Massachusetts, one of few states with relatively low maternal mortality and morbidity rates, is in a difficult position. Upward trends in adverse pregnancy outcomes are pushing the conversation on solutions to address local and national obstacles within maternal health.

Part of this changing conversation can be told through prospective students and how they begin their education in healthcare. It relates to who they learn from, the relationships they build and how their personal experiences ultimately shape the care they are trained to provide.

Dr. Lucinda Canty, associate professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Massachusetts, expanded on factors which shape reproductive health outcomes and their impact on certain populations.

“When you think about pregnancy, our reproductive health represents our culture,” Canty said. “We know that the communities most impacted by disparities are communities of color. There is a connection when someone goes in and they see their provider, and the provider is from a community that’s similar to them or is from their community.”

While Massachusetts does not have any maternal healthcare “deserts” as defined by the nonprofit March of Dimes, maternal mortality and morbidity rates have steadily increased in recent years.

Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) refers to unexpected complications from labor and delivery, creating short- or long-term consequences for a birthing person’s overall health.

According to a July 2023 report from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, SMM rates nearly doubled from 52.3 per 10,000 deliveries in 2011 to 100.4 per 10,000 deliveries in 2020. Results from the study also revealed that Black non-Hispanic birthing people faced the highest rates of labor and delivery complications among all races and ethnicities.

After UMass Memorial Hospital in Leominster closed its inpatient maternity ward on Sept. 23 because of staffing shortages, community advocates voiced concerns about access to reproductive services in the area. Reporting from the Boston Globe notes that the maternity ward was the 11th to shut down in the state since 2010.

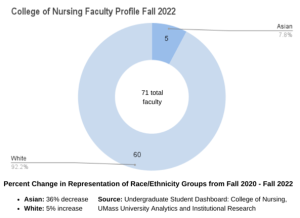

Dr. Favorite Iradukunda, assistant professor in the College of Nursing, draws attention to the loss of diversity as a symptom of staffing shortages in hospitals.

In 2022 alone, Massachusetts hospitals spent nearly $1.52 billion hiring temporary staff, with 77 percent of finances going towards temporary nurses.

Nurses on the labor and delivery floor spend a significant amount of time with patients from admission to discharge.

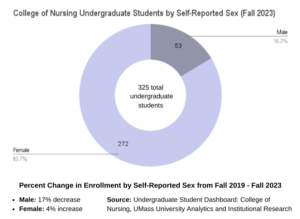

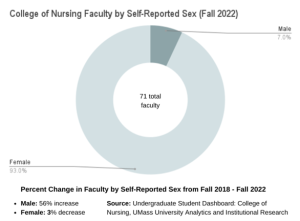

But what can diversity look and feel like in a profession historically dominated by white women?

At UMass, Canty and Iradukunda are beginning to spearhead initiatives to strengthen diversity within the nursing program.

Canty leads the Seedworks Health Equity Program, which provides mentorship opportunities and scholarships for nursing students from a variety of backgrounds.

“We’re starting to realize the need for diversity in nursing,” Canty said. “That’s not only based on race. That’s also based on religion, culture, [and] how people identify. We’re trying to create spaces where people feel like they belong because nursing is tough already. We don’t get enough education on an individual level to learn about other communities.”

Echoing these sentiments, Iradukunda’s research focuses on health outcomes for African diasporic women and birthing people. Iradukunda also helps with the Asian, Latino, African and Native American (ALANA) program in the College of Nursing.

“We’ve seen it in research where women have negative experiences [with] nurses, but we’ve also seen nurses advocate, especially Black and brown nurses,” Iradukunda said. “The [fewer] Black and brown nurses we have, the more women are exposed to not having someone to advocate for them.”

A responsive commitment to diversity is one solution Iradukunda believes will address the staffing shortage in nursing from the source – higher education – where students who wish to go into the profession should also be able to stay.

“As we talk about the nursing shortage, sometimes we talk as if we need a magical formula or some sort of extraordinary answer to address this issue,” Iradukunda said. “The only way to address the shortage, I believe, is to help people overcome those barriers, systemic barriers, and what stands between a person being able to access an education is resources.”

Iradukunda’s work as a nurse scholar is an example of holistic approaches to teaching in practice, looking at multicultural education to improve health in communities.

