Rashaan Holloway demands the attention of every pair of eyes in any room he ever walks into. A giant, standing 6-foot-11, weighing 320 pounds – it’s impossible to miss or overlook Holloway when in his presence.

On the outside, the intimidation factor is imminent. His sheer size alone is enough to instill fear in anyone who crosses his path. However, there’s more than what meets the eye to understand this beast. He’s well-spoken and thoughtful in everything he says. Teammates and coaches adore him and his gentle personality on and off the court.

But as good and dominant a force Holloway is on the basketball court, there was a real possibility he wasn’t going to get the opportunity to play at a high level of Division I college basketball. His problem is one that millions of people face every day.

At his peak, Holloway was bigger than Vince Wilfork, Warren Sapp and almost every offensive and defensive lineman who’s ever played in the NFL. He was more than 25 pounds heavier than Shaquille O’Neal and had another 50 on Yao Ming.

Holloway’s basketball abilities were never in question when determining whether or not he could have a successful career both at UMass and beyond. His hands and footwork are unprecedented for a man of his size and physical stature, and the bare of being a college athlete was never the issue.

His weakness? Something most people are too scared and embarrassed to admit.

“The hardest part is eating when no one is looking,” Holloway said.

Holloway knows there’s no better time than the present to create a name himself and for his future as a basketball player. He has the support to do so, and now he’s ready to prove to everyone that he’s a changed man.

Putting in the work in the classroom

Like most immature high school adolescents, Holloway never cared much for his grades or academics and spent the majority of his time focusing on basketball.

Attending Arthur P. Schalick High School in his hometown of Elmer, New Jersey, Holloway made an instant impact on the court, prioritizing the game he loved over his school work.

“I remember as a freshman, I hated school so much,” Holloway said. “I hated being there. I was just lazy in the classroom.”

But Holloway’s parents, along with his high school coach, Eric Cassidy, knew that in order for him to make a name for himself, his basketball abilities could only go as far as the work he was willing to put in the classroom.

It wasn’t until after his freshman year that Holloway took his grades more seriously. Knowing basketball was a potential outlet to attend a Division I school and receive a free education, Holloway took the time to work with tutors and spend time before practice studying and working on his homework.

“Coach Cassidy was awesome, but it was more of his father staying on him,” his mother, Yolanda, said in a phone interview with the Massachusetts Daily Collegian. “His father was like, ‘if you want to get there, you have to push yourself in academics first.’ His father told him basketball meant nothing if he didn’t get his school work done.”

“As a coach, I really harp academics,” Cassidy said in a phone interview with the Collegian. “Like I always tell kids, with basketball or any sport, if you don’t have the grades, I don’t care how good you are.”

With an increased focus on academics after his freshman year at Schalick, Holloway began making a bigger and bigger impact on the basketball court. In the summer going into his sophomore year, he grew five inches from 6-foot-3 to 6-foot-8 and that’s when basketball took off in his life.

“His freshman year he couldn’t walk and chew gum at the same time,” Cassidy said. “He was one of the hardest working kids to get where he needed to be.”

As Holloway grew, the weight proportionally followed suit. He was big, but it was never an issue that diminished what he was doing on the court.

“He’s by far the best player I’ve ever coached,” Cassidy said of Holloway, who scored 1,622 points in his high school career. “Just from the standpoint of how dominant he was for a kid that didn’t shoot the ball a lot. He was just dominant in all aspects of the game – rebounds, blocking shots, making people better.”

After a pair of back-to-back postseason runs in the South Jersey Group I playoffs, Holloway, along with his brother Michael, and two lifelong friends Melvin Allen and DeAndre Solomon, led the Cougars to the South Jersey final, before falling in the championship game.

“I knew I was big when I was a sophomore in high school,” Rashaan said. “As you get taller, your weight just starts going up and you learn to play with your body – I was still learning basketball. My junior year I started playing everywhere, and people started enjoying watching me play. I got some college looks and stuff like that. I’d have my standstills some times, where people didn’t know if I was going to go to college because of my grades.”

Cassidy said seeing Holloway graduate high school was one of his proudest moments as a coach. All the hard work and extra hours paid off.

Holloway was going to college to be a Division I basketball player.

Becoming a man

Massachusetts basketball coach Derek Kellogg was on the beaches of Martha’s Vineyard somewhere between Oak Bluffs and Edgartown when he got the phone call that would change the outlook of his team.

