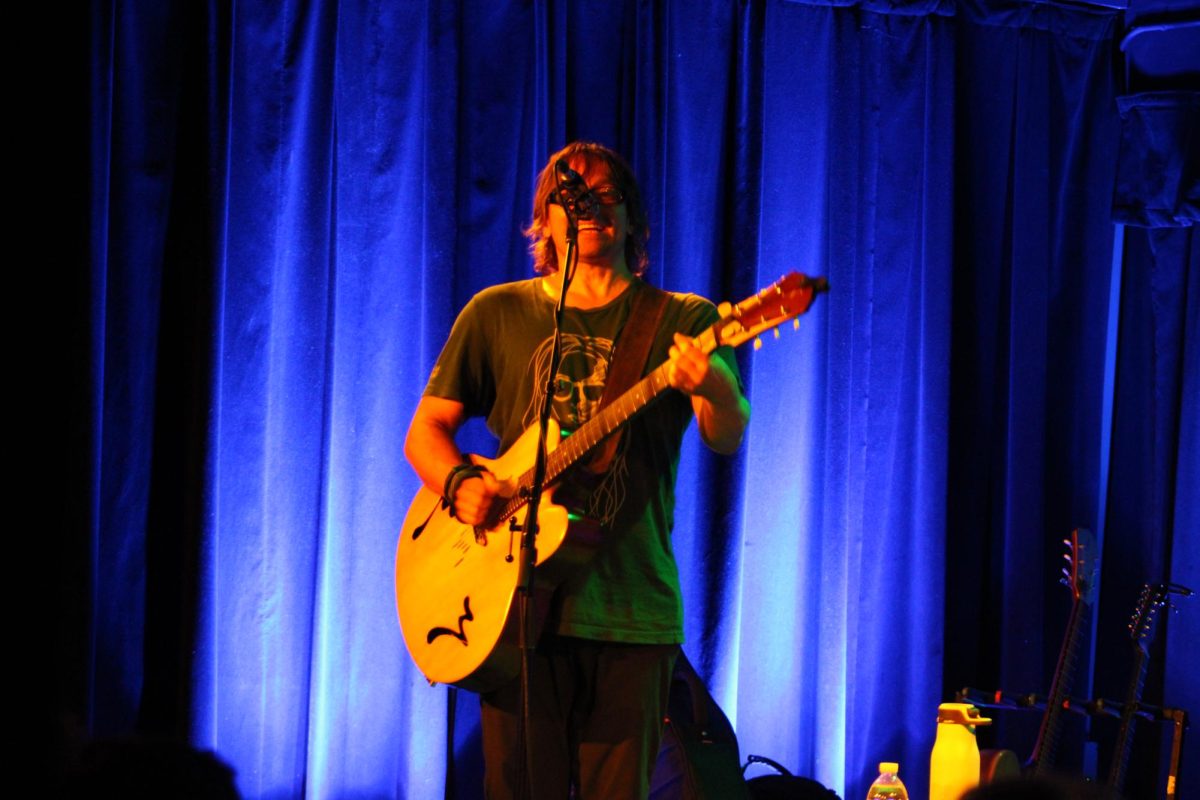

Singer and songwriter Bruce Cockburn is currently living on a high-note. Following the recent release of his 30th studio LP, the wonderful 2017 record “Bone on Bone,” Cockburn was added to the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame alongside Neil Young, Beau Dommage and Stéphane Venne.

On Nov. 7, Cockburn will bring his new record and his old classics to the Calvin Theater for what promises to be an exciting show. Prior to this show, Cockburn held a conversation with William Plotnick for an impassioned conversation about politics, the environment and the art of music. Check it out below:

William Plotnick: How are things going today in San Francisco?

Bruce Cockburn: Smokey! It’s clearing up a little in the last hour or so, but it’s pretty noticeable.

WP: While currently living in San Francisco, you’re witnessing the effects from the weekend’s tremendous forest fire. When asked in a past interview if you were optimistic or pessimistic regarding the current state of the environment, you claimed “I think we’re f**ked,” and that really summed things up. Your song, “If a Tree Falls,” deals directly with de-forestation and the environment as a whole. Is this past weekend’s forest fire a sign from nature that we are in fact quite f**ked?

