When Emma Schonemann felt lonely during her first year in college, she found community service as a source of belonging and joined the Boltwood Project, a student-run service learning program offering enrichment for adults with physical and intellectual disabilities.

“I always knew that I wanted to be involved in some way in the community, I just didn’t know really how yet,” Schonemann said. “Boltwood was a good starting place.”

The Boltwood Project is one of multiple service-learning programs led by the office of Civic Engagement & Service Learning at the University of Massachusetts. Not a college or major, CESL is an academic certificate program for students interested in the intersection of community service and education, with roots tracing back nearly three decades.

When service learning emerged as an academic discipline, former Provost Glen Gordon launched a committee to create service learning classes in 1993.

“That committee was just a group of faculty that would meet that were interested in developing service-learning courses,” CESL Director Joseph Krupczynski said.

Committee members established a fellowship for faculty developing service learning courses. In 2000, the Commonwealth Honors College created an office that offered these courses primarily to honors students, and by 2011, CESL became a standalone office serving all UMass students and continued the work of longtime service-learning programs including Boltwood.

Schonemann, a senior early education major, now carries two bags to the UMass campus on Wednesdays, one containing what she needs for her classes, the other, dubbed her “Boltwood bag,” filled with stickers, markers and construction paper for the weekly “Good’ell Times” program she leads.

As many as six adults join Schonemann and five other student volunteers in the Goodell Hall basement on Wednesday nights. They play games or complete arts and crafts projects while learning about one another’s lives.

“A lot of the times, we’ll make holiday cards,” Schonemann said. “They have a lot of family members that they could give it to. Like Paul, he has three sisters, so he always has to make three cards.”

Paul and the other participants travel from assisted living homes in the Pioneer Valley to join the “Good’ell Times,” and Schonemann communicates with staff at their homes to coordinate activities. She has known Paul since her sophomore year and considers herself close to him.

“Boltwood has given more to me than I have to them,” Schonemann said. “As I started to do it more, I started to learn more and more about ageism and ableism and things that we don’t learn in like high school, and I was totally fascinated … I’m now doing my capstone and thesis on ageism and intergenerational activities.”

After four semesters of CESL classes, Schonemann will graduate in the spring with a service-learning certificate and a new perspective on ableism as she prepares to become a teacher.

“All [CESL] programs are academic focused and credit bearing,” Krupczynski said. “It’s not a volunteerism program, where you kind of come in and volunteer. All the work that we do is connected to some sort of learning.”

Krupczynski, an architecture professor, teaches a class called “Design Engagement,” where he challenges students to consider how social and political movements impact architecture.

“That is the curriculum part of it,” Krupczynski said. “I could teach a class like that, and you’d have a whole series of readings on different aspects of that, and students then would write a paper, do a presentation, and it’d be a really terrific class.”

“What makes the service-learning class unique,” Krupczynski said, “Is that you’re doing all of that, and at the same time, you have a component where we’re actually doing something in a community context.”

Community-based learning is at the core of all CESL classes.

“One of the key things that one needs to unpack right away when we do this kind of work is the saviorism model,” Krupczynski said. “This idea that okay, we’re gonna go and help these poor folks and make their lives better.”

Krupczynski grounds his work in the principle that “nothing about us without us is for us,” a quote hanging in his office alongside a newsclip of the Young Lords Party and an art print from Mexico captioned “ORGANIZACIÓN.”