Vacationing with his wife Nicole, the Kellogg’s stopped at a random beach to take a dip in the water. For whatever reason, Derek ventured waist-deep into the water with his cell phone when he got the phone call.

It was Rashaan.

“I answered the phone and they said ‘we made our decision,’” Kellogg said. “It’s weird, like I’m in the water, he just visited recently, and I’m thinking ‘this fast?’ and they were like ‘I’m coming to UMass!’”

“I started kicking water and splashing and said to myself ‘this is the best vacation ever!’ When you get a good surprise like that when you’re in a place like that, it’s just awesome.”

As happy as Kellogg was knowing he just landed his – literal– biggest recruit as the head coach of UMass, like all good things in life, he was forced to wait.

Arriving prior to the 2014-15 season, Holloway was sidelined his first year on campus with a knee injury that required surgery. He said and did all the right things, learning from his teammates and coaches on top of improving his grades academically.

But as he watched from the sidelines, it took a toll on his body.

“It was tough,” Holloway admitted of the year he was injured. “With that, my weight went up.”

“It was devastating to our whole family at home,” Yolanda added. “As a mom going up there and seeing him with the surgery I realized that he loved the game and that I knew in my heart it was going to be rough on him.”

After reaching the NCAA tournament for the first time in 16 seasons the year prior to Holloway’s arrival, the Minutemen failed to make a return trip to the Big Dance. Holloway went back home, ready to start his career at UMass.

