Note: working conditions is a vast topic. A multitude of individual experiences goes into defining what makes a good work environment. Experiences at the workplace can vary based on race, socio-economic status, rank and other factors. However, because the success and functionality of the University is reliant on the employees that run it, the Collegian felt it necessary to report—in a broad scope—how conditions for UMass employees have changed and where employee-University relationship stands currently. This article will briefly cover topics of workplace bullying, the strain COVID-19 put on student employment, and recent changes to job privatization.

Plans for a bright future: University employees

When Kumble Subbaswamy began what would turn into a 12-year chancellorship, he had visions of a bright future for the University of Massachusetts. A Collegian article from 2012 by Katie Landeck noted that Subbaswamy’s plan of action was to “isolate the problems on campus and then fix them.”

Subbaswamy ambitiously saw UMass as becoming one of the top public research universities in the world, let alone the country. The Chancellor also recognized students as the focus and priority of his work. Subbaswamy saw his role as being a “chief advocate” for the University in all aspects.

In 2015, three years into Subbaswamy’s chancellorship, the Collegian wrote about Subbaswamy again. In an article by Nick Canelas, he reflected on Subbaswamy’s predecessor Robert Holub, and describes him as being a “brash character.” Canelas notes that with Holub’s desire for glory “came an arrogance that frustrated many working within UMass” and severed working relationships.

When Subbaswamy took office, his primary goal was to restore relationships that the previous chancellor had broken.

The now outgoing chancellor’s success in raising UMass’s research and educational status is undeniable. In 2015, the Boston Globe reported that 55 percent of UMass students would not graduate in four years, according to Canelas. Now the University’s graduation rate is around 79 percent. Also, UMass currently ranks number 26 for top public schools and 67 in overall national rankings.

The success of any university relies on the staff and faculty that support it — UMass’s impressive rise of rankings is not without the considerations and challenges to working conditions.

Inclusion in the workplace: Then and now

In 2012 — the year Subbaswamy took his seat as chancellor, a group of UMass unions put together a report revealing that a high number of university employees had experienced workplace bullying. The study found that out of all surveyed staff members, two-thirds reported some incident of workplace bullying in the two years prior.

The study also found that most people who reported workplace bullying did not seek help, and out of those who did seek help, 44 percent found the help they received to be dissatisfactory. 64 percent of those surveyed said that being bullied at the workplace increased their stress levels. 16 percent said it was because of their race, ethnicity or gender.

In 2012, the percentage of employees that identified as a person of color was 17 percent of faculty and 15 percent of staff workers, according to the UMass institutional research.

The study also included direct quotes. One unnamed participant said, “Being bullied makes me feel like I am not valued by the organization.” Another said, “My direct supervisor likes to pick on the women in our department and holds back on any promotions on all women.”

“I have lost my trust and confidence in the higher-ups who are causing disruptions in the workplace,” another said.

A commitment to diversifying staff and promising inclusion can contribute vastly to the wellness of a work environment.

Vice Chancellor and Chief Human Resources Director William Brady noted that the University has made significant strides in diversifying its employment demographics. In 2022, Brady said, the percentage of employees who identified as a person of color increased to 24 percent for staff and 26 percent for faculty.

However, as Emmanuel Adero, the deputy chief officer for equity and inclusion noted, diversity statistics are nothing without the promise of inclusion. “The experience of inclusion is subjective and is something you and I either feel or don’t feel,” Adero said in an email to the Collegian. “Diversity can be measured numerically … but inclusion is felt, and it’s up to the people responsible for a community.”

In 2017, the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion was created. “The Chancellor was obviously central to establishing DEI as institutional goals,” Adero said. “Early on, however, I’d say that a lot of our most intensive initiatives in this office were actually driven by the results of the Campus Climate survey of 2016.”

The survey found UMass employees’ overall sense of belonging to be high, but varied significantly based on race, gender identity, sexuality and disability status.

The Office of Equity and Inclusion conducted an extensive workplace climate survey in 2021 which found that overall, the majority of faculty and staff surveyed feel that people care about them and there is a spirit of cooperation in the workplace. However, the survey also found that 33 percent of participants disagreed that they have the resources available to grow and do well in their position and 31 percent disagreed that differences among employees are valued.

Overall, it seems the presence of workplace bullying for most marginalized groups has been on the decline since 2012. However, there were some shortcomings which the study exposed—the recent survey found that 56 percent of staff with disabilities reported that they experience some form of “bullying on the job.”

