I didn’t lose my virginity. I know exactly where I left it: on the couch with the older boy I thought was my world. There was a part of me that felt like I owed it to him to give up a piece of me while he just got to “take my virginity.” Our mutual friends congratulated him when they found out, almost as if they were celebrating a conquest.

Looking back, my sexuality was all mine, and not his to take or conquer.

I was one of the first people in my friend group to “lose their virginity.” I was asked all these questions on if I thought he was “the one” or if it was “the right time.” I didn’t have the answers. If I said yes, then it was okay. If I said no, I was desperate. My mom would say, “You want to wait until someone special to lose it.” But I questioned if I was actually losing anything. How could something be taken away from me if I wanted to share a sexual experience?

Virginity is not a physical concept; you cannot take it nor give it. Sex should be something created, defined and shared between people, not taken from one by another.

What even is sex? Is it physical? Emotional? Both? Neither? I’m still trying to figure that out.

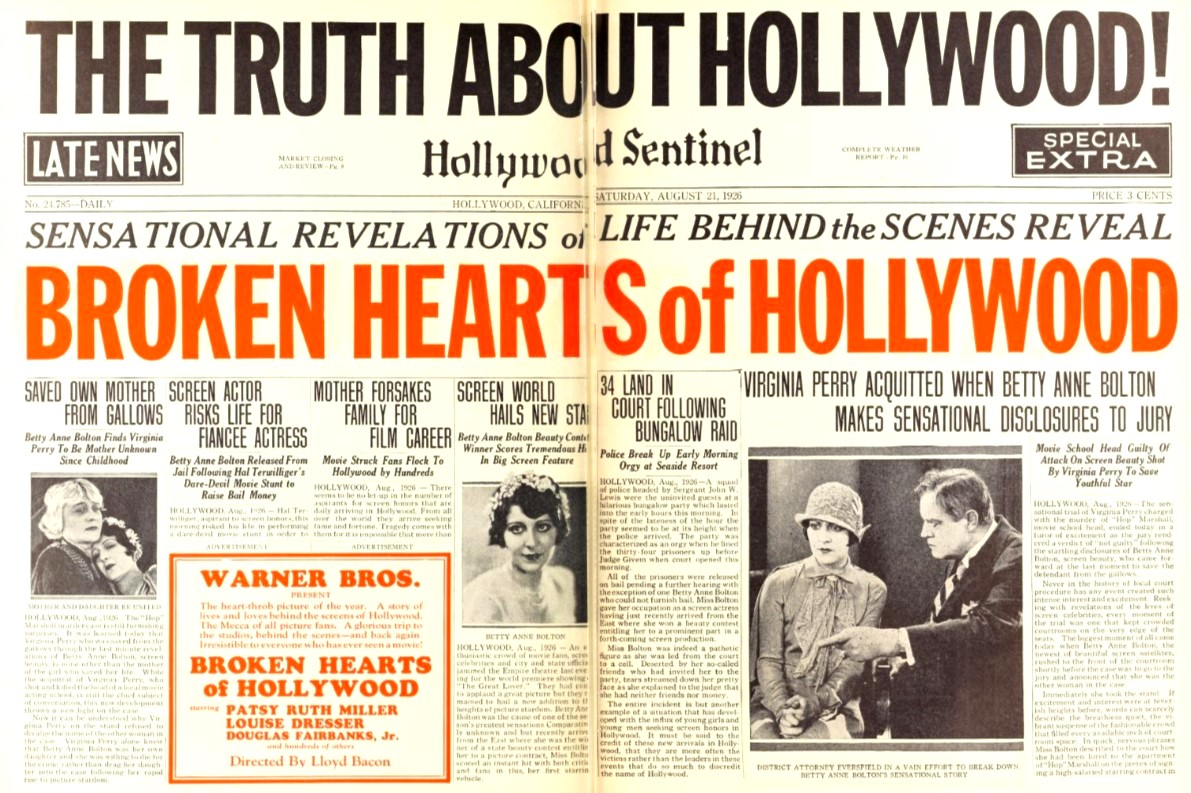

Western cultures obsess over virginity. Sure the concept of virginity affects men, but the social implications that come with female virginity are seen as “more valuable.”

“The Purity Myth” by Jessica Valenti breaks down the notion that, the first time sex happens, women give away a part of themselves while men are not whole until they capture that virginity. This idea is just ridiculous because when engaging in sexual activity for the first time, nothing is being lost. Control, conquest and captivity are all Western ideas that dominate discourse of all sorts, so it is not surprising these structures are shaping sexual narratives.

Virginity is rooted in misogyny, cis-male dominance and heteronormativity. The concept of virginity was created to shame people’s sexualities and their experiences. Men can use the notion of virginity to control and subjugate women and to make them ashamed of their bodies and identity. There is a double standard when men gain sexual experience: it’s encouraged and celebrated. However when women become sexually active, they are “slut-shamed,” or labeled as easy and desperate.

Our culture also defines sex as “penis in vagina” penetration, and often leaves out other sexual narratives. Erin McKelle from Everyday Feminism says, “It’s assumed that unless you’ve had a penis in your vagina, or put your penis into a vagina, then you haven’t really had sex. Somehow, even oral and anal sex don’t really ‘count’ in our culture, despite both having the word ‘sex’ in them.” When sexual activity that doesn’t fit the heteronormative standard occurs, the sex is seen as invalid and not real. Virginity assumes heterosexuality and erases the sexual experiences of queer, non-binary and trans people. Gender is not defined by a person’s genitalia, so how can we talk about sex without including narratives of those who don’t adhere to the binary?

I believe virginity doesn’t have to be related to morality. Sex should be consensual and defined as whatever a person chooses it to be. Sex can be based on emotion, it can be based on physical feeling, anything. Does it even need to have a definition? Probably not. In terms of my sexual narrative, I didn’t lose anything the day I skipped school with the older boy. I debuted my sexual self, to myself. I explore this everyday and think critically about what virginity and sexuality are, and how I can actively work to dismantle patriarchal structures that commodify these sexual experiences.

Erika Civitarese is a Collegian columnist and can be reached at [email protected].