BC: Well, I’m hesitant to assign more meaning to any particular event than it actually has. In general, I think that we’re going to be seeing more and more of this stuff in coming years because of global warming and because of changes in the weather that go along with global warming. It’s not strange [for] California to have forest fires during this time of the year. October is historically the worst month for that. But what is different about these fires is that the winds are gusting up to about 70 miles-per-hour and carrying those embers long distances that start new fires.

I’m not a meteorologist, but it seems to me that there is likely to be more of this unstable weather appearing on the scene than what we’re used to, and therefore all of these things are becoming less predictable and potentially more disastrous because of this unpredictability. You can’t really get ready for fires of this scale. The firefighters last night were running around trying to get people out of their homes. They have no time to actually be fighting the fire because they’re trying to rescue people. Some people were not even able to get out of their homes in time and some that did only made it out with minutes to spare.

California is a crazy place and it kind of always has been. If we start seeing fires like this in Minnesota, we’ll know we’re really in trouble. But in California, forest fires are part of its history to an extent. And often, it’s arson or accidental fires. Like the fire in Oregon just a few months ago, that some 15-year-old started letting out fireworks in the woods. In a certain way, that kind of stuff could happen in any era. I feel like it comes down to there being too many people, so the systems all break down. The educational systems break down and it’s too big a system to fully operate. You have some schools that don’t teach kids anything while other schools do. Some parents are so busy scuffling for their living that they don’t have the time to teach their kids or pay any attention to what they’re up to. So there’s always the risk that some kids are going to go off and do dumb things, or adults for that matter who do dumb things. It seems to me that everything is too big and too out of control and the efforts to control it are looking sinister because you can’t really control the real stuff—there’s not enough money or will around to fix education, so that everyone could be taught how to behave in a responsible manner. What you get instead of that is some sort of totalitarian control over people because that’s the cheap way to get it done. It’s a very complicated picture, and it’s one of the reasons why I said “we’re f**ked.”

But at the same time, I don’t feel completely hopeless about it. I feel the likelihood is that the human experiment is close to ending. But I don’t know that for sure and I hope that it isn’t true. I still have that hope. I’ve got a five-year-old daughter and I want her to grow up in a world that she can live in.

WP: You put it poetically in your memoir, “When I’m confronted by the degradation of our surroundings, I feel that freedom being threatened and eroded.”

BC: Yeah, there’s a sense of free space, even if it’s an illusion. In Canada, Margaret Atwood at one point years ago wrote a study of Canadian literature that kind of made the point that up to that time, Canadian literature involved tiny humans surrounded by big nature. You had the sense that we were confronted by an environment that was if not hostile, then disinterested in our welfare. That tone informed a lot of Canadian novel-writing and other forms of writing. That was a major element of life growing up in Canada, but the other side of that coin is that there was all this free space around us. You can always imagine that you can completely disappear into this free space and no one would care what you did. You could have lived on your own terms even if it was within your imagination. As you physically see that free space filling up, that option [of it existing within your imagination] goes away. So you’re forced to confront it, which is not an unhealthy thing because we should be looking reality in the eye. You’re forced to confront the fact that you don’t have that freedom — that you’re stuck in the circumstances that you’re in. I lament the loss of that free space — of that illusion of it, if it is an illusion. For me, throughout the first half of the 70s, it wasn’t really an illusion. I spent a lot of time on the road getting away from the stuff that urban society asks of you and that felt more free, whether it was or not.

WP: You’ve traveled all throughout the world, and you have had the opportunity to take in the expansive landscapes and environments that planet Earth has to offer. Do you think that there is anything that we can be doing throughout our daily lives to help make a positive impact on the current environmental crisis?

