1983-86: Arsons, Lawsuits and Alleged Racial Discrimination

In the fall semester of 1983, a series of fires plagued the University of Massachusetts campus.

By Dec. 1, there had been over 40 cases of arson in the dormitories, including 16 in Crampton Hall alone, ranging from bathrooms and bulletin boards to student bedrooms.

These fires garnered national media attention. The campus reeled as the district attorney’s office started an investigation to identify the arsonist. The undergraduate student government established a “Student Network United to Fight Fires Fund” through community donations that offered a reward for any information leading to an arrest. Requests were made by the vice chancellor for student affairs for faculty to consider delaying assignment deadlines and exams for students in Crampton Hall. A petition was signed by 131 dorm residents asking the University to fully refund the housing fee.

As a residential assistant in Crampton, Yvette Henry was in her room when police came by in the early evening of Friday, Dec. 2. Henry, a 20-year-old senior studying chemistry, was taken by authorities to the police station, where she was questioned for nearly three hours before being arrested, according to a New York Times article.

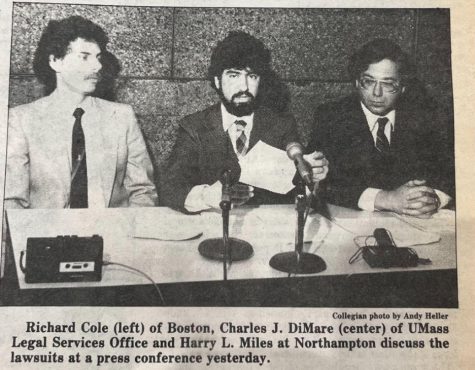

Thelma Griffith Johnson, the then-director of affirmative action at UMass, told the Collegian at the time that when she arrived at the station, she “could hear her crying.” Johnson made the request for Henry to contact her mother in Philadelphia before she called Charles DiMare, the Legal Services Office attorney, who arrived to serve as Henry’s counsel.

Henry’s cash bail was set at $10,000; she would later be released after posting $1,000, which was partially raised by students in her dorm.

Henry’s arrest, as well as the identities of the other potential suspects, were met with outrage by the student body. All student suspects, including Henry, were Black. Michael Pill, another attorney at the Legal Services Office, told the Collegian that there was “a history of race relations problems with some police on this campus, and we have had complaints in this case related to that.”

Henry would be suspended and barred from campus immediately following her arrest, with then-Chancellor Joseph Duffy stating that “the campus must have the authority to suspend anyone whose actions are a threat to the community.”

By Dec. 23, just over three weeks after her arrest, all charges against Henry were dropped for lack of evidence.

On May 7, 1984, DiMare announced that Henry would be filing two suits in the U.S. District Court in Springfield. The suits, totaling nearly $13 million, named the University, the Massachusetts State Police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation among more than 20 defendants. In addition to the compensation, Henry’s suit sought to forbid the release of any records of the investigation and its erasure from her academic record.

The suit alleged that Henry’s arrest was based on “racial considerations in connection with a psychological profile compiled by the FBI.” According to Henry, she was “induced by trickery and deceit” to accompany officers to a trailer near the station, where she was held and questioned for three hours without counsel.

Northwestern District Attorney W. Michael Ryan told the Collegian in a 1984 article that the FBI felt that “if we let this woman go, the best she would do would be to commit suicide…and take a good portion of UMass with her.” The Bureau also informed investigators that they believed that they “may have another Jonestown,” referencing a doomsday cult that committed mass murder in the late 1970s.

According to Rosemary Tarantino, the assistant district attorney, they were considering a “psychiatric examination” for Henry.

United Press International wrote at the time that Henry alleged that her arrest was based on an FBI profile detailing her as a “Third World woman who was probably severely depressed.”

Henry would later settle with the University.

Henry’s arrest would continue to reverberate around UMass when, following the 1987 World Series, a series of racially-provoked brawls broke out on campus. An independent investigation was launched by Chancellor Duffy that found “a distrust of campus police and the Dean of Students’ Office based in large part upon their handling of the Yvette Henry case.”