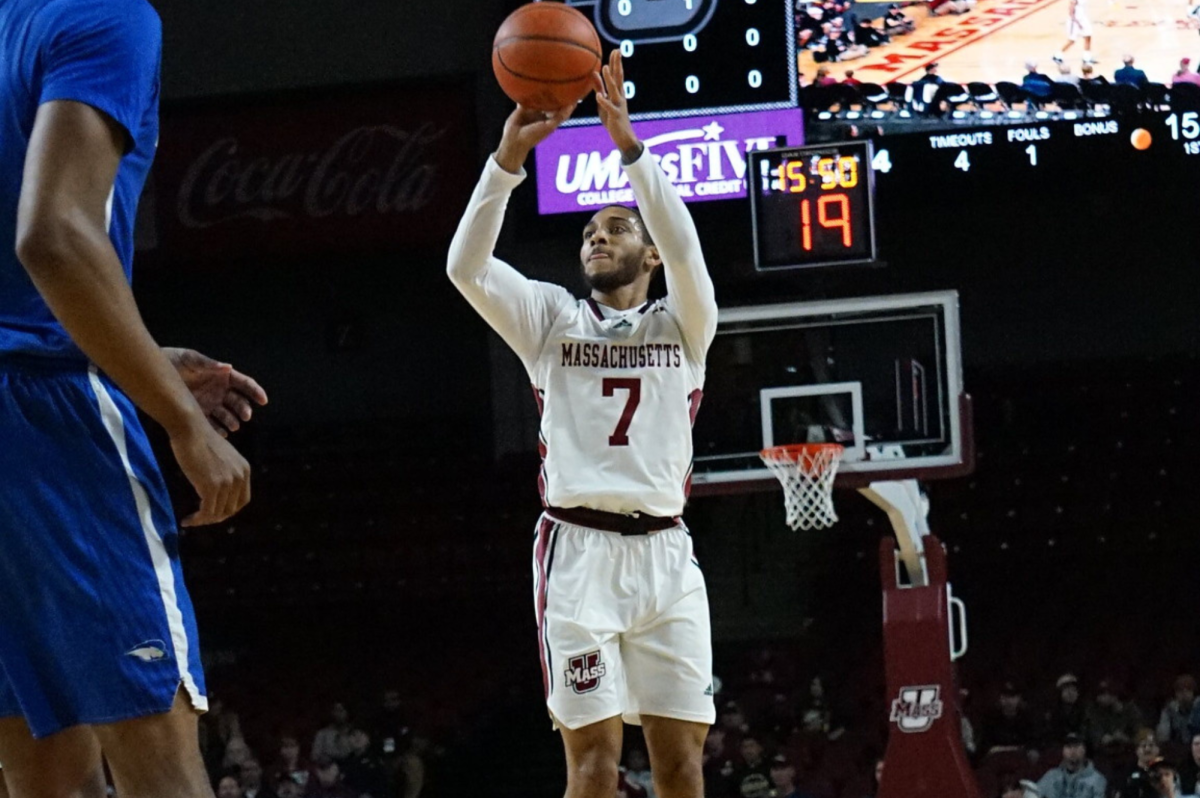

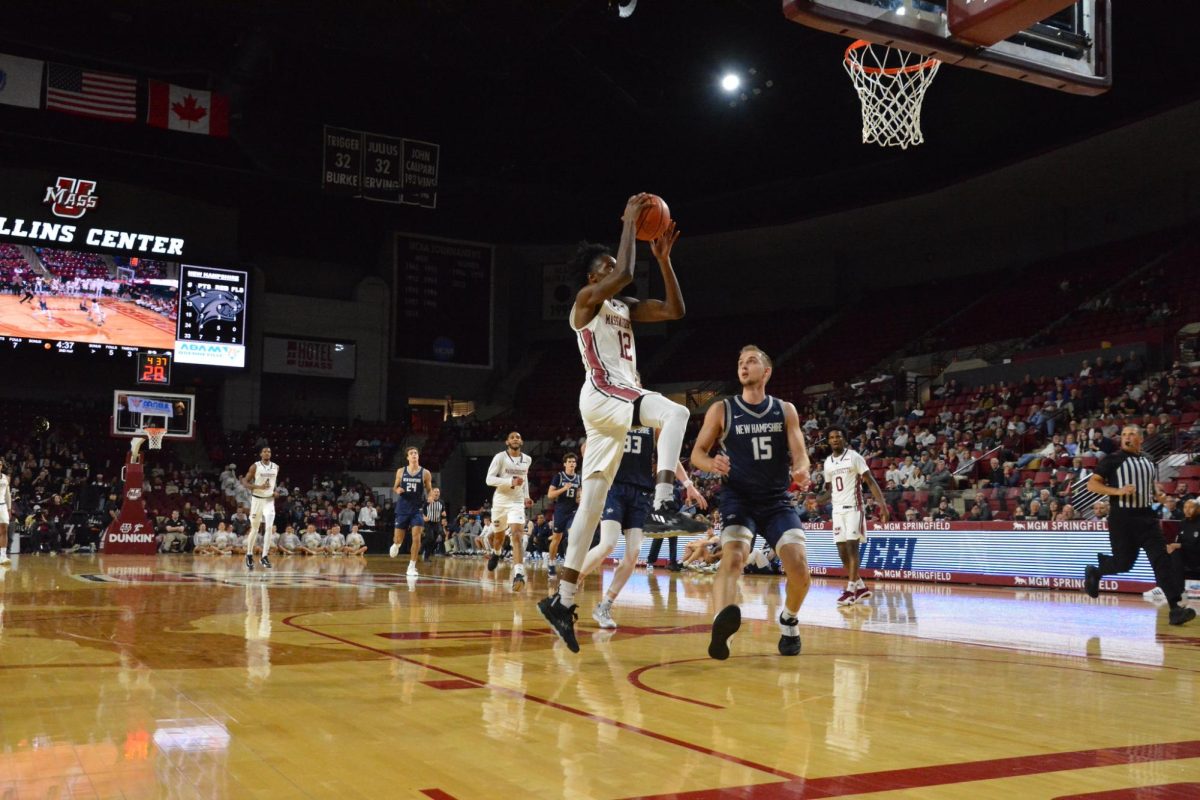

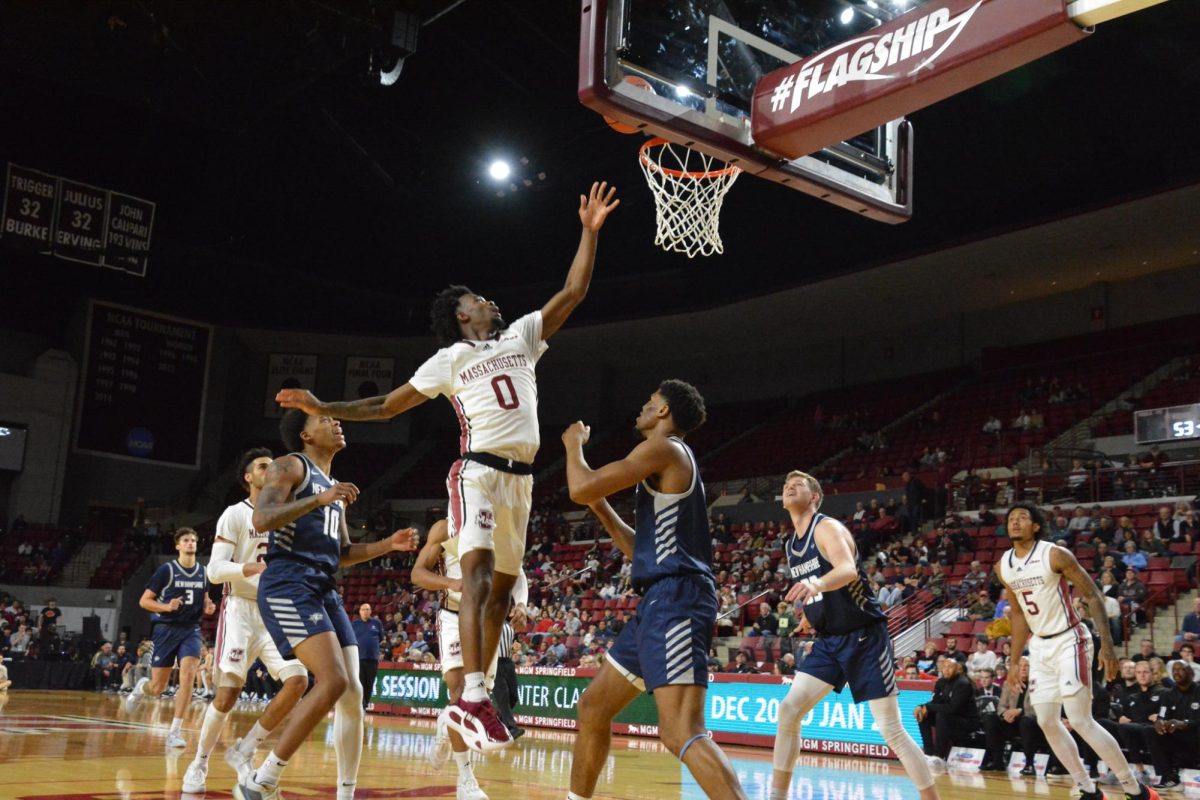

Holloway only scratched the surface with his talent during the ’15-16 season as a freshman where he appeared in 30 games, including 14 starts. Despite making his presence felt while he was on the court, his conditioning and weight limited him to just an average of 11.7 minutes per game. He’d play well in spurts, but that’s all his body could handle.

It wasn’t until the Minutemen’s 86-74 loss against Davidson midway through the season that Kellogg and the rest of the coaching staff put their foot down to make a change.

“It was kind of after the Davidson game last year when we were in a position to beat them and he had a layup where I don’t think he got above the foam (on the backboard) on the layup and he either got it blocked or he missed it, and then they went on a run,” Kellogg said. “I pulled him aside and I kind of told him, ‘you have to get yourself in shape because that should never happen.’”

Kellogg added: “We came back and kind of weighed him and went over some things. Not to put him on the spot, but just to see where we are at and that was kind of the building spot from that point on. From that point on he really started to taking his conditioning seriously.”

That’s when UMass and strength and conditioning coach Rich Casella made a plan. At the time, Holloway weighed 364 pounds.

“The process itself started with education and then discipline before it evolved to the specifics,” Casella said. “Through trials and tribulations, we kind of found what works for him as opposed to what works for science.”

“Through last season, we had our trials and tribulations again, but once the season was over, it was go time,” Casella added. “He got real focused about his weight loss, real focused about just giving himself to me and allowing me to dictate the path we would travel.”

During the summer, Holloway, with the help of Casella, created a five-day workout regiment with a heavy focus on cardio and conditioning. One day was dedicated to steady-state cardio, where he maintained a steady heart rate of 135-165 beats per minute for as long as he could. Another day was for high-intensity interval training, where he would do various cardio drills to spike his heart rate up periodically throughout the workout.

One of the days was geared toward lifting weights, where Casella would put Holloway through a lifting circuit full of rows and presses until fatigue set in. The fourth day was all basketball-related exercise where he would use medicine balls to mimic the fatigue of playing long minutes in the season. The final day was spent underwater, treading water as long as he could.

“He really became my 6-foot-11, 370-pound little brother because we spent so much time together,” Casella said. “Not only would we work out together and train together, we’d walk there and we’d drive there. Our relationship was able to be built through just spending time together. Once things started to get a little more serious, once coach told him what type of role he would have on the team, I started finding different ways to motivate him and try to find different ways to bring it out of him.”