BC: That’s a good question, and it’s one I keep asking myself. I don’t know if I have a good answer for it. I think the small things we can do will probably count if enough of us do them. Vote for the people who have the right ideas and make sure you do vote. The idea that we should give up on democracy because it’s f**ked up anyway is a very mistaken idea. If you do that than that will be a self-fulfilling prophecy that will come true. People that want to be in power and want to exercise power over the rest of us are very happy to not have us vote and to not have us exercise our democratic rights. They’re always happy to kind of erode those rights and take them away. It goes with the territory. you have power and you want to have more power, you want to be able to get your job done more easily without having to consult with someone. Police are like that, military is like that and government is like that. So the only way to keep that from running away from us is by paying attention and exercising our democratic rights so people shouldn’t think that it doesn’t matter anymore. I feel like that happened in the last federal election here and I see it happening all the time. The hopeful bit was Bernie Sanders and his crowd and the very unhopeful bit was the way the Democratic Party sabotaged that. The fact that that happened doesn’t mean that we should just give up and turn our backs on it, because if you think things are looking scary right now then they’ll look a whole lot more scary if we give up our democracy.

WP: It’s nice to hear you say that because one can’t help but notice a tone of indifference among some young people today toward politics or what is taking place throughout the world.

BC: For sure, and I even get it. I’ve gone through periods of my life where I felt like it really wasn’t worth it. But, how much does it really take? This doesn’t mean you have to devote your entire life to working on this stuff. Just, when things come up, notice!

WP: Your songs “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” and “Radium Rain” deal with nuclear warfare. Nuclear warfare is an issue you have been a strong advocate against throughout your career. Do you view the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons winning the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize as a big step forward in this issue?

BC: Well, I think it’s appropriate, but I’m not sure how much that means in terms of reaching any goal. But it seems to me that we were closer to getting rid of nukes 20 years ago than we are now. But any positive attention that is paid to that issue is good.

WP: It’s gotten to the point that I’m afraid to check the news every day because two very powerful people both seem to be inciting one another to bring this kind of warfare about.

BC: As long as the weapons are around, the risk is there. Some idiot’s going to use them. You have this jerk in North Korea, posturing in the way he is. But he’s not without his reasons in a way, but it’s an irrational response to the reasons. Then you have this comparably irrational response coming from our side and it makes one nervous. And it’s not that I’ve never had to be nervous about this before—the threat has always been there. Coming of age in the ‘60s, you were very aware of it. There was the Cold War, the Cuban Missile Crisis and there was a scandal in Canada of the U.S. stationing nuclear missiles on Canadian soil without asking if it was all right with us. In the end, of course it wasn’t. These things were always in the news and they were presented as existential threats. In the time between all this, it seems we’ve mostly been able to ignore it — most people figured it wasn’t as large a problem anymore. But it always has been a threat because the missiles are there. When the Soviet Union broke up, there was another moment when we had to pay attention to it because all of a sudden the triggers for those missiles would fall into the hands of someone that we did not know and what their attitudes would be we didn’t know. So there was another moment of instability, but it settled down once again until last year.

WP: Do you think people are removed from the issue of nuclear warfare today? It seems like people should be so well connected and informed with the popularity of technology, but really there is a perceivable distance among us.

BC: If this is the global village, and you think about what kind of things happen in a village, you’ve got a group of people who can all look each other in the eye and they still kill each other, they still have slaves and they still have to preserve order. Even in tribal communities, there’s some semblance of that. They have customs and certain ways they want things to be done for the benefit of everyone. There’s no reason to assume it’s any less volatile just because we can talk to each other so easily than it would be if we were all living in a Stone Age village somewhere. The main difference there would be that the people in the Stone Age setting would be more likely to realize how much they truly need each other than we are. One of the problems with the social media scenario that we live with now is that it does not foster a sense of need. It fosters a sense of communication on some level, but there’s no sense that your Facebook friends are going to be there for you when the sh*t hits. When my friends that spend a lot of time on Facebook or have a lot of Facebook friends right in their neighborhood get into a crisis, people send them a message. “Oh, sorry to hear you’re in such a crisis!” and they think that actually helps. The distance between that perception and the actual reality is a factor that is more present for us than it would have been for people in a small village. But nonetheless, the human part of it is the same. You can still hate somebody that lives on the other side, or you can still feel victimized by someone who is doing better than you. Those are the real causes of all this stuff. We have a global village that doesn’t address its own issues, and this makes for a more volatile international situation than what would exist without the social media platforms. We know too much now too! It’s too easy to make fun of one another.

