The recent events that unfolded in Afghanistan catalyzed a serious reflection on the United States’ general foreign policy across the board. For decades, the question of ‘what do we do in Afghanistan?’ has, rather strangely, bemused and befuddled policymakers with their weighty PhDs. Do we give more funding to the military? Do we withdraw troops? Do we practice ‘nation-building?’

In my eyes, the answer is simple: don’t do any of that.

Post-WWII, American policymakers have not bothered contextualizing policy with the present state of affairs; The same chain of logic that worked in Second World War does not work in every situation. During WWII, there was a clearly defined enemy, a clearly defined cause for war and a clearly defined method of attack.

Then came Henry Kissinger. Kissinger, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, graduated with his BA and PhD from Harvard University and went on to carve a career in the public sphere. He worked as a political advisor for multiple presidents and eventually became Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon and Vice President Gerald Ford.

Kissinger’s approach to foreign policy was defined by realpolitik, a political model based on practicality and self-interest of the state rather than moral and ethical concerns. To put it simply, the U.S. was the primary actor in the international arena, while every other nation was a piece that may or may not have fit into the puzzle at any given time.

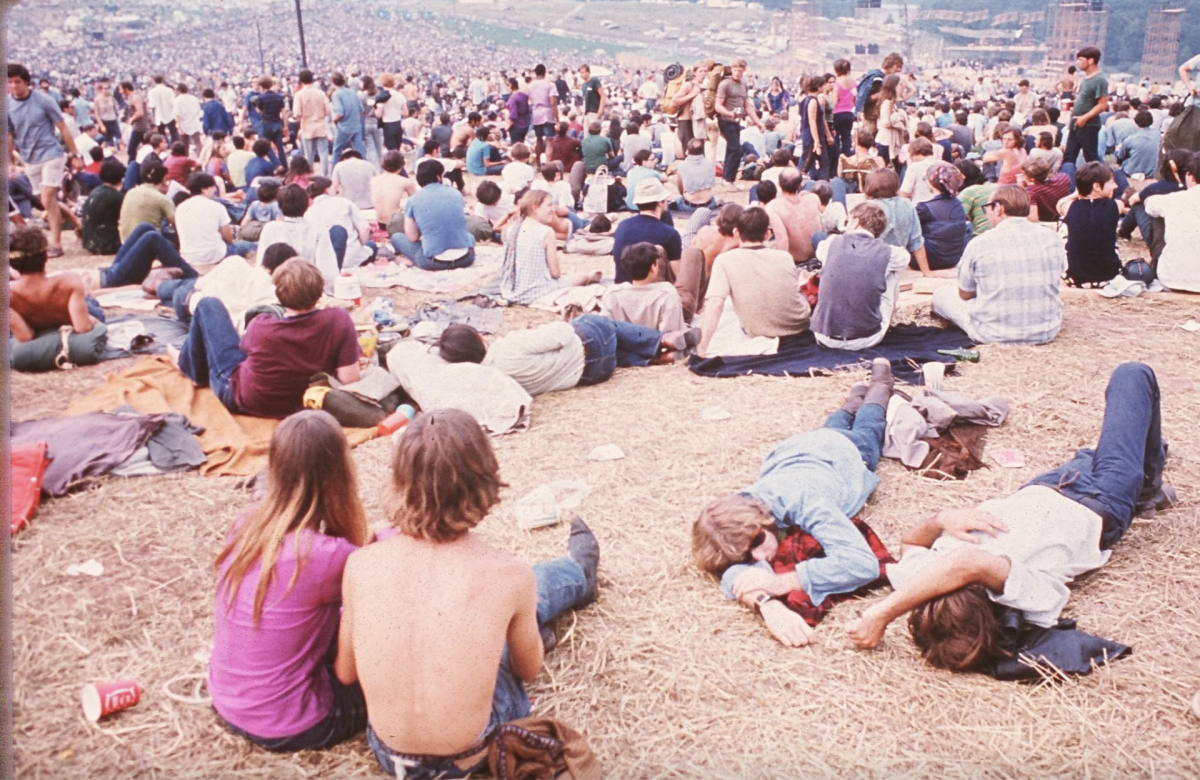

This model of foreign policy and international relations was perhaps most applicable during the Vietnam War. American intervention in Vietnamese affairs was substantiated by a very crudely defined premise rooted in realpolitik, called the domino theory. This theory states that if one non-communist state were to fall to communist powers, nations in its immediate proximity would inevitably become communist as well.

Now, the idea of being anti-communist was not always considered malignant. After all, virtually every socialist state at the time had widespread issues of famine, corruption and loss of personal freedom. The modus operandi guiding the U.S. was direct and abrasive at its core. By trying to establish a foothold in Southeast Asia, the U.S. completely neglected local cultural norms, communities and the right Vietnamese civilians had to a just and peaceful existence.

Although the Vietnam War was perhaps the most prominent manifestation of American realpolitik-a-la-Kissinger, it was not the only one. The Chilean and Argentinian military juntas and controversial support for Pakistan in the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War are emblematic of American political realism.

For better or worse, this idea of national self-interest and chess-like policymaking has remained entrenched in the hallowed halls of Capitol Hill and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. In the twenty-first century, the United States has yet again attempted hasty and callous ‘nation-building’ as a legitimate premise for its intervention in foreign affairs. The initial intervention in Afghanistan post-9/11 was perhaps the most calculated foreign intervention in recent history, utilizing a few highly-trained Delta Force operators to establish ties with the Northern Alliance and understand the Taliban/Al-Qaeda’s motives.

Since then, countless lives have been lost in Afghanistan, Iraq among other places; unfortunately, many of which are a direct result of collateral damage. Thousands of valiant American troops have been sent in without any consideration of the present facts. If American policymakers sought to implement a bottom-up approach, or the understanding that both American and local actors are more than mere pawns on a chessboard, then many catastrophic situations could have been avoided.

As students, we may not immediately perceive the gravity of this situation – and that’s fine because we don’t have a hand in anything that’s going on right now. Many of our readers were born around or right after September 11, 2001, so the level of connection we have to modern American politics may not be as much as, say, our parents, first responders or veterans who experienced the weight of the tragedy first-hand. It is essential, however, to understand the ripple effect of global politics, even more so as an American, granted our nation’s prominence in international society.

It’s time that political scientists and policymakers get out of their textbooks and untested models and actually examine the ground reality. Theories and models are only meant to guide those making policies and not to act as an end. Understanding local culture, language, norms and precedents is how the US will create a symbiotic effect upon itself and the world. If America wants to return to its fundamental principles and truly be a paradigm of peace, liberty and justice, it must embrace reality instead of creating its own.

Anay Contractor is a Collegian columnist and can be reached at [email protected].