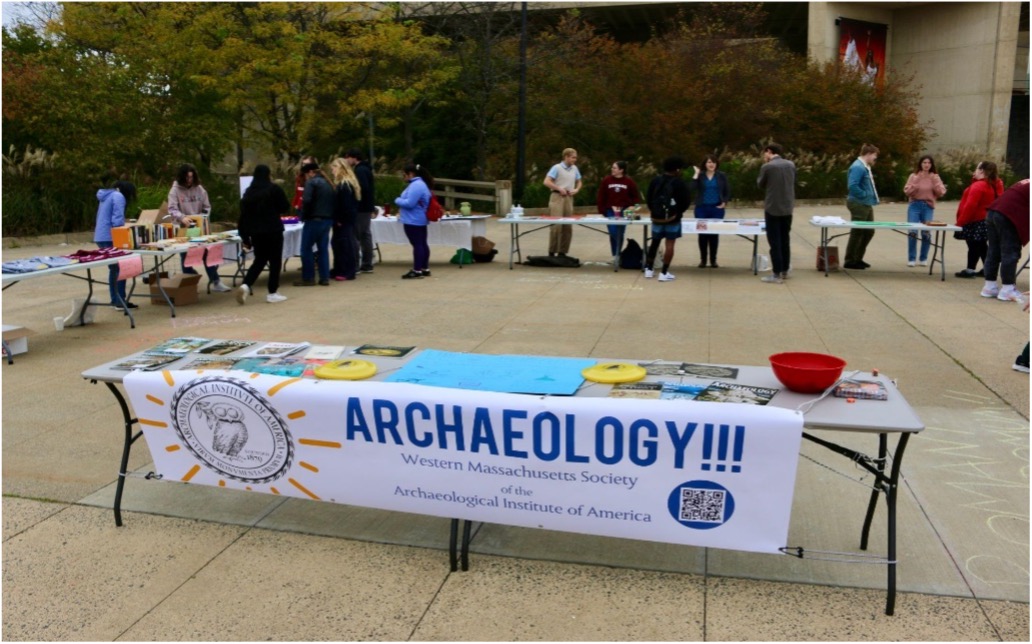

The Western Massachusetts Society of the Archaeological Institute of America hosted its International Archaeology Day Fair at the Bromery Arts Plaza outside the Fine Arts Center on Saturday, Oct. 14.

Visitors could travel into mankind’s past to learn about ancient civilizations and traditions with replicas of Roman coins, Greek pottery or digital recreations of archaeological sites.

“Learning about the past can tell us so much about both our future and our present, as well as everything about people and how they live,” junior psychology major Amelia Millstone said. “I feel like a lot of people tend to assume that people in history were so different from us, and that’s so not true.”

Millstone serves as the secretary of Eta Sigma Phi, UMass’ honor society for students studying Greek, Latin or classics. “We’ve always had music and art and all kinds of things like that. Because people have always been people, and there will always be people,” Millstone added.

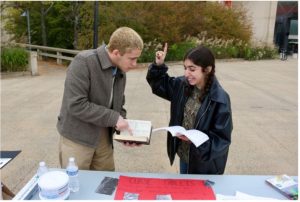

Millstone ran the event’s mosaics table, where students could make their own version of the ancient Roman art form. Starting with a paper template, visitors could use either colored markers or cut paper tiles to make their designs.

At another hands-on craft station, attendees could make their own curse tablets, similar to those made in ancient times. According to Mel Seraderian, a junior classics major, tablets are often made of lead, with etchings wishing misfortunes or bad health on one’s rivals. They were commonly buried upon completion, in hopes that the gods would receive a message.

When asked if there is any archaeological proof of the tablets working, Seraderian said, “The only effects that we maybe know about are the physical effects.”

According to her, some curse tablets were thrown in wells, which had disastrous effects on curse receivers.

A few steps away, attendees could view several ancient musical instruments such as the lyre, a handheld string instrument similar to a harp, or the aulos, an ancient Greek wind instrument.

Loren Isotalo, a senior double major in music and classics, performed live demonstrations of the aulos throughout the event.

“It’s very much like halfway between a recorder and an oboe because it has the double reed,” Isotalo said, describing the ancient instrument. “It’s very buzzy.”

According to Isotalo, ancient music is an important aspect of archaeology because even in ancient times, customs and traditions were expressed through music, many of which carry on in similar forms to the present day.

There’s a common misconception that modern archaeologists behave in the same ways as popular film characters — such as Indiana Jones — that undergo perilous adventures to acquire relics.

“You can ask literally any archaeologist ever and they will all say he is the worst one,” Isotalo said. “He doesn’t take any notes, he doesn’t record provenance information” … “Indiana Jones is super cool. And he’s the reason that a lot of the modern generations of people became archeologists, which is really cool. But in reality, we’re a lot more careful than that.”

While the actual field of archaeology may differ from its depiction in pop culture, there is still a lot of value and excitement to be found in the subject.

“Archaeology is really cool because it’s so worldwide, and you also get a lot of different people from different disciplines mixing [and] using computer knowledge and historical knowledge and language knowledge… People like to read about super cool things, and that’s how a lot of us get into it,” Isotalo said.

Computer-based archaeology was on full display at the event. One table, run by UMass’ Geographic Information Systems (GIS) librarian Becky Seifried, featured a map of human-made structures in the former town of Dana, now part of Petersham, Mass. In 1938 the town was disestablished alongside the creation of the Quabbin Reservoir.

Using Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology to create the map, laser pulses are sent out over the area for surveying. When the light from the laser reflects to the detector, the difference in time is recorded.

LiDAR is useful for mapping human-made structures such as stone walls, and for Dana, the laser can “see” through leaves in forests.

The fair display also included the archaeological site of Malthi, Greece. The site resided in the ancient region of Messenia, now part of the modern-day Peloponnese region. In the Bronze Age, a thriving community existed on the land, but over time was left to history. Rebecca Worsham, assistant professor in classical languages and literatures at Smith College, created a virtual recreation of the site with her students, which can be explored via Minecraft.

According to the project’s official write up, “These recreations draw on data from archaeological work at the site and are intended to depict alternative interpretations of the settlement, allowing for the uncertainty inherent in archaeology. They are likewise intended to invite interaction with the site beyond physically visiting, with the goal of increasing participation in the formation of knowledge about Malthi.”

The team created two versions of the Minecraft world. One for Java Edition, the most common version for PC players, and another for Bedrock Edition, commonly used on video game consoles. The world is open to the public and the Java Edition can be downloaded onto any interested player’s computer.

Nathan Legare can be reached at [email protected].