Over 55 percent of nonbinary individuals recorded they sometimes or often experienced mistreatment at work, and 37 percent of women reported the same.

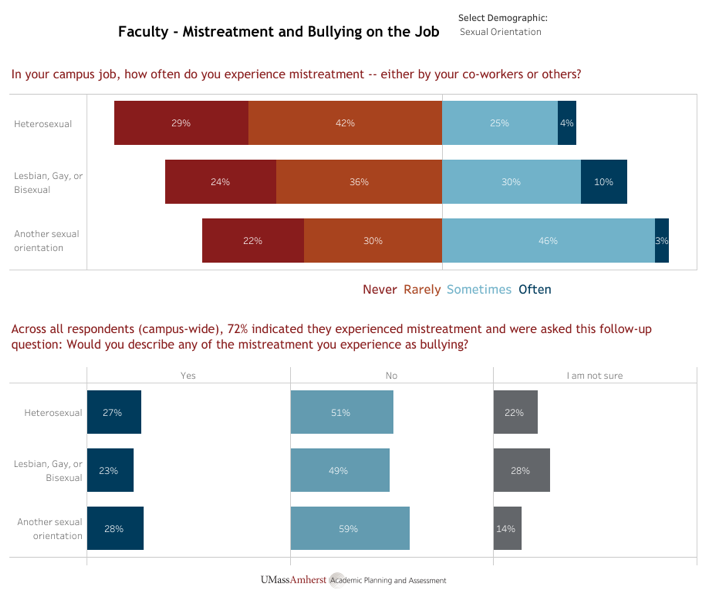

Around 33 percent of all employees of color surveyed reported “sometimes or often” instances of workplace mistreatment. Almost 50 percent of respondents who identified with the “another sexual orientation” column reported the same.

“We intend for the 2021 survey to similarly drive our work over the next years,” Adero said.

Student employment: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UMass Dining Services and the PVTA system

UMass employs 9,212 people across all departments. 55 percent are student employees.

“We have a very large contention of students that work on campus and it’s a large chunk on the payrolls,” Brady said.

Student employees are managed in the same way as full-time staff, except for the understanding that they are students first. “I think that there has always been an attempt to reflect on the needs of the students,” Brady added.

Brady noted that the closing of campus in March 2020 allowed the University to see that for some departments, remote work is just as effective.

“In my division we now have students working remotely … and that’s very different from how we were before the pandemic,” Brady said.

“I think that higher education in general is very conservative around what it means to be an employee here and we almost always had our folks here on campus,” he added.

The Pioneer Valley Transit Association and dining hall system at UMass employs the largest number of students — and these departments had no options for going remote.

UMass dining consistently ranks number one for best national dining and continues to do so even following the strain caused by the pandemic on the food service industry.

Director of Residential Retail Dining Garett DiStefano has been with UMass for 13 years. The functional operation of the dining system at UMass has always relied on student employment. “When we started to re-densify the campus … we did have a significant number of jobs to fill.”

When the dining halls are fully staffed, they have about 1,200 student employees. “Students are our best asset for recruiting, they bring friends in,” he said.

DiStefano noted that generally student employees work in the same dining location for all four years, and typically new hires apply in the spring of their freshman year, after they have already settled into college for a semester.

For many student employees, working at the dining hall becomes more than a job; it can be an addition to their social circle and college experience at UMass. “It’s more than just a job for them, it’s a connection with people,” DiStefano said.

Spring 2021 and fall 2022 was one of the toughest periods of time DiStefano recalled during his time working in this position. “We were really struggling to get students to work with us … We lost a solid year of students who were working with us and helping us to recruit.”

“A lot of people were apprehensive about working,” he added.

In the interview with DiStefano, he noted a university-wide “ladder program” which was instituted about five years ago. The initiative to make internal hiring a priority and provide opportunities for lower ranked employees to move up the ladder.

“The best way that [the University] can recruit is from within … and the best way to do that is by retaining your best people,” DiStefano said.

Every year, the University honors 10 high achieving student employees with the Gerald F. Scanlon Student Employee of the Year award. The award description describes an employee of the year as being someone who completes assigned tasks with high quality, attends shifts regularly, is highly dependable and provides original contribution to the workplace.

Philip Baird had just transferred to UMass when he decided to become a tour guide. “I really was just broke, I had no money and needed a job,” he said. “I like UMass and I feel like I can speak about why to choose UMass over another universities, because I chose UMass over a different school,” he said.

