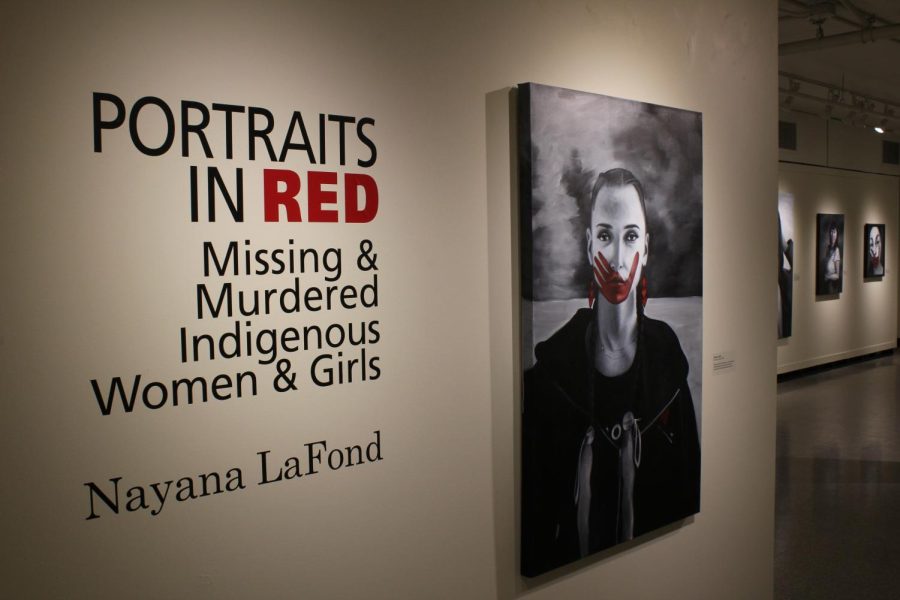

Spread across all four walls of the Augusta Savage Gallery are the piercing eyes of women forgotten by America. They are the victims, survivors and activists of a violent epidemic plaguing Indigenous women in the U.S. Local artist Nayana LaFond seeks to illuminate this issue with the spring exhibit, “Portraits in Red: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls,” at the University of Massachusetts.

LaFond paints portraits of Indigenous women who have been assaulted, abducted, murdered or are activists raising awareness for this crisis. Done in stark black and white acrylics, each painting has a distinct red handprint stamped on its canvas. The gallery, located in New Africa House, is entirely dedicated to these portraits, specifically selected by the artist for this exhibit.

Four out of five Native women experience violence during their lifetime, but these instances remain severely underreported. Of 5,712 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls — a lower-bound estimate — 116 were officially recorded by the Department of Justice. These cases also receive little to no media attention. Of the 506 cases reviewed by the Urban Indian Health Institute, 95 percent were never covered in a national news outlet.

“[LaFond’s] honoring a spectrum of people that are involved in this issue,” said Alexia Cota, associate director of the Augusta Savage Gallery.

LaFond’s portraits allow the woman portrayed to exist in all her complexity, and resist reducing the individual to another statistical data point. Each portrait is accompanied by the subject’s story, as told by their family, except for two anonymous paintings. As of January 2023, she created 108 portraits.

Cota was drawn to the indirect gaze found in the painting “Karen in RED.” The subject is looking away from the viewer and set against a dark background. “There’s a minimal amount of light on the canvas and so it’s really striking when you see it,” she said.

“Portraits communicate a lot of emotion,” Lily Harris-Hendry, a junior political science major, said. When touring the exhibit, use of color stood out to her.

“I hadn’t heard of the artist before, and it was a very deeply political topic. I haven’t really seen any art about Indigenous women before that,” Harris-Hendry said. “It was very revealing.”

LaFond began the project in 2020 after she posted the painting, “Lauraina in RED.” The portrait was widely received on social media and LaFond offered to paint portraits of women and people involved in the crisis.

Families and friends began reaching out with their stories and favorite images of their loved ones. The requests are continuous, and LaFond remains committed to painting each one. Often, the reference image is a selfie taken by the subject, an untraditional perspective for a formal portrait, Cota noted. “These are all angles we’ve all taken photos from,” she said. “Almost like they were giving us this photo to remember them by.”

LaFond’s art rarely focused on portraiture painting prior to undertaking this project. For Cota, her mastery of the medium is clear. “Nayana paints eyes so incredibly. You really feel like you understand them,” she said. “You almost feel like you recognize someone in them.”

Homicide is the third-leading cause of death among Native women under 24 years-old, according to the Center for Disease Control. This is true of no other demographic group’s data. In comparison to the national average, Indigenous women are 10 times more likely to be murdered.

For a crisis so pervasive and entrenched in history, art can be an effective advocate.

“If you watch television news, you know you’re going to get a certain viewpoint,” Cota said. “People have a way of putting a wall up depending on where they are getting their information.”

Art, she said, has a way of sneaking through those boundaries. “It can open you up in a way that you might not expect,” Cota said. “You can relate to it… It has a way of communicating almost a lot quicker than when language is being used. Which means it can have a very, very positive effect on people.”

Grace Fiori can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter, @grace_fiori.