WP: There are so many “internet trolls” today who basically thrive off of making fun of another person behind closed doors.

BC: It’s such a hideous development in what could be a truly beautiful thing.

WP: In 1966, you claimed that you felt as if music and art were above politics. Later, you withdrew that statement through the release of the song, “If I Had a Rocket Launcher.” In today’s fragile climate, do you believe that music should be inherently political?

BC: No, actually I don’t. I think that you can do what you want. If you’re somebody that is making art, whether that’s music or painting or anything else, you should do what your gut and your spirit instruct you to do. For me, if I’m going to write a song, the most important thing is that it be a good song no matter what it’s about, because otherwise you’re just adding to the garbage in the world. But if I choose to write a song about a political situation or about anything that is going to have meaning for people in that arena, then I better know what I’m talking about. It better be firsthand and be my experience of a certain topic. That’s where art has power, when it comes from one’s own heart and soul. So if I just decide, “Hmm… I think I’ll write a protest song about Sean Spicer,” well, I don’t know him and I haven’t met him. I see what he stands for and I hate it, and I can write a song out of my own hate, but if I try to get anything beyond that then I’m going to be bullsh*tting. Then I have no power and my work has no power. Therefore, if you’re going to talk about issues, then you better understand those issues as best you can. And be personal with it because it only has its power when it is personal.

WP: You once said that “Fear of poetry on the party of the powerful seems to always have been with us.” Do you believe that poetry is a medium that can still create change in the world through enlightening the powerful?

BC: Well, I don’t know if it was ever a medium that could create change, I’m not sure about that. It might be. What I do know is that it can be a medium for focusing the energy of a group onto a singular thing. If I go to a poetry slam and I hear somebody coming up with a powerful statement about something that feels like it’s coming from a genuine place, then it affects me. I go out onto the street and I go, “Yeah, that was really well said,” and the next thing I see that might relate to that content, I’m going to remember that and it will affect how I act. It’s kind of an uncertain thing, when you throw this stuff out there’s no control over how it will be received. People will always interpret whatever they encounter through their own experiences. So somebody who hears my songs may not hear them the way I imagined they would. You have to allow for that.

WP: Many people must have interpreted your more political music in some interesting ways. Was that frustrating for you?

BC: Well I had to let go of [the way my songs were received] right away, and I learned that very early in the game with the song, “All the Diamonds in the World,” which I wrote out of my own spiritual experience. But later on, I met this guy who felt that that song had saved him from suicide. I had no idea that was going to happen—it never occurred to me in a million years that a song could even do that. Whatever he got out of the song I suppose had some relationship to what I put into it, but I don’t think it was the same [relationship]. On the other hand, I worried a lot about “If I had a Rocket Launcher,” because I didn’t want people to think that I was promoting violence. I didn’t want people to think that I was trying to recruit them to go out and kill Guatemalan soldiers. It was anything but that; it was a cry of frustration, outrage and pain. And most people got that. Even if they didn’t understand the Guatemalan reference, they understood the feeling and I think most people didn’t take it as an evil statement. But there were those who did. A Toronto critic wrote a review that all the copies of that album should be rounded up and melted down. That’s how much he hated that song. It made me not want to do any more interviews with that critic, but people are entitled to their opinion.

The good thing is people are paying attention and the other good thing is that I’m pretty confident no one actually went and shot Guatemalan soldiers. The song was used in some kind of funny and questionable ways. The U.S. Army used it in Panama when they were trying to take down [Manuel] Noriega. The American army forces had him surrounded and they were blasting rock and roll anthems non-stop to keep them from sleeping or wearing down. The people in charge invited all the troops to submit suggestions for a playlist and “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” ended up on the playlist. So Noriega was forced to hear that at deafening volumes. That’s a less positive use of the song than some others, but when I sang that song for the troops in Afghanistan, they cheered. And you know they’re not cheering out of empathy for Guatemalan refugees. They’re cheering because they do have rocket launchers and they want some son of a bitch to die. So it hasn’t been a completely positive experience.