Baird developed a genuine enjoyment in giving tours to prospective students and their families. Now about to graduate as a fifth-year student with a BA in geography—Baird plans to continue his career here at UMass and will work as an Admissions Counselor in the Enrollment Management department.

Baird’s experience as a UMass employee is an example of the “ladder-program” being implemented.

The PVTA system is the second largest student-operated transit service in North America, as Constance Englert, director of UMass transportation services, said in an email to the Collegian.

The PVTA Amherst operation currently employs 180 students, which is fewer than pre-COVID when they employed 220 students.

“Our staffing levels have ebbed and flowed … COVID-19 had made major impacts to our regular cycle of incoming and graduating students, but we are slowly returning to our regular recruitment cycles,” Englert said.

Student staff take on big roles in the operation of the bus system. Daily management, direction and operational supervision is all conducted by student employees.

“We’re all certainly understaffed and always working hard to cover all of the schedules,” Englert said.

The dispatch rate, which is the number of buses operated during bus schedules, has remained high at 99.7 percent despite the system being down 40 employees from usual numbers.

Englert noted that there is “little change” in how “student leaders and co-workers have managed UMTS services since 1969 when we first began.”

The Problem with Privatization: UMass’s relationship with unions through the years

In March 2023, the University announced its plan to privatize over 100 jobs within the Advancement Office of UMass. Vice Chancellor for Advancement Arwen Duffy announced that the jobs would be moved to the UMass Foundation, which was created in 2021.

The University claimed this change was to ensure full compliance with state laws. Labor unions such as the Professional Staff Union and University Staff Association protested outside of the Whitmore Administration Building.

In the 2012 workplace bullying survey, 10 percent of survey participants said that they experience moments of workplace bullying due to their union involvement. UMass has always been a union-heavy institution; therefore, the relationship between the University and unions has always been at the forefront of employee management.

According to the PSU website, 95 percent of professional staff employees at UMass belong to the Union.

In 2002, undergraduate residence assistance and peer mentors set a “legal and organizing precedence” by gaining union recognition after a hard battle with the University.

Former interim Chancellor Marcellette G. Williams published a chronicle in 2002 titled “Why a Union for RAs Makes No Sense,” in which she argued strongly against the formation and recognition for an undergraduate RA union represented under the United Auto Workers. Williams wrote that bargaining with undergraduate student employees would potentially open the door for “financial aid, academic status, student conduct and discipline, and dormitory conditions and regulations” to be negotiated.

She added that a RA unionization would “severely impair the University’s ability to function as an educational institution … we believe that the unionization of undergraduate students is incompatible with our responsibility to provide a high-quality educational experience.”

Williams argued that it is “dangerous” to characterize the experience of being an RA, by reducing it to an employment position.

In the same essay, Williams goes on to admit the emotional toll and tremendous workload it takes to assume an RA position, writing that “dealing with negative student behavior is not pleasant,” which suggests a need for worker representation.

Thomas Corcoran and Cai Barias of the Graduate Employee Organization said in a statement to the Collegian that over the last decade it has become increasingly more difficult for graduate students to “live and thrive during their time at UMass.”

Corcoran and Barias noted that although there have been recent campus protests, graduate students have always experienced challenges with privatization, such as housing and childcare needs.

“This practice forces graduate students to go to the market for these needs,” they said. They added that over the last decade “the University has resisted the inclusion of graduate fellows within the bargaining unit,” which has refused them benefits such as healthcare waivers.

When placed in comparison with Williams’ argument, it seems that despite the University’s wide acceptance of union organizations and the administration’s belief in “good faith bargaining” as Chancellor Subbaswamy noted in a recent interview with the Collegian, there has always been slight resistance to union mobility.

In the same interview, Subbaswamy brought up that the union’s point of view in negotiations will “always be singular,” as they are concerned with the needs of the workers, whereas the administration is concerned with the whole of the campus community.

However, as protestors said in a recent Collegian article, employees are protesting UMass’s recent decision to privatize because they are the backbone of UMass.

Grace Lee can be reached at [email protected] and followed on twitter @Grace_Lee.

Ed Cutting, Ed. D. • Jul 9, 2023 at 8:15 pm

Reading this I wish to vomit — voting for GEO was the worst thing I did at UMass.

Before GEO, every graduate student had an assistantship — a tuition waiver and some money. What GEO did was eliminate 2/3 of the tuition waivers, graduate students were still working (for less money than before) and no tuition waiver.

They think those with tuition waivers have it tough — try being a grad student without one….