Science and math have never been my thing. In middle and high school, math and science were always classes I struggled in, no matter the subject or difficulty of the class. Try as hard as I might, I just could not understand science, let alone math.

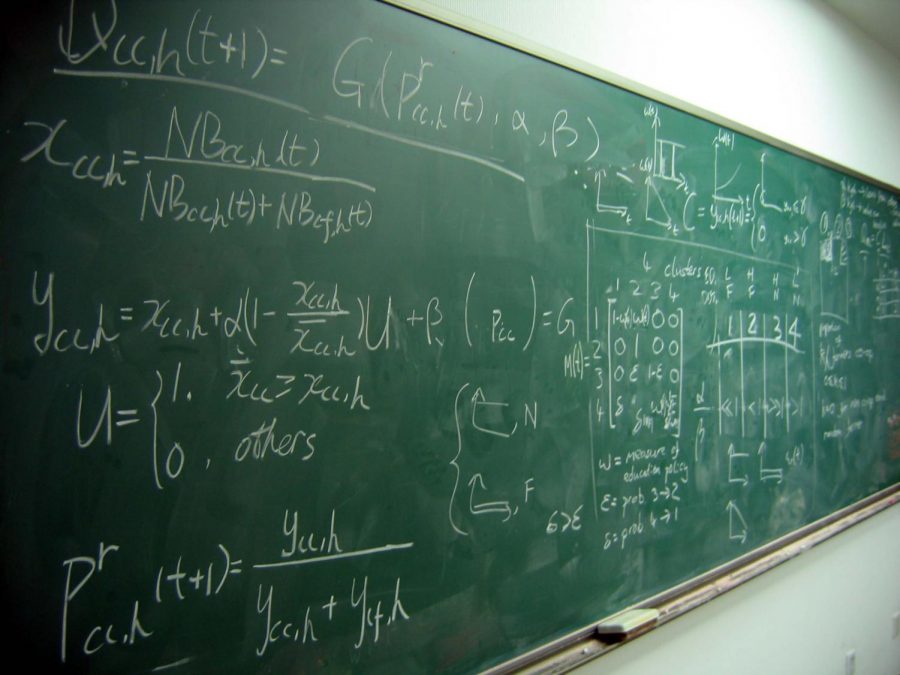

Coming to the University of Massachusetts, I thought I could escape math and science all together, but the university’s general education requirements said otherwise. Taking my basic mathematics, analytical reasoning, biological and physical world requirements were like pulling teeth. I appreciate that UMass gives me interesting opportunities to make these classes a little less painless, but they’re still science and math. I’ve always tried to give them a chance, but it still just doesn’t click for me.

I’ve always been a student who has excelled in English, history and the arts, so the opposites of those subjects cause me to struggle. This situation may be similar for people who excel in science and math. They might not understand Shakespeare, comma rules or the Cold War as well as other students. No student is the same in what they succeed and struggle in.

In wanting to comprehend why I couldn’t understand science, I considered my learning and personality types. There are three types of behavior learning: classical conditioning, operant conditioning and observational learning. Classical conditioning is learning from the stimuli in one’s surroundings, while operant condition is from trial and error. As for observational learning, well, people learn via observing. As a visual learner, observational learning seems the best fit in most of my learning situations: I watch how something is done and then I do it and hopefully get it right. Yet when applying that same learning to math and science, no matter how many times you show me a mathematical property or the oxidation state of iron, I still won’t get it.

There’s a common notion that artistic people use one side of their brain more than the other side and vice versa, but according to Hank Green, in a Crash Course psychology video that simply isn’t true. According to Green, that idea is geared towards pop psychology or cultural psychology.

