On April 11, in a lecture organized by Charli Carpenter, professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts, Judge Fausto Pocar discussed his experience sitting Judge ad hoc on a concluded case regarding Ukraine v. Russian Federation. Pocar also provided his insight into a pending case brought forth by Ukraine against Russia in February to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the judicial body of the United Nations (UN).

Pocar explained the first case, which began with Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014. The two major parts of this case were the Russian Federation’s violation of the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism (ICSFT) and their violation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD).

The first violation was regarding Ukraine’s claim that the Russian Federation was financing terrorism. Pocar explained the court’s responsibility to define “funding of terrorism” in the most limiting interpretation to not overstep its jurisdiction. The ICJ defined funds as assets of any kind, legal documents that deal with financial matters and more.

However, Pocar said, “[This] excludes the means used to commit the act of terrorism, including weapons…the means of combat, the means of war. But how can you say that weapons do not have a monetary value?”

“Nevertheless, that was the decision of the majority of the court,” he said.

Pocar also explained the claim made by Ukraine against the Russian Federation, that the latter allegedly supplied a missile to bomb Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, a civilian aircraft, in 2014, while it was flying over Ukraine.

“There was evidence in the case that the day before the event, there was a truck that transited the border between the Russian Federation and Ukraine…on the truck, there were three missiles,” he said. “The day after, there is evidence that the same truck went back to Russia and there are two missiles. Was that the missile that shot down the plane? Maybe. But this was not [allowed to be] discussed.”

Pocar explained that this would be an instance of directly supplying weapons rather than financially “aiding and abetting” terrorism. As that falls beyond the scope of the ICSFT, the court did not find that the Russian Federation had violated its obligations under these articles.

Ultimately, there was only one claim, regarding other attacks, amongst the five brought forth where the ICJ decided that the Russian Federation did not respect the ICSFT.

“You have a curious situation in which the court is dealing with cases that have a specific object, that have, in the background, the main dispute in the state, but the main dispute is not taken up,” he said.

Pocar also expressed his disappointment with the limitations of the ICJ.

“I say [this] not to criticize the court—although I criticized it in my dissent—but [so] that you may understand the court. The jurisdiction of the court is already limited by the needs of clauses for the acceptance [of both states involved.]”

“If the court goes a bit beyond what its jurisdiction is, nobody will accept it anymore,” Pocar continued. “So, in a way, it is a certain compromise made, saying, ‘we will not go beyond the case you bring.’”

“And, if no one comes,” he joked, “the judges will be jobless.”

The second violation in this case, the violation of the CERD, concerned the Russian Federation’s alleged discrimination and suppression of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainian communities in Crimea. Pocar specifically explained two main points.

First, he said that the Russian Federation was failing to uphold its obligations to protect education in Crimea that was conducted in the Tatar and Ukrainian languages.

“For a minority community’s education to not be conducted in its minority language—being cut in so large an extent—is a violation of the convention,” Pocar said.

Second, the Tatars parliamentary system, called Mejlis, was banned and branded as an extremist group by the Russian Federation. Ukraine argued that this suppressed their political expression and infringed upon their right to representation.

The court agreed that the Russian Federation violated CERD in both these manners. After seven years, the case was concluded on Jan. 31, 2024.

The pending case Pocar discussed next is currently ongoing, so he warned attendees that he could only speak of what was already public.

The Russian Federation claimed that Ukraine was committing genocide in the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine. Ukraine went to the ICJ to refute these claims, which is well within the ICJ’s jurisdiction.

What the court had a more difficult issue with, however, is determining if an aggression which violates international law, but is carried out to prevent an alleged genocide, is legal.

The ICJ decided that, despite the means of preventing genocide not being expressed in the convention, it implies that the means of prevention should be in conformity to international law.

Pocar then accepted questions from the audience, which consisted mostly of political science and legal studies students and faculty.

“You said that to incentivize member states to deliberate engagement to court, the ICJ narrows its focus on claims. But doesn’t this create a paradox? In rarely gaining jurisdiction, how can the ICJ be effective?” Yash Manuja, a first-year political science student, asked. “Has it not de-incentivized parties to engage?”

Pocar responded, “You take my point. There is a certain contradiction that when you have to really resolve a critical issue, you step back, so as not to create concern in states that you will go beyond.”