WP: You once claimed that you don’t think the police and the people in the army should be the only people who have guns. Following the recent shooting in Las Vegas, where do you stand on gun regulation? Has your outlook toward that changed in any ways?

BC: I think that the U.S. has a big problem with guns. There’s no question about that. The gun folks will claim things like, “gun control means a good eye and a steady hand,” but if everyone with a gun had a good eye, a steady hand and a functioning brain then there would be no problem because it’s not the gun that does the act, it’s the gun in the hands of someone either with extreme stupidity or a lack of good will. Now, stupidity and ill will are not going to go away from the world, so you have to cover that somehow. The idea that guns are as available as they are to virtually anybody in the U.S., I think is a mistake. I don’t think it should be that easy. At the very least, it should be comparable to driving a car. We have to hope that what happened [in Las Vegas] is not typical of gun crimes to come. Really what you’re talking about as the social phenomenon is not the mass murderer but it’s the four-year-old who gets the gun out of a purse in a supermarket and shoots somebody. It’s the idiot who shoots somebody knocking on their door who is simply looking for help because they’re lost, or the school kids who get ahold of guns. That is the real problem. It’s also hard to find a reasonable voice or a reasoned voice who is addressing the problem. Unfortunately, this country has a hard time having a dialogue about anything these days, and this is one of the hot-button issues that is very hard to have a meaningful dialogue about. You either find people who agree with you or won’t, and there is no middle ground.

It’s a terrible thing. As a social phenomenon, it is really out of control and needs to be reined in. What we all struggle over is the “how?”

WP: Bob Dylan recently won the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. His winning brings forth the question: Can songwriting be viewed as literature?

BC: I think that what I write is like poetry. I’m scared to call it poetry because then I invite comparison with great poets. It just scares me to think that someone might put my name on a page next to Dylan Thomas, T.S. Eliot or even Allen Ginsberg. Maybe in some ways [Ginsberg] is a less scary comparison, because I feel like my stuff is closer in some ways to his in style and spirit, but at the same time I still don’t like the idea of being put into that ballpark. I prefer to think of my words as song lyrics, but other people see them as poetry and call them poetry and some people have done me the honor of paying very close attention to how I write and what I write. I think you want to be careful when asking if music can be literature, because music doesn’t have to have words.

WP: Speaking of music without words, the song “Bone on Bone” from your newest record features four minutes of moody acoustic strumming. When you’re writing music without lyrics, is your process any different?

BC: It’s really quite different from song writing. For me, songwriting starts with the lyrics. I get an idea for a lyric and that idea starts to take shape. Then at some point, there’s enough there to begin thinking about how to put music to the words. With the instrumental pieces, they just come out of exploring on the guitar. There’s the same degree of accidental origin as a song with lyrics, but it comes from different mechanics. When fooling around on the guitar, I’ll stumble on something that could be the basis for an instrumental piece, and then I work on it to try to find more things to add to it so that it can become a finished piece. A piece like “Bone on Bone” has the basic structure of a Jazz tune. The other pieces have a more carefully composed structured.

WP: For someone who has played the guitar for so many years, have you found that you still find new and exciting ways to explore the instrument’s sonic capabilities?

BC: I don’t have the flexibility in my fingers that I had 15 or 20 years ago, but there are still new things on the instrument that I don’t know. It’s just important to keep learning. If you don’t keep learning and exploring, then you’re going to stagnate. And that is with respect to anything at all in life.

WP: The first song on your new record, “States I’m In,” feels like a tale of your experience within American society — how each space you’ve been to has perhaps had its own impact on you.

BC: The song is really a reference to the United States and that’s the play on words there. It’s a really personal song. What I’ve been saying about it is that it’s an encapsulation of a sort of dark night of the soul experience. It’s sort of mythic but it unfolds over the course of the night. The darkness in it is…an exploratory state, but it’s one full of angst. As we said earlier, it’s up to everybody to bring his or her own experience to the music, and that will be true of this song too.

WP: Thank you so much for the time Bruce, and I’m looking forward to seeing you on Nov. 7 at the Calvin Theater. I hope that San Francisco sky clears up soon.

BC: Thanks for the interest, I’m looking forward to being there.

William Plotnick can be reached at [email protected].