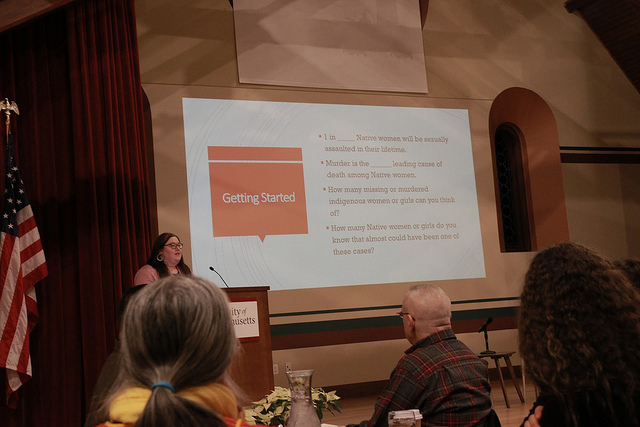

Students and non-students, indigenous and otherwise, gathered at the Old Chapel building at the University of Massachusetts last Friday to hear a personal account from a survivor of abuse and trafficking.

Key Speaker Annita Lucchesi comes from Southern Cheyenne descent. She described her escape from an abusive relationship and subsequent trafficking to find a new purpose: recording acts of gender and sexual violence against Indigenous women.

Any information about the victims, their perpetrators and aspects of the situation goes into her “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Database,” created in 2015. It includes cases from given communities dating back to the early 1900s.

While originally focused on cases of women, girls and two spirit people in the U.S. and Canada, Lucchesi said she has made steps to expand into Latin America as well.

UMass senior Brooke Yuen, event coordinator of the Josephine White Eagle Cultural Center and Vice President of the UMass Native American Student Association, introduced the aforementioned sponsors for the event.

In an interview before the announcements, Yuen called the phenomenon of missing and murdered Native women a worldwide epidemic that people fail to perceive.

“Being indigenous, you kind of hear about it,” Yuen said. “The people who are not indigenous may not think or know that this is a huge problem… So, when we were brought up the task to make a conference for our cultural center, we thought that this was the most important conversation we needed to start on the UMass campus.”

Lucchesi started the conversation with an overview of her experiences, adding that cartography gave her the greatest sense of ownership in terms of telling her story.

“It ties our stories directly to the land, which is an indigenous value that Indigenous people from all over the world carry, and it helps us to decide the parameters and the boundaries of what kind of stories we tell and how we tell them,” Lucchesi said.

Left homeless and without any material wealth following a relationship that nearly killed her, Lucchesi described moving to New Mexico with only her education to help make sense of her genocidal experiences.

When she realized that available data about crimes against Indigenous people varied greatly between often outdated studies, she decided her database should have “a good working number of cases.”

Through presenting statistics recorded on the database, Lucchesi and others outlined a negligence to the scope of violence against Native women, part of it tracing back to law enforcement practices.

“We know that law enforcement data is super unreliable, not just because cases go unreported, but because sometimes law enforcement won’t even take the case,” Lucchesi said. “So there’s all sorts of times where families come shooting in and say ‘hey, I tried to report my cousin or my niece or my daughter missing,’ and the police say ‘well, come back in a week, she’s probably just off partying.’”

Lucchesi noted in her conference that, per her database records, two out of three cases are murder cases, with a little over half consisting in the U.S. Yuen also stated in her introduction that one out of three Indigenous women are sexually assaulted in their lifetime.

One of the stories Lucchesi related to negligent law enforcement detailed the death of Tina Fontaine, a 15-year-old from Winnipeg, Canada in foster care who went missing in August of 2014. According to Lucchesi, police pulled over the truck of an older white man with Fontaine the night before he killed her, and despite discovering she was high, the police let them both go.

“Any law enforcement would have known… she’s not safe in the situation she’s in and we need to pull her out of the truck and make sure she’s not here anymore,” Lucchesi said. “But they let her go, and the next day, she was killed.”

Lucchesi encouraged people to fight against this through talking with local law enforcement about cases in the area. She also advocated for active “decolonizing research,” which she defined as “doing research with good relationships and with a great heart.”

“I would venture a guess that hopefully most of you, if not all of you, are approaching your work with a good heart outright,” Lucchesi added.

Audience questions followed after the presentation, as did a question-and-answer session with Michelle Youngblood, assistant director and student success coach for the Center for Multicultural Advancement and Student Success.

The evening ended with Native American artist Susan McCarville, a fellow survivor of abuse both as a child and a married woman, giving instructions to create little red dress pins to commemorate the MMIW movement.

McCarville said, “The red dress pin is not my idea, it’s something… it’s something I’ve embraced with a lot of passion because it does bring such great attention to something that I firmly believe in.”

She also addressed the crowd briefly to talk about the red dress she wore for the evening in honor of a San Carlos Apache woman whose rape case failed to acknowledge her ethnicity.

“Within 20 hours, the fact that she was Native was kind of swept under the carpet and forgotten,” McCarville said. “The story was still out there, she’s still a victim. She was raped while she was in coma by someone who was chosen to take care of her. The baby’s doing fine. She was San Carlos Apache. They want us to forget that.”

Last month, the Sovereign Body Institute launched as the new home for the MMIW Database, with Lucchesi appointed as executive director. In addition to collecting documentation of violence against Indigenous women, the Institute also partners with tribal nations and Indigenous organizers for other projects detailed on the website.

John Buday can be reached at [email protected].