When Sophia Boyd, a senior nursing major, arrives at the Mullins Center, it’s 8:30 a.m. She’s assigned to the flu shot clinic, around the far end of the building facing Southwest Residential Area.

Jordan Hoey, another senior nursing major, walks in at about the same time. Today he’ll be observing testing. Just a couple of hours spent watching people stick cotton swabs up their noses.

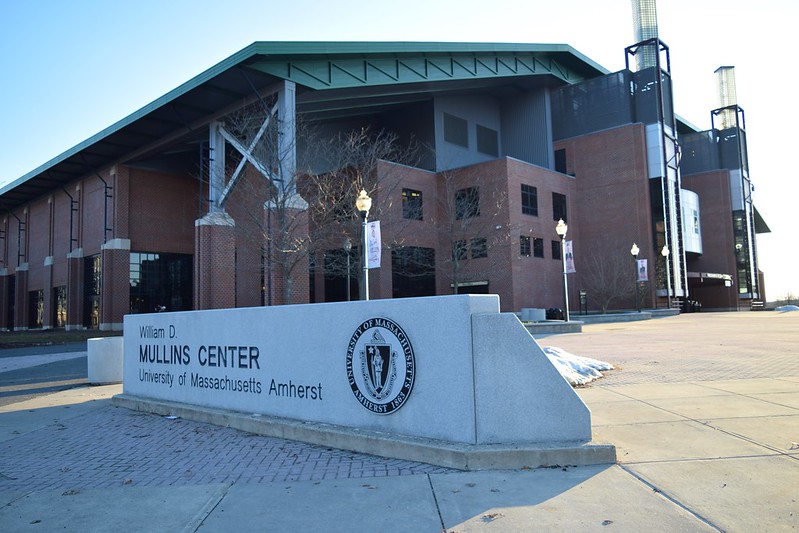

Long lines at the Mullins Center might have previously signaled a marquee hockey matchup against Providence College or Northeastern University. Now, they’re the symbol of the University of Massachusetts community buckling down on testing protocols in an effort to stem the mainly off-campus spread of COVID-19.

Testing at the Mullins Center’s Public Health Promotion Center has been free for UMass students since Aug. 6, and those living in the Amherst-area have been encouraged to get tested twice weekly since arriving for the school year. But in recent weeks, as UMass’ share of positive test results jumped sharply and then leveled off, the school has put additional emphasis on asking students to get tested often.

On Sept. 28, the UMass community was abuzz with the news from the previous Friday that a small cluster of cases that had spread from an off-campus party.

That Monday, Boyd, Hoey and the rest of the PHPC staff tested over 3,000 people, their first time of the year eclipsing that mark in a single day. By Wednesday, the results were in — 28 more students had tested positive for the virus.

The following Monday, the PHPC recorded 3,217 tests. “It was pretty nonstop all day,” said Boyd, who saw the rush firsthand from her post in the testing center.

With UMass now asking all students in the Amherst area to get tested twice weekly, as opposed to merely encouraging it, PHPC workers are seeing more students who haven’t yet visited the testing center.

“We’ve been getting some new people coming in,” Boyd said. “When we ask, ‘Have you been here before,’ there’s been a fair amount of people who say it’s their first time.”

For Boyd, Hoey and other nursing students, working in the PHPC is akin to a class. In any other year, they’d log multiple shifts per week in local hospitals to hit graduation requirements for clinical credit — time spent in a hands-on learning environment. Hoey said that for one class, he needs to complete 156 clinical hours.

“This semester, it’s been tough to actually get those assignments because some hospitals aren’t taking students or they’re limiting the number of students,” Hoey said.

The nursing majors now work only one 12-hour shift each week at a local medical center — many go to Cooley Dickinson Hospital in Northampton — and fill in their remaining required hours with one-to-two shifts per week at the PHPC.

Since the testing center opened in early August, it’s been staffed by nursing students, University Health Services employees and other workers hired specifically to manage the facility.

Based on information the school was providing over the summer, “We knew that we were going to be playing a role in the testing from the end of the summer,” Hoey said. When school administrators told them that they’d be staffing the PHPC to make up for lost clinical hours, the students were given an opportunity to explain any extenuating circumstances that would keep them from working, Boyd said.

Being on UMass’ front lines is “a little nerve racking,” Hoey said. He and the other nursing students have in-person academic requirements that they’ll need to complete to graduate. If the campus fully closes or if students are sent home, that could affect their graduation timeline.

“We’re all paying attention to the numbers,” Hoey said. “Nursing students and anyone else who has things that are required to be in-person, we really don’t want those things to get canceled.”

Hoey said that prior to the semester, his family was concerned about him working in a hospital during the pandemic. But they’re less worried about him working at the school’s testing center, he said. Instead, their worry is that of many parents of UMass students — that they might bring the virus home.

But both Hoey and Boyd said that they feel safe working at the testing center. They’re tested twice weekly, the same as any other UMass student with an in-person class.

If they’re checking people in at the entrance or observing the nasal swabbing, the workers are behind a panel of glass. When not behind the glass, they wear face shields or goggles. Everyone dons a mask at all times, regardless of which station they’re assigned to.

For an intricate process that requires getting several thousand tests to a lab in Cambridge each day, the Mullins Center testing operation is surprisingly simple.

People queue up at the Mullins Center’s northern entrance. Once inside they’re directed to a sign-in booth, where they’re asked a few identifying questions and then provided with a small test tube and a cotton swab. They proceed around the stadium’s concourse until they’re directed to an open testing booth. They swab the inside of their nose, place the sample in the test tube, sanitize and leave.

What most people don’t see is the staff checking to make sure each test tube has a working label, so that samples can be identified with the person who provided them once the test is run. But beyond that, “It’s pretty straightforward,” Boyd said. “What you see is what’s going on.”

Will Katcher can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter at @will_katcher.