require parent signatures to do so. Where is the outcry against these practices? I’ve never seen a feature in a popular national magazine argue that movie ratings censor subsequent discussion about the film.

The only reason that criticism exists for trigger warnings but not for content warnings is because most Americans aren’t in college right now and don’t have a functional understanding of what a trigger warning is.

Here’s how a trigger warning usually goes. The most common way is in a syllabus, since warnings immediately before mature content are less effective. During the add-drop period of a college course, the professor may issue a warning that his or her course contains potentially objective material.

In my case, this happened in introduction to black studies, where the professor simply mentioned that we would discuss and read about the kidnapping, enslavement, and mistreatment of Africans. The students in the course were not given any choice in the matter. We had no way to object to or censor the professor’s intentions or even subvert the discussion.

The only reason the warning existed at all was to allow students to drop the class if they didn’t want to discuss those issues, or at least choose to stay in the class despite the traumatic thoughts that the discussion might bring up. Not one student raised their hand or commented on the trigger warning.

No one left the room. It took about two seconds for the professor to mention the warning, and we all moved on to a semester of vivid discussion and lecture.

The Atlantic would have you believe that this sentence in our syllabus impedes intellectual discourse on a national scale. The next time someone spouts off on that idea, I encourage you to remind them of what trigger warnings actually are, and the benefits they bring to a discussion.

William Keve is a collegian contributor and can be reached at [email protected].