It’s hard to imagine that a horror movie released in 1978 could maintain cultural resonance and, most importantly, manage to frighten audiences 40 years later. Yet “Halloween,” written and directed by John Carpenter and Debra Hill, has remained one of the most beloved horror films for over four decades and its impact on horror as a genre is universally recognized. “Halloween” is most significantly the origin for what would quickly become many of the genre’s staples, but the key to its longevity lies more in what it doesn’t do and doesn’t show rather than what it does.

Admittedly I just got around to watching “Halloween” this year, as I generally prefer psychological horror over slashers. It came as somewhat of a shock that the film, often hailed as one of the first true slashers, has less blood and gore than most cable television shows. Much of the movie is obscured so the film essentially forces the audience to develop a personal stake in the events. Key details like the killer’s face, the murders themselves and the majority of the characters’ personal lives have been omitted. This leaves a minimalist, low-budget outline of a horror film that relies almost solely on carefully crafted suspense that bounds the viewer’s imagination.

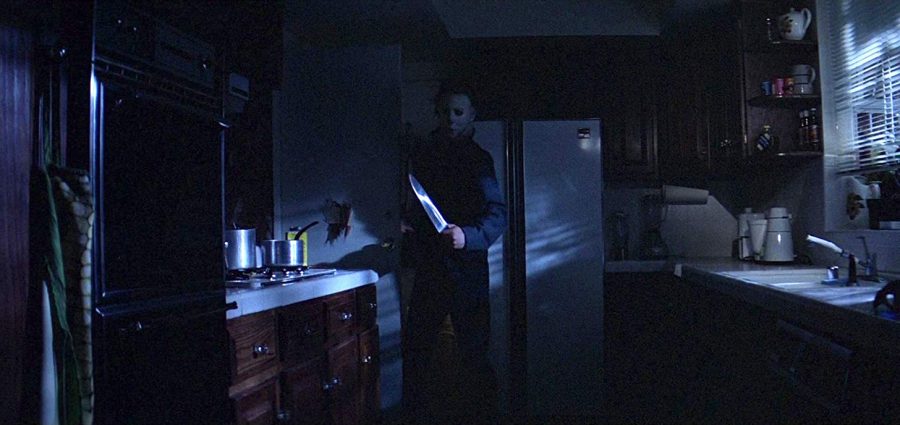

The crux of the film’s rise to cult-classic status is the character Michael Meyers, a villain so chilling and intriguing that he has inspired countless sequels and last minute Halloween costumes alike. At first glance Meyers is an unembellished psychotic killer; an amalgamation of every cliché from the disturbed kid to the recently escaped lunatic. But those familiar qualities are just the foundation for what really makes him terrifying. Meyers doesn’t chase his victims, torture them or even speak before he kills them. The only thing he does is wait and watch. In fact, the majority of the film is interspersed with increasingly disturbing glimpses of Meyers keeping a watchful eye on Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) and her teenage friends. He witnesses all of the promiscuous behavior that Laurie’s friends engage in and he lets it play out, only making himself known at the last second. This pattern establishes Meyer as both a voyeur and moral judge; both of these roles threaten the assumption that in private, we’re safe from outside scrutiny and therefore free of certain social constraints. But in the world of “Halloween” nothing is private, not even a character’s own home and the supposed moral failings are swiftly punished.

The fears that arise from suburbia provide the basis for the most frightening elements of “Halloween.” Parents fear what their kids might be up to on a Friday night, the teenage girl walking home from school fears someone might be following her and the babysitter who answers an unknown number of fears what she might hear on the line. “Halloween” takes all of those mundane fears and intensifies them while still preserving enough realism to be believable. The result is equal parts fun and horrifying, as the audience is both eagerly anticipating and dreading every confrontation between Meyers and the teenagers of Haddonfield. It’s undeniably thrilling to watch the night devolve into chaos but after the movie is over, it’s difficult to avoid imagining how a similar situation would play out in one’s own home.

The fact that “Halloween” was filmed in only 20 days on a remarkably low budget of $300,000 is most evident in the sparse, thoroughly generic setting. Virtually nothing about Haddonfield is too idiosyncratic to apply to nearly any small town. Even the script feels run-of-the-mill in some places; Laurie and her friends gossip about boys and parties while jaded psychiatrist Dr. Loomis (Donald Pleasance) delivers a hard-boiled account of his time working with Michael Meyers.

That minimalism is an essential component of “Halloween” and its continued ability to scare. It allows the film to transcend the pigeonhole of 1970s horror and makes it easy to imagine this particular story taking place in any decade. Haddonfield could be any town in America which is what makes “Halloween” terrify everyone who sees it because the next time you look out into your yard, you might catch a glimpse of Michael Meyers.

Molly Hamilton is a Collegian correspondent and can be reached at [email protected]