The W.E.B. Du Bois Library towers over the University of Massachusetts campus at 28 stories tall, an icon of the University’s skyline. Housed on the 25th floor is a collection of over 100,000 items from the life of the library’s namesake: William Edward Burghardt Du Bois.

Although the library was not named for Du Bois until 1994, the collection of his historical documents has been kept at UMass since 1973. How the Du Bois papers came to UMass is a tale involving long negotiations, international travel and anti-communist opposition.

Born in 1868 in Great Barrington, Du Bois became a civil rights scholar, writer and activist and founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He spent his life keeping and curating his own primary source materials. The many pieces of his writing, poetry and even childhood thank-you notes eventually culminated in the prodigious collection that makes up the Du Bois papers. The collection illustrates the story of Du Bois’ life, from the broad political significance to the fine personal details.

“It’s a phenomenal look at the sort of the evidence of Du Bois’ movements – the way he thought about his career, the way he thought about his peers and what he was up to, politically, intellectually, throughout his long life,” said Adam Holmes, program manager at UMass’ W.E.B. Du Bois Center. “I mean, the richness of the letters alone would be enough to really give you a real sense of what’s going on Du Bois’ life.”

“I think what’s really wonderful though, about the papers, is the portrait they paint of Du Bois as a person that shows you the person behind the published books,” Holmes said. “Behind his enormous scholarly influence, you see him writing, asking about mundane things like, ‘can I please get paid for this lecture that I did’ or, ‘I’m claiming back expenses to the NAACP’ or negotiating delicate personal moments, whether it’s with peers or with members of his own family.”

“Both good and bad, these papers provide real insights into his personal existence.”

The Du Bois papers arrived at UMass in nearly five decades ago, but the story of their acquisition began years before, as described in an article by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, scholar in residence at UMass’ W.E.B. Du Bois Center.

In 1961, the Du Bois family moved to Ghana with approximately one-third of Du Bois’ collection. Another third went to historian and Communist Party leader Herbert Aptheker’s home in Brooklyn, New York. The final third was given to Du Bois’ alma mater, Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. It remains in the Fisk library to this day.

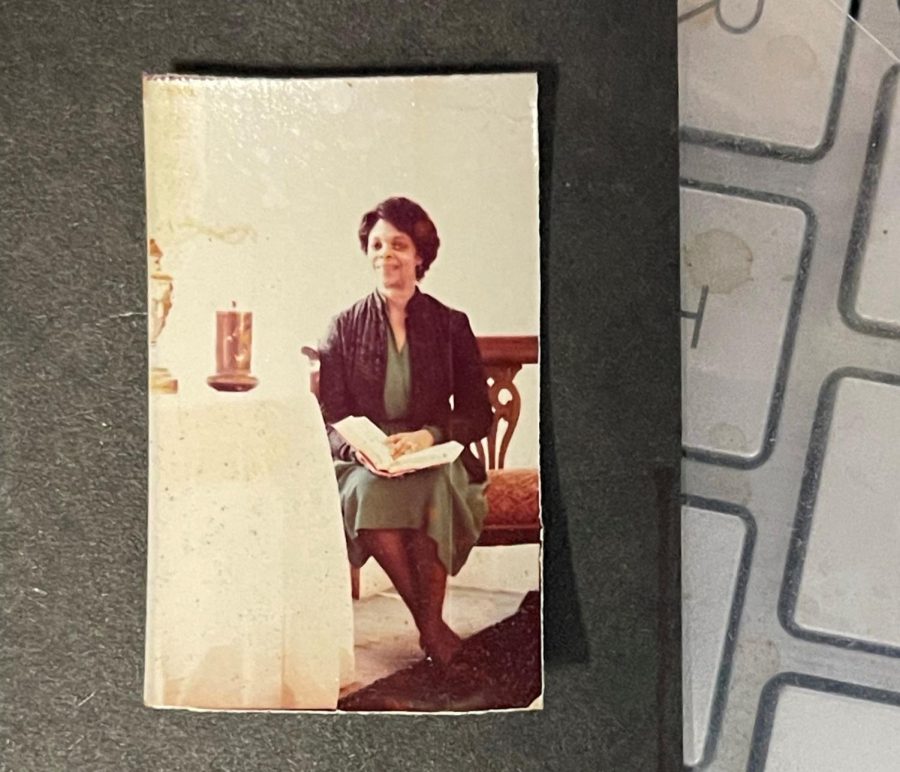

Du Bois left the fate of his collection to his second wife, activist Shirley Graham Du Bois, writing in a 1952 letter, “Please talk to Shirley Graham on matters concerning my books and papers. She has complete charge of their eventual disposition.” Graham was instrumental in the preservation of Du Bois’ collection. She spent decades of her life organizing the papers, advocating for the preservation of Du Bois’ legacy as an activist and ultimately publishing two studies on Du Bois. Graham received an honorary doctorate from UMass in 1973 and taught in the Afro-American studies department for two years.