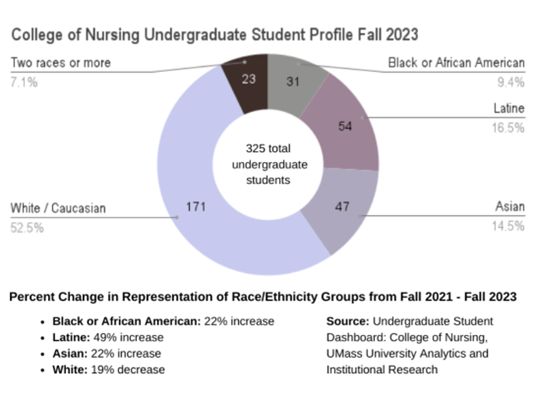

Demographic changes in Massachusetts signify an increase in diversity of the population within the past decade. Per state census data, the percentage of non-white residents in the state grew from 23.2 percent in 2010 to 31.4 percent in 2020.

Among the racial and ethnic groups who experienced the most change, Hispanic or Latino residents totaled 12.6 percent of the state population in 2020. Black or African American residents came in around 7 percent and Asian residents grew to 7.2 percent in 2020.

According to Iradukunda, a significant African diasporic population resides in Leominster and around the area in Worcester County. Central Massachusetts experienced the second-highest increase in Black and African American population growth from 2010 to 2020, and Hampshire County had the highest population growth at 55 percent from 2010 to 2020.

While the slight uptick in diversity is paving way for new notions of community, the need for healthcare workers that represent the populations they serve is more urgent than ever.

One example Iradukunda points to is rooted in the didactic coursework itself. Teaching a course titled “Cultural Diversity in Health and Illness” next spring, Iradukunda looks to challenge historically and culturally dated preconceptions of health.

Similar courses in the past focused on teaching concepts about various cultures, paired with a particular response “fit” to respond to patients from such communities. The focus now looks to increase accountability among healthcare providers, Iradukunda said, and identify how self-bias can impact the ability to accurately assess patient needs.

“I work with diasporic populations, [and] they have multiple cultures,” Iradukunda said. “We get the assumptions of how certain cultures are going to behave from research that was done in the colonial era. We built an entire response in healthcare based on something that should not have happened in the first place.”

“I work with diasporic populations, [and] they have multiple cultures,” Iradukunda said. “We get the assumptions of how certain cultures are going to behave from research that was done in the colonial era. We built an entire response in healthcare based on something that should not have happened in the first place.”

Student proximity to resources matters especially for the healthcare profession, where coursework is designed to be paired with hands-on application.

Another long-term goal for hospitals in the area is to develop a strong concentration of local graduates. UMass nursing students who are required to complete clinical rotations often choose Cooley Dickinson Hospital (CDH) in Northampton, which is part of the Mass General Brigham system.

Cooley Dickinson creates a pipeline for students who complete clinical rotations at the hospital into employment. Consequently, 47 percent of their new graduate nurses come from student placements. A new clinical match program launched this year is also furthering efforts to attract local talent.

“We find that often those students, if they’re from the area, stay,” said Lauren Grybko, director of Nursing and Professional Practice Education.

Cynthia Marlin is vice president of patient care and chief nursing officer at Cooley Dickinson. According to Marlin, the childbirth unit remains a unique focus area.

Programs created to allow nurses to train on the obstetrics floor is one of Cooley Dickinson’s strategies to optimize employment opportunities for recent graduates. As such, aspiring obstetrics (OB) nurses can gain a head start without having to complete two years of medical-surgical training beforehand.

“Healthcare is changing,” Marlin said. “The patients are changing; our patients are sicker. We’re seeing different types of situations [where] we need specialty nurses, OB nurses, maternity nurses, labor and delivery nurses.”

While the childbirth unit at Cooley Dickinson is fully staffed, Grybko does not turn a blind eye to circumstances nearby. Just three years prior, the birthing center in Holyoke permanently closed, bringing an influx of their nurses to CDH.

Grybko attributes the longevity of existing staff to the geographic connection that stems from training to employment. These strides, when combined with meaningful diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives are a sustainable path forward.

The distinction between recruitment and retention, said Iradukunda, transforms a student’s trajectory.

For Breanna Joseph, a biology senior on the pre-med track, involvement in the student-led organization Black Women in Medicine (BWM) bridged the gap between the availability of resources and her application. The group brings together students in pre-med, pre-dental, pre-physician assistant and nursing concentrations.

“Coming from my personal experience and the intersection of my identities, I tend to reach out to more racial minority communities,” Joseph said. “I have a big heart for women and for women’s’ health. That impacts the people that I’m looking to reach out to the most, serving the underserved, being underserved myself.”

The core ingredient to student success is not much different than the path towards creating equitable patient experiences.

As BWM’s community engagement director, Joseph shared that she identifies underserved populations and tailors teaching practices to empower the next generation of healthcare professionals.

“To me, it means grasping my education with two hands,” Joseph said. “And really reaffirming myself. It means looking at the people who are most affected by the health care disparities in the country and spotlighting them and taking priority to care for them.”