The report added that because the charges were dropped and Henry’s suit was settled out of court, the community never had a chance for a “full and public airing of the case.” The investigator noted that he suspected that “the administration grossly underestimates the bitter residue that has resulted from this case.”

1986 to 1993: SLSO versus the Board of Trustees

On July 17, 1986, the Board of Trustees voted to rescind the power of UMass Legal Services Office to sue the University on behalf of students.

The Board argued that the right to litigate against the University caused “hostility between the office and University staff, and increased difficulty in obtaining liability insurance,” according to a 1986 Collegian article.

Charles DiMare, who had previously co-represented Henry in her suits, estimated that 20 percent of the LSO cases involved “students versus the University.” The article also explained that the Amherst student trustee, Dani Burgess, believed that the insurance liability argument was “bogus” and that a vice chancellor had described the change as “nothing more than a vehicle to remove the right to sue.”

Following the vote, a group of students filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court in Boston asking to return LSO to full power.

In the suit, the students argued that LSO services constituted a public forum. They cited Cornelius v. NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc., which held that “a state government may not restrict access to a public forum without the requisite governmental interest.” Additionally, they argued that the University’s actions were a form of “content-based restriction” of their First Amendment rights.

The Court’s conclusion found that “although the LSO provided a vehicle through which UMass students expressed themselves, it was not a traditional public forum and the University had the right to regulate access to its services and, indeed, eliminate the forum entirely.” Furthermore, the Court stated that “the rescission of both services, granted together, was content-neutral, and did not violate the UMass students’ First Amendment rights.”

The students appealed the ruling to the U.S. First Circuit Court of Appeals, who affirmed the lower court’s decision.

On Aug. 31, 1987, the Board voted to strip all power from the Legal Services Office. The motion stated that “attorneys and staff in the center shall not engage in, not assist in engaging in, any litigation of any kind before any court or agency, provided, however, that such attorneys may refer any matter requiring litigation to outside counsel.”

Communications between the Board have been obtained by the Collegian that detail their SLSO decision. In a letter between Michael Hooker, then-President of the University system, to the Board of Trustees, the vote was recommended by Trustee Lawrence DiCara after visiting campus. DiCara informed Hooker that UMass “does not belong in litigation business” and as such, LSO should be “restructured” so that it would have no litigation authority. DiCara also emphasized that LSO attorneys should be under “University line authority as long as they are University employees.”

Student government officials told the Collegian at the time that they believed the motion was “designed to help the trustees’ court case.” Then-SGA President Joe Demeo noted that the motion particularly denied access to students who could not afford private practice fees.

1993 to 2010: Limited Litigation and Reauthorization

The power to litigate would not return to LSO, now Student Legal Services Office (SLSO), until 1993 when the Trustees voted to reauthorize their litigation ability. In “Doc. T93-059, Addendum 1,” the official document from an executive committee meeting in November 1993, the Board explained that while SLSO could return to litigation, it would be limited in its authority.

SLSO could not “provide representation in litigation against the Commonwealth or any of its agencies, subdivisions or instrumentalities” including the University, “or any municipality, or against any officer, trustee, agent or employee of these governmental entities for actions related to their official duties or responsibilities” — a policy similar to the one in 1986.

Additionally, the document required a review of SLSO by the president of the UMass system and the UMass chancellor. This review had to include “the number and types of matters handled, the number of students receiving assistance, the financial need of those students on whose behalf litigation was commenced and any fee structure put in place for students on whose behalf litigation has been commenced.”

The document also included a “sunset provision” which granted reauthorization for a “two-year trial basis” and was scheduled to expire in 1995.

Further documents obtained by the Collegian between then-Chancellor David Scott and other administrative officials detail the SLSO review. Scott explained that SLSO’s two-year period was successful, noting that between 1993 and 1994, SLSO oversaw 3,000-plus advice and referral cases. In a letter to then-Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs F. Javier Cevallos, Scott explained that SLSO provides a “valuable” service to students. He added that SLSO “particularly strives to assist students in resolving problems for which it would be difficult or impossible to obtain legal services at affordable prices.”