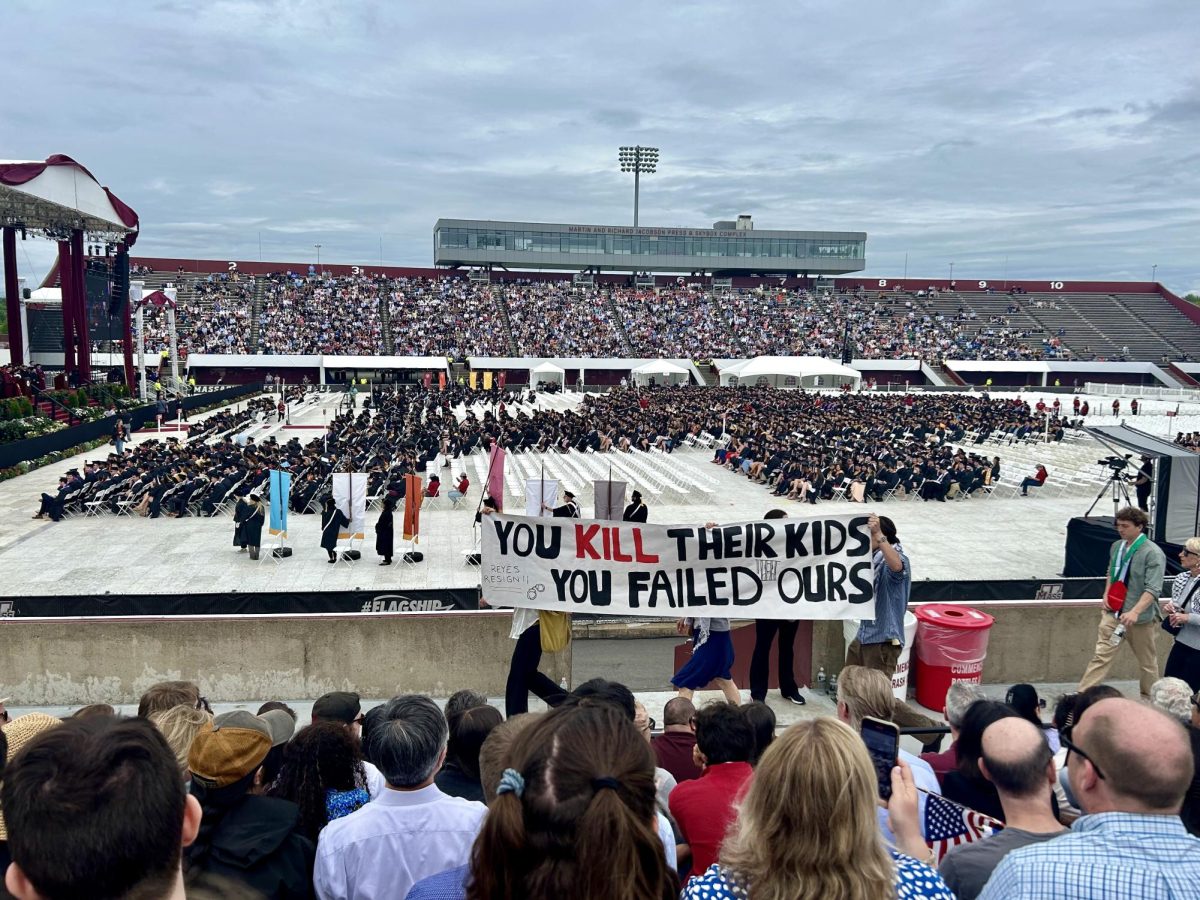

Pocar concluded by mentioning the current case against Israel, which he considered to be “more complicated than it was, even six months ago” and the case concerning states’ obligations to climate change.

Pocar anticipates that the court “may take a progressive approach.” This is because there are no boundaries regarding an assertion of the court’s opinion as to how states should act.

Senior psychology and political science student Isargy Delacruz said, “I thought [Pocar’s discussion] was very eye-opening. It was really nice to hear about the intricacies and complexities that go on within the court.”

“It just gives you a better insight about why things may not be moving as quickly as we hoped,” she continued. “It’s great to feel more informed.”

Kavya Sarathy can be reached at [email protected].