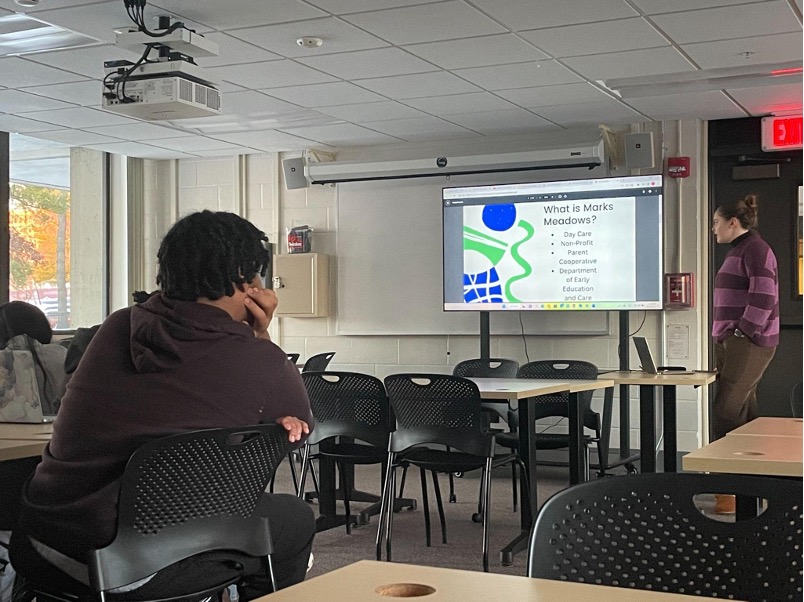

First-year students in the “Impact: Self Awareness, Social Justice & Service” CESL course engage in community-based learning by volunteering weekly at one Pioneer Valley community partner organization of their choice. Students serve food at Amherst Survival Center and Not Bread Alone, teach English to immigrants at the Center for New Americans and provide childcare at the Mark’s Meadow and VELA afterschool programs.

“A lot of our partners, we think about them as educators,” said “Impact” instructor Terrell James, who is pursuing his PHD in anthropology. “They come to this work with that framework as an educator, so they know that they’re there to support our students in learning.”

“Sometimes students are asked very deep, serious questions about their own personal lives … and I think if they didn’t have that community, they wouldn’t be as vulnerable in the class,” James said. “It’s like if you’re making a soup, you always have the broth that’s the base. The RAP is like the broth.”

“We talk about a lot of really serious stuff like wealth inequality and racism and systemic oppression,” said Abi Keefe, a first-year psychology major. “To be able to talk about that stuff, you have to be comfortable with the people you’re around.”

Denora Remy, a first-year psychology major and student of James, meditates before mentoring Amherst Regional Middle School students at the VELA after-school enrichment program, which supports the social and academic development of marginalized youth. Remy helps students complete their homework and assists activities including guitar lessons.

“In class, when we talked about meditation and knowing who you are before you go into a room, I think that’s very important for you to do before you go into your community service site,” Remy said. “Before I walked in there, I was like, ‘I’m already ready, I meditated, I’m ready for these kids to throw anything they want to throw at me.’”

During their end-of-semester reflections, James asked students to identify institutional inequities in the United States that make their community site necessary. Students pointed to wealth inequality and capitalism, white supremacy and gender oppression as reasons their nonprofits were in demand.

Keefe said there is no partisan course requirement for prospective CESL students and encouraged students to take a class on service learning, no matter their views on social justice.

“If you aren’t being actively anti-racist, or you’re not actively anti-capitalist, or you’re not considering yourself a feminist, this is the class that you should take,” Keefe said. “Maybe you’ll come out of it as an anti-racist … or maybe not. But at least now you have a significant more amount of knowledge than you did before to make a more educated decision about your life.”

Civic engagement reshaped Remy and Keefe’s perspective on the state of the country and how they want to approach conversations on current events.

“It’s great for family dinner table arguments,” Keefe said, but she admits she learned more than how to argue. “For the rest of my college career, I have all this information in my mind that … will make me reflect before I say something.”

For Keefe, her understanding of the type of person who performs community service also shifted.

“Taking this class doesn’t automatically make you a good person, and having this class make you go to community service doesn’t make you a good person.” Keefe said. “You have to put in personal work.”

“I think a lot of people go into community service with, ‘I’m doing this cause I’m a good person,’” Keefe added. “Doing community service does not make you a good person … just someone who does community service.”

Sophie Hauck can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @SophieBHauck.