“In this way, SLSO helps the University accomplish its goal of student retention and enhancing the quality of students’ experiences on this campus,” Scott said.

The sunset provision would not end when SLSO was re-approved in 1995. The Board required that SLSO was to be reviewed again in 2000 and in 2010, to which it was re-approved both times.

Present Day: The role of the SLSO

Bernadette Stark has been the director of the Student Legal Services office since 2019. She previously served as a senior staff attorney with the office between 2008 and 2010.

A first-generation student, Attorney Stark has always prioritized legal access to those who needed it most. “I experienced many of the barriers to matriculating that many other students are still facing to this day,” Stark said. “I want to be helpful by removing as many of them as possible.”

Stark sees access to legal services as a social justice issue. “Our court system is largely skewed in favor of those who have financial resources,” she explained. “There are so many legal barriers that have nothing to do with the behavior of the person.”

The office continues to play a significant role in social justice movements across campus. “One of the functions that we provide is legal information and education from matters ranging from DEI to student’s rights to protest,” Stark noted.

“We can play a vital role in these movements by giving those working on these issues with the legal background to do their work.”

“Generally speaking, we are trying to remove the legal barriers to education as much as we can,” Stark said. “Much of the legal issues that students face can originate from socio-economic factors and we try to address that through the legal system for them.”

In addition to accessibility, Stark is also guided by the educational opportunities that the legal services office can offer. “I came here because I wanted to work with students and assist them with their legal needs and educate them on their rights,” she said. “Some of the most important services that we provide is access to legal advice and education.”

The SLSO hosts educational programs on legal matters and also represents students in court, depending on the case.

The office offers an internship program, a rare opportunity for undergraduates. In addition to offering professional development and experience, the office works hard to embed its interns into the legal process.

While the scope of the office is wide-ranging, Stark pointed to housing assistance and international student support as major initiatives for them. In particular, she urges students to meet with SLSO to review lease agreements before signing.

Additionally, the office provides advice on visa issues, immigration petitions and temporary protective status for international students at UMass.

Stark also wants to reassure students that what they share with the office is strictly confidential. Except in the cases of imminent physical bodily harm, the office is bound by the rules of professional conduct.

“If you have something that you’re concerned with that might end up with the Dean of Students [or] police, come to us,” Stark urged. “We cannot and will not share any information that a student provides us with anyone at the University or outside the University, including the student’s parents.” Students can include their parents in the communications only if they waive such a privilege.

As per the authorization granted by the Board of Trustees, SLSO cannot represent students in criminal matters in addition to issues with state agencies such as the Department of Children and Families, the Registry of Motor Vehicles or the Department of Unemployment Assistance. While they can provide advice in these cases, the office often refers students to outside counsel for litigation, a policy that can be difficult when students cannot afford private attorneys.

Its legal functions are not directed in any way by the University administration, nor the Office of General Counsel for the University system.

Located on the ninth floor of the Campus Center, the office is open Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. during the semester, and from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. during winter and summer break.

Except in cases of emergency, SLSO only provides advice by appointment. To request assistance, students must complete and submit an intake form found on its website.

To be eligible for SLSO services, undergraduates must pay the Student Activities Fee and graduate students must pay the Graduate Student Senate Fee. Students enrolled in courses through Continuing Education or University Without Walls that do not pay their respective fees are not eligible.

The Future of SLSO

While providing UMass students with legal representation and advice, SLSO has also had to renew its fight for reauthorization. Since 2019, the office and Attorney Stark have been working to renew their limited litigation authority.

In May 2020, a program review board was created by the Board and the Office of General Counsel to evaluate the office and make recommendations for improving its performance. Overseen by Brandi Hephner LaBanc, the former vice chancellor for Student Affairs and Campus Life, the board consisted of Douglas Lewis, director of Student Legal Services at the University of Michigan, and Francina L. Muse, the director of Carolina Student Legal Services, Inc. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Joining them during their investigation was Patricia Cardoso-Erase, UMass’s associate dean of Students for Conduct and Compliance.

According to their report, obtained by the Collegian, the reviewers found four main issues relating to SLSO, including “the imminent threat of losing the authority to litigate cases on behalf of students” if reauthorization was not granted.

