On Thursday, Oct. 26, Sonya Atalay, an Indigenous archaeologist and professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Massachusetts, spoke at the recent Distinguished Faculty Lecture about scientific research within Native American communities and the reclamation of traditional knowledge.

Atalay’s goal was to discuss the ways in which she created spaces to conduct research in reclaiming aspects of Native American culture and what she hopes to accomplish in the future.

“Institutions need to work on creating good relationships with Indigenous communities. Respect, reciprocity and ethics should be interconnected in all research,” Atalay said.

The Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences was where students could train in Community-Based Participatory Research, which includes collaborative research design, like sharing animation between story sharing and comics, she explained. The creation of animation and story sharing will allow Atalay’s research to reach a wide-ranged audience.

Her work of reclamation began following the establishment of the U.S. Federal NAGPRA law in 1990, which says, “Congress acknowledged that human remains and other cultural items in holdings or collections or removed from federal or tribal lands belong to lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.”

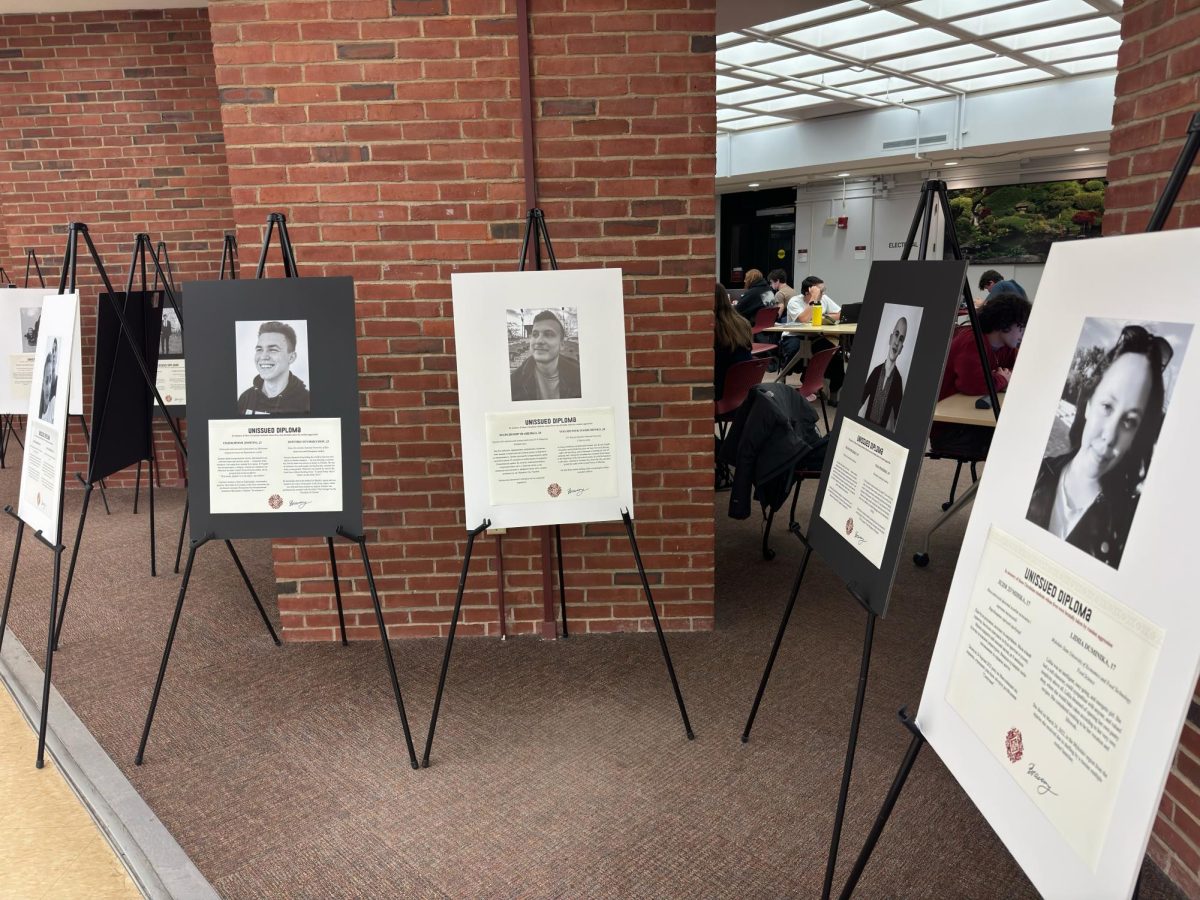

In 2006, Atalay participated in the repatriation of Native American ancestral remains at the University of Michigan, where 122 remains were being sorted through. Each body part had a number and “for hours I heard numbers [being] read…26543-2, 26543-8,” Atalay said.

“We were there to prepare these ancestors for repatriation…It’s the same in every repatriation [but] this time it takes our tribal teams eight days,” she said.

The excessive number of boxes and long hours of working were due to the division of body parts from the ancestors, who were 122 men, women, children and infants that were separated into 1260 pieces, Atalay explained.

The ancestors had come from the Fisher site, named after the man who lived there, instead of the ancestral tribes who lived there before. “Museum records indicate that Mr. Fisher and his neighbors kept many of the belongings,” Atalay said.

In 2007, a University of Michigan professor went against the NAGPRA laws and used ancestral bones for research. One of the notes attached to a bone written by a student said “Cool! A Foot!”

Further questions were asked to the university about where the contents from the labs were taken and it was found that the soil matrix had been dumped outside the lab door.

“I will never forget the violence of that quiet moment. The level of dehumanization…” Atalay said.

Atalay and her team partnered with several Native American nations to help complete their work of repatriation with the ancestral remains and “repatriation transformed the University of Michigan’s relationships with tribes,” she said.

Atalay’s work involving the intergenerational braiding of land-based knowledge is showcased with different camps being held in Maine. Started in June 2017, the camps were free and lasted one week.

“Participants used the research to tell stories of their homelands…the youth worked with their elders to create a ThingLink [to show all the work the students have done],” Atalay said.

Reclaiming as healing, sharing the stories of repatriation, voicing struggle and sharing trauma and collecting practices of the past are all missions that Atalay and her team spread through their research.

Sydney Martin, co-author of NAGPRA Comics’ first issue, told the story of these ancestors and the struggle to bring them home. “We need to remember [that] this will be your work,” she said.

The Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences’ goal is to eventually have eight hubs across the U.S.

“What are the seeds that come from repatriation and reclaiming that can gather use in the real world?” Atalay said.

Eva Maniatty can be reached at [email protected].