In the 1970s, Randolph Bromery, the Amherst campus’ first African-American chancellor and a former Tuskegee Airman, began strategizing how to bring the collection to Du Bois’ home of Western Massachusetts. An established scholar himself, Bromery wanted to promote and preserve Du Bois’ legacy as a Black activist, writer and scholar.

Jules Chametzky, professor emeritus of English and founder and co-editor of The Massachusetts Review, helped bring Du Bois’ papers to campus. One challenge Bromery and UMass faced in securing the papers was battling with other universities such as Harvard University, according to Chametzky.

“I think Skip Gates was in charge of the [Center for African and African American Research] Department at that time, and he thought Harvard should get the papers there because Du Bois had a scholarship given to him by Harvard,” said Chametzky.

Another challenge facing Bromery and UMass was dissent from anti-communist groups in Western Massachusetts, such as the American Legion. Du Bois was a member of the Communist Party, joining in 1961 at age 93, after moving to Ghana.

“You gotta contemplate why a man as intelligent as W.E.B. Du Bois would join the Communist Party even when it was on the decline in America,” said Chametzky. “Why such an intelligent man, being a Black man – the answer is pretty obvious. He was very disillusioned with American treatment of African Americans, so, you know, it was a gesture, it was a symbolic gesture.”

Despite pushback from anti-communist supporters, Bromery pushed forward with his mission to bring the papers to UMass.

“In the years that Bromery was working to bring his papers to UMass, [Du Bois] still had that stigma of being labeled a communist in this country, and I think that led to scholars and intellectuals at all sort of levels in all places not really giving voices to his work and the impact of his writings, and also just the impact that he had personally,” said Aaron Rubinstein, head of Special Collections and University Archives. “So, I think Bromery was definitely keyed into that and saw the importance of preserving and celebrating Du Bois.”

Ultimately, Bromery was able to purchase the papers for $150,000 after a series of meetings with Graham, Aptheker and Graham’s lawyer Bernard Jaffe in Cairo, Egypt. Bromery promised Graham that the collection would be stored on the 25th floor of the library, from where, he claimed, “If it weren’t for the curvature of the earth you could almost see Great Barrington.”

The papers were made available to scholars in September 1980, after almost seven years of sorting and organization. Today, the Du Bois papers are housed in the Special Collections and University Archives department of the library.

“Du Bois is actually sort of the inspiration in a lot of ways for everything that we do in Special Collections,” Rubinstein said.

The collection, accessible by request, remains impactful for visitors and students. Rubinstein says being able to physically hold Du Bois’ papers helps foster a special connection between the past and the present for those who access the collection.

“I think it’s that connection between understanding the history and the experiences of people like Du Bois,” he said. “Understanding what he wrestled with, how he thought through it, how he reacted to it, how he evolved as a person and as a thinker and organizer over time and being able to learn from those experiences and use those to both understand their own history but also use it as a tool and as an inspiration to engage with the world to make positive change.”

Though most of the works in the collection are almost a century old or older, Holmes says their messages and meanings are still relevant and important.

“Their relevance today is incredible, and is so informative as well, because what they show you is that these issues that we’re grappling with now, whether it’s about socioeconomic inequality, whether it’s issues of class, issues of the repression of socialism and communism, and of course, issues of race and racism and systemic racism, these are long stories that have, you know, a great foundation in American history going right back to our founding.” said Holmes. “Du Bois kind of exposes that throughout his career, and his papers allow us to see his exploration of these topics that have an enormous relevance today.”

The W.E.B. Du Bois Center holds “Breakfast with Du Bois” on Mondays, where students, staff, faculty and community members read and interpret different texts from the archive.

“The thing we do always at the Du Bois Center is seek to remind people that Du Bois can provide a framework, both intellectual and kind of moral, for thinking about our own time, and that the papers are a great resource in that mission,” said Holmes.

Ana Pietrewicz is an assistant Op/Ed editor and can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @anapietrewicz.