Concerns from the Office of General Counsel regarding reauthorization were detailed in the report surrounding legal authority, conflict of interest, liability and supervision.

The report cited the Henry suit, explaining that it was the last case where SLSO litigated against the University. It also stated that the actions taken by the Board in 1986 and 1987 were a result of Henry’s suit.

“The trustees and the program have had experiences over the years that resulted in a revocation of the program’s ‘litigation authority’. The last case in which SLSO or its predecessor litigated against the University was Yvette Henry in 1985.”

“As a result; In 1986, the Board of Trustees rescinded the authority of the office to represent students against the University and in criminal cases. Then, in 1987, the Trustees technically abolished the Legal Services Office, with no litigation authority.”

The report continues, “In 1993, as a result of lobbying efforts by student leaders, the Trustees voted to authorize limited litigation except in cases against the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, or any of its agencies, subdivisions or instrumentalities, including the University, any municipality, or any employees, officers, trustees or agents of these entities who are acting in their official capacities.”

It added that “there are some residual feelings or mistrust based on actions taken by the office in the distant past.”

The reviewers found that the Office of General Counsel viewed using “Commonwealth money” to advise against either the University or the Commonwealth as a “conflict of interest.”

They also found that students were “overwhelmingly in favor of SLSO representing students in criminal proceedings,” adding that students were “concerned especially for students of marginalized communities and international students being unrepresented in criminal court.”

It noted that between 2014 and 2019, SLSO saw an average of 126 students per year for criminal matters. The reviewers also met with local attorneys, who informed them that “there are very limited resources available for UMass students who are charged with a crime and cannot afford to retain legal counsel.” For example, there is no public defender’s office in Amherst.

As a result, the reviewers advise that “If the office ever obtains the ability to represent students in criminal matters, it would help the University’s retention goals, and the Commonwealth’s goals in ensuring access to justice for those charged with a crime.”

The Collegian reached out to the University and the Board for comment but did not receive a response.

The Board of Trustees also formed an “SLSO Litigation Re-Authorization Committee” alongside the review board.

SGA President Shayan Raza, a member of the committee, has been at the forefront of the process since the beginning of his term. Similarly to Attorney Stark, Raza explained that he views “access to adequate legal services as a human right.” As such, SLSO reauthorization is an “access to justice issue.”

As an agency, SLSO receives funding from the SGA to operate out of the Student Activity Trust Fund. Additionally, it helps to operate the conduct advising program, where the SGA attorney general hires and trains students alongside SLSO to assist students in conduct hearings with the Dean of Students office.

As a result, four senior members of the SGA (Raza, Vice President Meher Gandhi, Attorney General Afra Rindani and Patrick Collins, the chair of the Administrative Affairs committee) sit on the SLSOAC.

Following the reports, the Board of Trustees reauthorized limited litigation authority for SLSO for another ten years. T93-059 Addendum 3 was approved by the Board in December 2022 and will extend for another 10 years.

It reiterates that “the Office shall not engage in litigation either in court or before administrative agencies, against the Commonwealth or any of its agencies, subdivisions or instrumentalities including the University, or any municipality, or any officer, trustee, agent or employee of any of the foregoing for actions related to their official duties or responsibilities.”

Raza shared a letter that he wrote alongside GSS President Linet Preshma Pereira and Student Trustee Adam Lechowicz to President Meehan advocating for reauthorization. In it, they write that such services as immigration and housing law are essential and “set us apart from competing universities.”

“President Meehan, during our time at UMass Amherst, Chancellor Subbaswamy challenged us to be revolutionary – to be unwavering in our belief in our community and commitment to the values that have sustained this storied campus for more than 150 years,” they write. “As student leaders, we are reminded of your charge in your inspiring remembrance of the late Congressman John Lewis: ‘With his passing, we must […] energize and commit ourselves to the fight for fairness, opportunity and justice.’”

The letter concludes, “we can think of no better way to honor Congressman Lewis, Chancellor Subbaswamy and the spirit of this revolutionary campus than to protect students’ right to equal justice under law.”

Alex Genovese can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @alex_genovese1.