On top of all the drills Casella put Holloway through, the pair would switch it up from time to time. Some days Holloway would create his own workout regiment where he dictated the workouts for the day. If Casella didn’t approve, he added to it until he felt it was difficult enough.

Other days the two would put 20 minutes on the clock and did nothing but box each other out the entire time – pushing and shoving each other until the time was done.

“My relationship with Rich is more than any player-coach (relationship),” Holloway said. “We have a bond; we have a friendship going on.”

For Holloway, accountability was the biggest component to his lifestyle change. Rather than put him on a diet, Casella forced Holloway to send him picture messages of every meal he ate, breakfast, lunch and dinner, to stay on top of what he was putting into his body.

Casella was up at 4:30 a.m. every day setting alarms when to call or text Holloway about making sure he was eating right and drinking plenty of water. On any given day in the summer, Holloway was drinking upward of two gallons of water per day – 16 pounds of pure water weight.

“I think it was super important and I really think it came down to how many times we failed before we succeeded,” Casella said of the difference between putting Holloway on a diet versus making a lifestyle change.

“That lifestyle change with him was probably the biggest difference. Once he flipped that switch and his weight became apparent to everybody else, he became insatiable, and I’m not just talking about in the kitchen, but in every other aspect in his life.”

“When people are looking at you, like after practice when we have our team meals, people were watching me eat so of course I’m going to pick up a salad,” Holloway said. “But when I go to my room, I’m not actually eating salad, I’m not actually eating what I’m supposed to. And it took me a long time to do that. It’s even a struggle for me to do that now, but I’m just more disciplined to that.”

During the summer, Holloway missed only one workout. The next day when the team went in for a lift, Casella made him go outside in the heat of the Amherst summer with a 60-pound weighted vest on.

As the team lifted, laughed together and enjoyed themselves, Holloway was in solidarity doing burpees. The entire time.

“After that he came to me and he only said one word,” Casella said. “We brought it up, I said ‘alright Rashaan, get in here. You missed your workout, you took your medicine, it’s over, it’s squashed.’ He just said one word.”

“I just looked at him and said respect and just kept on walking,” Holloway said.

“That was when I realized I can’t do immature stuff. I can’t miss workouts just because I’m tired. I can’t just do whatever I want to do. He changed that for me. He made me look at things different. It was almost like he made me workout without the team – like I was selfish for missing the team workout.”

Keeping it off

As his sophomore season approaches, Holloway remains the key cog for the Minutemen’s success in 2016-17. In an era full of small-ball, four-guard rotations, the traditional center position has become obsolete in college basketball.

In order for Holloway to be successful, he knows it won’t be how hard he practices or how much extra time he spends in the weight room. It’s about what he eats and what he puts into his body.

To keep tabs on him, Casella makes Holloway weigh himself every day when entering the facility – something he does for every player on the Minutemen – but for Holloway it’s different than everyone else.

“For Rashaan, it was every day for accountability,” Casella said. “Even though I think he has it intrinsically now, just that little bit to quantify what he’s actually doing on his own time is a big difference maker.”

“I know I have to do more work to make sure it is going down,” Holloway said. “I proved that to him over time.”

Holloway’s weight-loss journey isn’t complete, nor will it ever be. It’s a 24/7 cycle that requires constant precision and dedication to ensure he’s not slipping into his old habits.

“Don’t get me wrong, it was hard,” Holloway said of the progress he’s made. “I feel like I’ve gotten to a point now where I see something that’s unhealthy, I look at it as nasty. I look at it as nasty.

“So like yeah, I might like to take a little piece of it, but that’s all I need. I look at it as disgusting – that always works for me and it’s still continuing to work for me.”

Holloway plans on playing professional basketball at a target weight of 295 after his career is done with the Minutemen. Even if it isn’t in the NBA, he hopes on playing overseas to support his family, friends and his son, Rashaan Jr.

“He now views basketball as his job,” Yolanda said. “He has to work hard to do that because his son is looking up to him. He has the opportunity to prove to himself and his son that he’s the father and the man he should be. He wants to make a career out of this. He knows he has to do best for his son.”

But most importantly, he’s doing this for himself.

“I want to prove this to myself,” he said. “I just want to prove them that I can do that. I want to show everybody that I’m not an invisible person in college.”

Andrew Cyr can be reached at [email protected], and followed on Twitter @Andrew_Cyr.