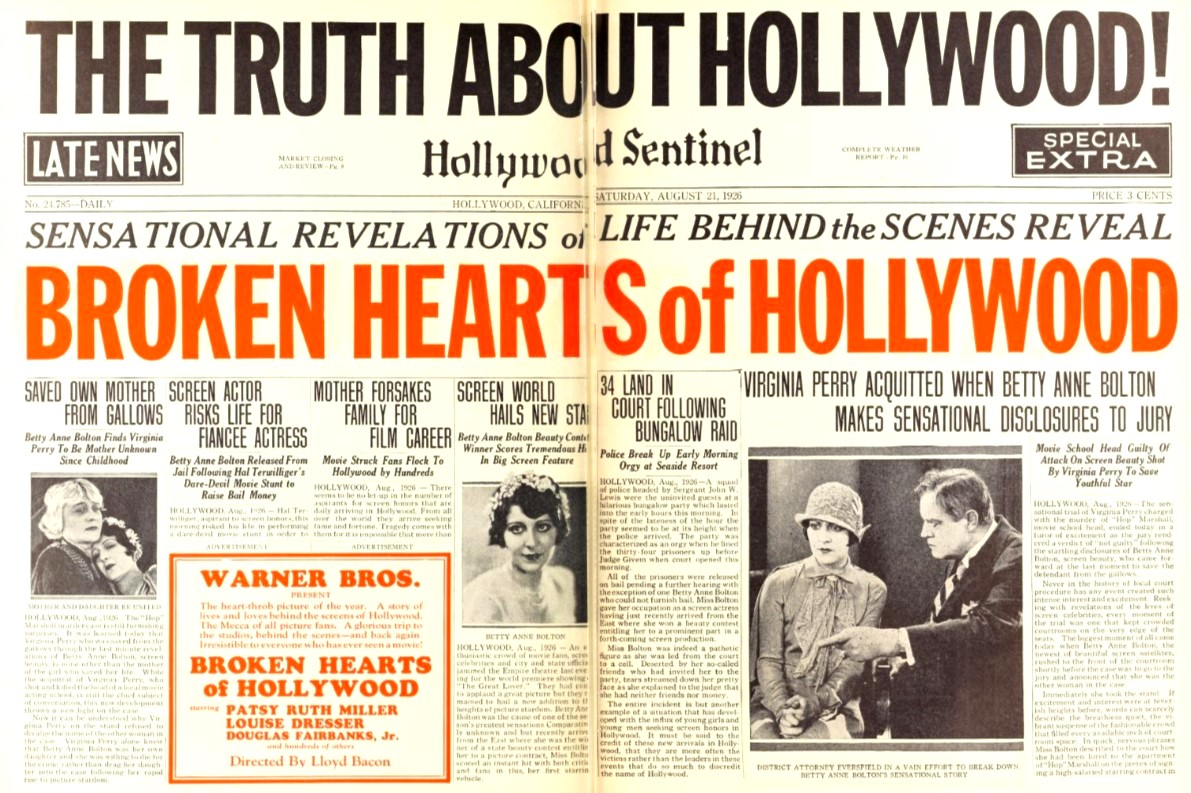

I also feel like the education system has pressured students to believe that they have to like and have a career in STEM, and that’s why I dislike math and science so much. There have been numerous occasions where I was told I should take up an occupation in the world of science because I would make a lot of money. Being able to pay the bills is certainly a priority, but I would also like to enjoy what I do for a living. It’s the same as “you lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.” You can tell me that STEM is a good career for me, and I can make a lot of money, but that doesn’t mean I want to actually work in STEM.

Patricia Cohen, a reporter for The New York Times, wrote an article in 2016 on state funding cuts for humanity majors to push students towards more job-friendly occupations. Cohen presents information on who is cutting funding and the reasoning behind it. She goes on to mention the growing concern for getting a job out college and the earning behind those jobs.

Cohen also brings up a salary survey from NACE, the National Association of Colleges and Employers, where STEM fields take the top three spots, making $55,000 for entry level jobs. In an updated survey from NACE, STEM fields took the top four spots, with an increase in starting salaries. There is no surprise that computer science is at the top, making $71,000 as a starting salary.

Maybe the problem is simply I don’t like science or math. Plain and simple. If the whole journalism thing doesn’t work out for me, I do have a backup plan. I could be an electrician or a businesswoman or join the military. But until that happens, which I know it won’t, STEM will never be my friend.

Nicole Biagioni is a Collegian columnist and can be reached at [email protected]